This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on cybersecurity

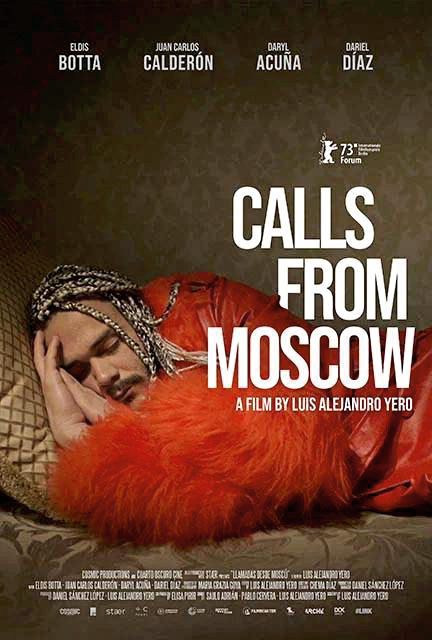

For the protagonists of Luis Alejandro Yero’s Calls from Moscow, the Russian capital was a place of intense silence and isolation on the eve of the invasion of Ukraine: almost a ghost town.

“Here nothing happens,” says one of the four Cubans, recently exiled queer men, who form the focus of this bold first feature film, shot just weeks before the start of the war.

Undocumented, unable to speak Russian and facing the brunt of the Kremlin’s anti-LGBTQ laws, the men’s decision to abandon their homes lays bare Cubans’ desperate search for a more promising future.

Dariel, Daryl, Juan Carlos and Eldis live in spare, furnished apartments high enough above the ground to block out any noise from the city below. Yero trails the daily experiences of his uprooted compatriots as they pass their days between precarious work — construction gigs, call center stints — and seemingly uninterrupted phone use. They lip-sync on TikTok and keep up with the news back home. They also talk: Conversations with bosses, clients and, of course, loved ones fill the air of an otherwise silent Moscow.

Wide shots of huge Soviet-era plazas, snowy train tracks and concrete parking lots, all devoid of people, contrast with a Caribbean Spanish typically reminiscent of party and dance. On the phone, the men pass through waves of intimacy, nostalgia and dejection. “Of course I’m not happy,” Juan Carlos tells Yero. “But it was tougher to live in Cuba, unfortunately.” At least from Russia, he can help his mother, brother and other close family “in one way or another.”

Calls from Moscow (Llamadas desde Moscú)

Directed by Luis Alejandro Yero

Screenplay by Luis Alejandro Yero

Distributed by Cosmic Productions and

Cuarto Oscuro Cine

Starring Dariel Díaz,

Daryl Acuña, Juan Carlos

Calderón and Eldis Botta

Cuba, Germany and Norway

The degree of misery in Cuba would be hard to overstate. In the summer of 2021, persistent food and medicine shortages led to the largest anti-government street protests since the 1990s. According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection data, more than 224,000 Cubans — nearly 2% of the country’s population — migrated to the United States in 2022 alone. News outlets worldwide qualified the exodus as the largest “since Fidel Castro rose to power.” This year might even break the record again, as roughly 135,000 Cubans have already crossed the U.S. border.

The war in Ukraine only intensified the island’s problems. High gasoline and diesel prices have contributed to more blackouts, and the tourism industry, once heavily reliant on Russians, has continued to drop from pre-pandemic levels. Yet the Cubans in Calls from Moscow, though geographically closer to the conflict than their family and friends, seem oblivious to its cascading consequences. “Everything is normal. The streets are quiet,” Juan Carlos explains. “In the beginning, the youth demonstrated” in the streets, but the “police [kicked] the shit out of them, took some prisoners, and that was finished.” In deference to Russia, the Cuban government — previously given to friendly relations with Ukraine — has tried to stifle any bad press connected to the war. But the irony of an anti-imperialist country supporting the annexation of sovereign land can be lost on no one.

Was leaving home ultimately worth it? This question suggests itself again and again throughout Yero’s Calls from Moscow. The four men traded great material lack for a grueling semblance of security. They moved from one single-party authoritarian state to another — and in the process, they gave up boundless sunshine for endless snow. Perhaps most painfully, they compromised deep, personal relationships and replaced them with incomparably poorer digital counterparts. “Cuba is the Russians’ Hawaii,” Dariel jokes. Yet a tropical paradise never seemed less appealing.

—

Alvarado is a writer and former assistant editor at The Atlantic