MEXICO CITY — Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), is regularly portrayed as an authoritarian leader with dictatorial tendencies who is eroding the country’s democratic institutions. A charming demagogue whose supporters mindlessly follow him, taken in by his populist rhetoric.

As a Mexican scholar and journalist, I have also been very critical of AMLO. He is a leader with populist impulses who commonly resorts to publicly bashing his adversaries, regardless of whether their criticism is substantiated. His harsh austerity measures created needless suffering during the pandemic and the aftermath of Hurricane Otis, and have degraded effective governmental systems to the point that military forces are now responsible for matters that would normally require civilian leadership.

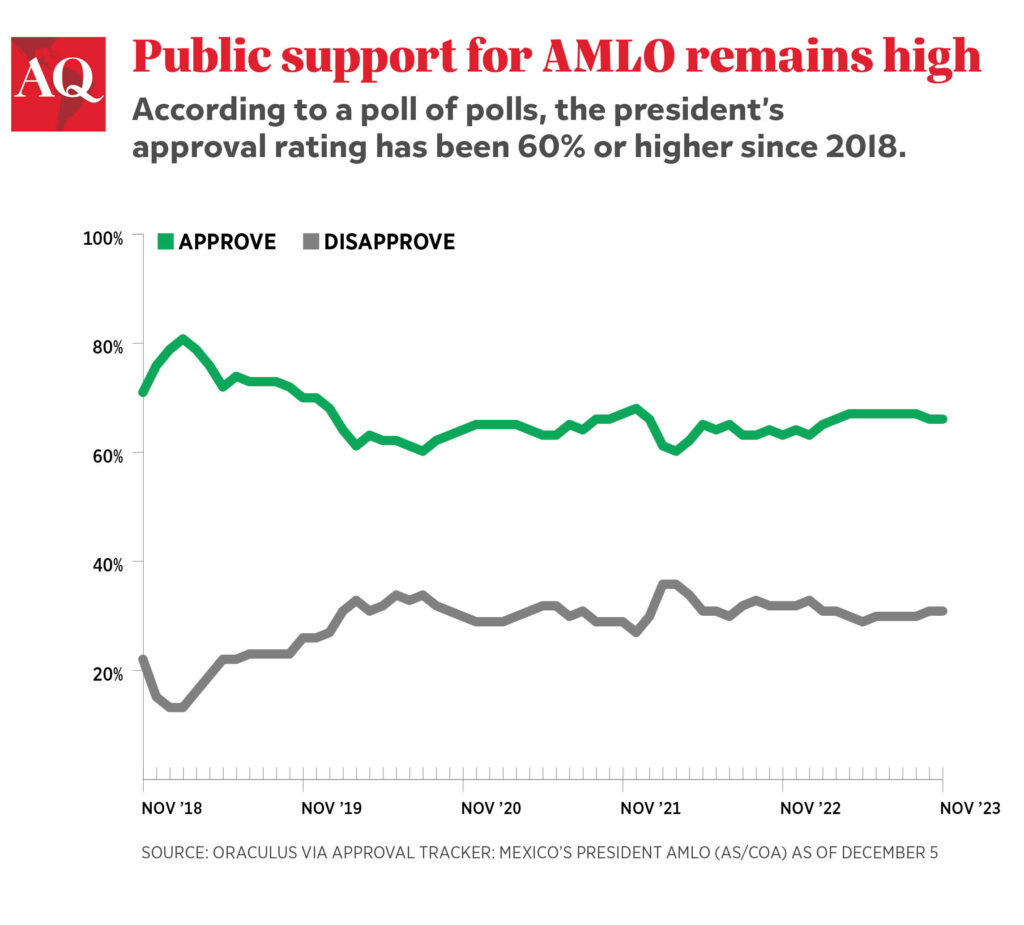

Despite this, such a flawed leader enjoys a very high level of support among Mexicans—around 66% in one average of polls. Polls also suggest that AMLO’s loyal successor, Claudia Sheinbaum, the former mayor of Mexico City, will easily win the 2024 Mexican presidential election. AMLO’s party, Morena, is also the favorite to win most of the governor races.

As of today, a shockingly common explanation for why this is happening is that AMLO has fooled Mexicans. Voters blindly follow him, this explanation goes, because they like him beyond any rational reason.

I do not think this is true. To treat AMLO’s popularity as some kind of hollow scam is to miss out on a historically significant moment in Mexico’s young democracy. There is much more going on here.

Indeed, AMLO’s government has delivered important domestic policy accomplishments that have favored the poor. He increased the minimum wage by 85% above inflation, and enacted labor reforms that reinforced a new generation of democratic and autonomous unions. As a result, wages, as measured by per-capita labor income, have reached an all-time high on record for Mexico.

A focus on the working class

AMLO has invested a significant amount of public funding in development initiatives, like an interoceanic corridor and a tourist train, to expand employment and commercial opportunities in communities that have been investment-hungry for decades. Internationally, the Tren Maya has been criticized for its environmental impact, but a survey from October 2021 (the only public survey focused on the region) found that 87% of locals approve of its construction because they want jobs and economic opportunities. The IMF expects the Mexican economy to grow a healthy 3.2% in 2023, and according to Mexico’s Central Bank the poorer states of the south are growing more than the rest of the country.

Perhaps more significantly, the number of families receiving social assistance has steadily increased during his mandate. Today, 14 million families receive cash transfers, and the average payment has increased by 55% adjusted for inflation. These transfers take 3.5 million people out of poverty, a 52% increase over previous administrations.

His government is the most visible opponent of previous administrations that failed to deliver results to most of the population while enriching a golden upper class. By the time AMLO took office, 88% of Mexico’s citizens believed that the government primarily served the elites, and by some measures, the country was the fourth-most unequal in the world.

Unlike prior technocratic elite administrations, AMLO wields power in ways that are widely perceived as more real, democratic, and closer to the people. He takes the bus, stops at random convenience shops to get his own food, and speaks vernacular Spanish. At state banquets, he offers rural Mexican dishes like tamales, and he conducts daily news conferences in which he repeatedly emphasizes the viciousness of Mexico’s economic elites. For decades, he has visited little communities that were previously uninteresting to federal officials. People in those communities remember him as one of their few genuine encounters with the Mexican state.

As a result, AMLO has boosted Mexicans’ perception of their democracy. During his first years in office, the proportion of Mexicans who trust the federal government approximately doubled, and their satisfaction with democracy did as well, according to the respected regional pollster Latinobarómetro. And although security remains a major concern for Mexicans, homicide rates have fallen slightly from 28 to 25 per 100,000 from 2018 to 2022, and citizens report feeling safer than at any point in more than a decade.

A renewed faith in the government and its institutions has emerged. The public perception that the federal government is not or is only rarely corrupt has tripled. According to a May 2022 survey, two-thirds of Mexicans want the next administration to continue his work.

Of course, there are plenty of reasons to criticize AMLO. He has failed to enact much-needed fiscal reforms, such as raising taxes on the wealthiest, and has failed to build an industrial policy to promote economic development. Mexico’s health-care system has deteriorated due to chronic underfunding, harming the lives of millions of families. All these are legitimate critiques.

Furthermore, the question remains as to whether AMLO will use his charisma and authority to undermine electoral institutions and weaken the chances of the opposition parties winning. In my opinion, this threat is greatly overstated. The question must be seen in context. There are not significant signs of democratic breakdown in Mexico.

Mexico’s electoral institutions are solid. Since AMLO took office, there have been numerous elections, and both domestic and foreign observers have generally regarded them as being fair and clean. AMLO could not get a supermajority to reform the National Electoral Institute and reduce its budget, even if 66% of Mexicans were in favor of it. The reform was uncritically covered as an attempt to destroy democracy, when in reality, reforming the institute would affect AMLO’s party as much as it would others. Of course, there are plenty of imaginary scenarios where AMLO designs and implements catastrophic electoral reforms. Yet, none of those scenarios have materialized.

His party has recognized electoral failures, including losing its congressional supermajority, multiple key districts in Mexico City, the powerful state of Nuevo León, and six other gubernatorial races. There is little doubt that the next presidential election will be free and fair and that AMLO will leave office as planned in 2024.

The media remains free to be highly critical of AMLO’s government. If anything, supporters of AMLO may be underrepresented in the media, rather than the other way around. His opponents are free to organize and demonstrate, and they have done it with great success. There hasn’t been a single politician arrested for speaking out against his administration.

A polarized Mexico

The question is why the minority point of view that AMLO has offered nothing to his voters has become the dominant account for understanding contemporary Mexico.

This, in my opinion, has a lot to do with the types of Mexicans who get to speak and who the world press pays attention to. International commentators frequently rely on the perspectives of Mexicans who can speak English, hold degrees from U.S. universities, or work in corporate-funded think tanks to construct their own perception of Mexican reality. This method breeds a significant bias in a highly unequal society like Mexico, where the potential to study other languages and create a broad international network is limited to those at the top of the wealth distribution.

This is especially problematic given that upper-income earners are the primary source of support for opposing parties and form the base of opposition to Morena. Opposition supporters are well aware of their outsized influence outside of Mexico and have expended much effort in arranging private contacts with international media, inviting them to political events, and explaining Mexican politics from their own point of view.

Amid the polarizing opinions surrounding AMLO’s leadership, one fact remains: His government serves as a symbol of democratic governance for a majority of Mexicans, as well as significant advancements in the quality of life of millions of Mexican families. That may not be enough to meet some definitions of a true democracy; but for many Mexicans, it represents a much better government than they were accustomed to having.

__

Ríos is a Mexican scholar and author specialized in inequality and social policy. She holds a Ph.D. in government from Harvard University.