This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on cybersecurity

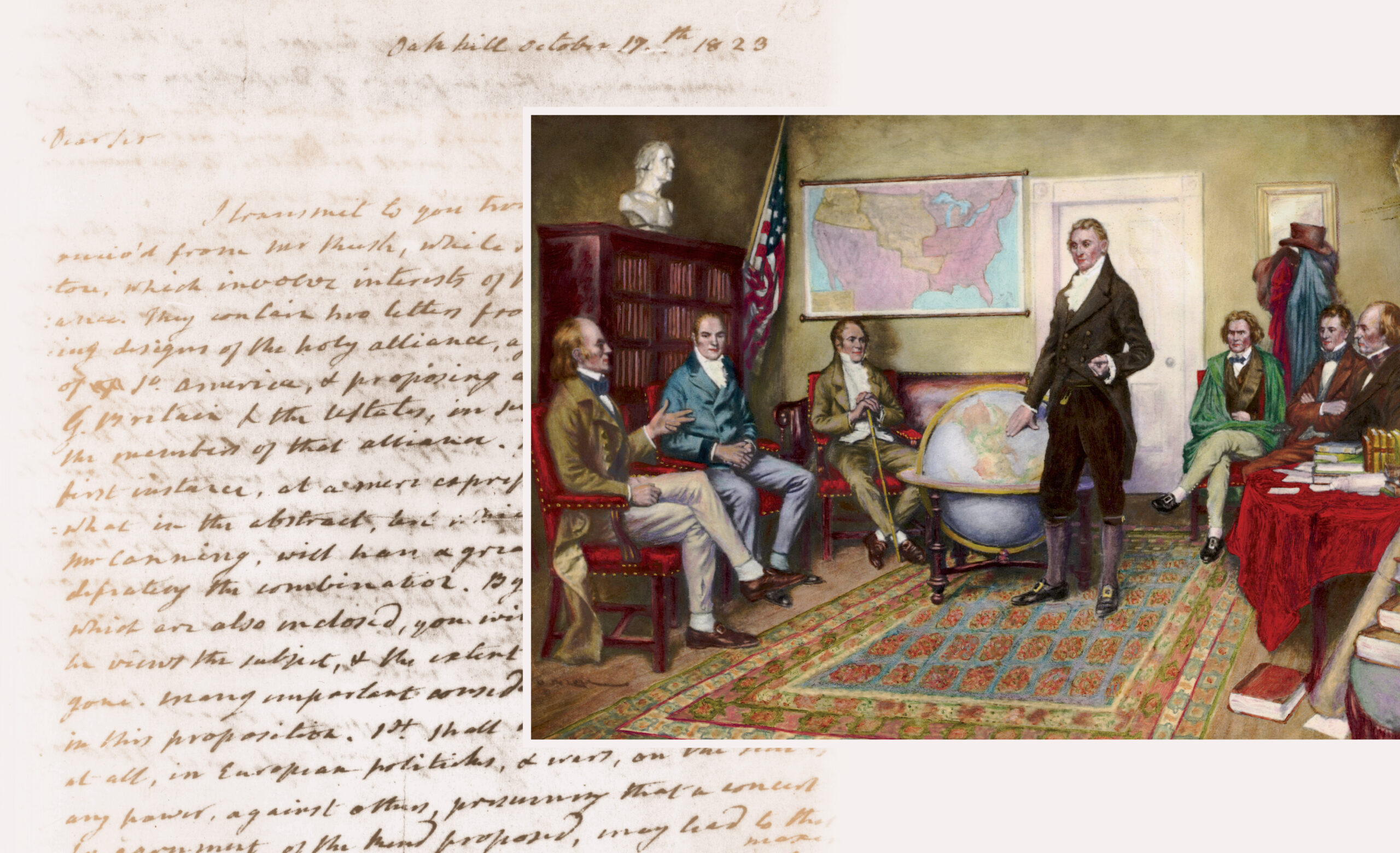

The year was 1823 and the newly independent Latin American republics were under threat. Despite winning diplomatic recognition from the United States, they were not yet safe from possible reconquest by their former European masters. This risk was more than theoretical: The Spanish monarchy was stronger than ever, buoyed by the Holy Alliance of Russia, Prussia and Austria—which helped it stomp out a short-lived constitutional government in Spain in 1823.

The U.S. was worried about Europe, too. Russia was laying claim to Oregon. If the czar and the Holy Alliance could make gains in the New World, the United States could say goodbye to its territorial ambitions for the Pacific Coast, and Latin America could once again fall under the control of imperial Spain—or even predatory France.

At this point, Britain stepped in to make an offer. As a constitutional monarchy, Great Britain had little patience for the absolutism of the Holy Alliance. Even though the British had recently torched the White House during the War of 1812, they approached the James Monroe administration (1817-24) with a proposal to devise a joint declaration against feared interference by the Holy Alliance in the Western Hemisphere. At the time, Great Britain was the preeminent global power, while the United States was little more than a “second-ring show in the high-strung Atlantic circus,” in the words of historian Caitlin Fitz.

Monroe wanted to cooperate with Great Britain. But his more wary secretary of state, John Quincy Adams, ultimately won out. Adams argued that going alone would allow the United States to raise its own credibility as a regional power while avoiding appearing to be a mere lackey of Great Britain. As he wrote to his boss, “It would be more candid as well as more dignified to avow our principles explicitly to Russia and France, than to come in as a cockboat in the wake of the British man-of-war.”

The Monroe Doctrine was the result. Presented to Congress on December 2, 1823, it was a sweeping, bold declaration calling for a hemisphere free of European interference. It pledged U.S. nonintervention in the Old World and affirmed the United States would view European attacks on its hemispheric neighbors as aggression against itself.

In making this announcement, the United States was unilaterally telling its European counterparts that Washington now considered the Western Hemisphere what came to be called its strategic “backyard.” But there was a second—these days often overlooked—tenet of the Monroe Doctrine: an emphasis on republicanism, as opposed to monarchical forms of government in the region (although the U.S. did acknowledge the independence of Brazil, headed by Emperor Pedro I, in 1824).

The doctrine represented the beginnings of the United States’ often proprietary relationship with Latin America. But it’s worth noting that at the time of its announcement, the Monroe Doctrine was more of a symbolic display than one showcasing military might. The U.S. lacked the ability to enforce Monroe’s stated goals. Despite the fierce reputation the doctrine would gain in future decades and centuries, the pronouncement did not prevent European moves violating Monroe’s warning—such as the British annexation, in 1833, of the Falkland Islands (which Argentina refers to as the Malvinas), Spain’s reassertion of colonial control in Santo Domingo (today’s Dominican Republic) in 1861, or, most famously, Napoleon III’s bold gambit to establish a French puppet regime in Mexico during the U.S. Civil War. Until very late in the 19th century the United States was busy becoming the master of its own continental territory, focusing on its westward expansion to the Pacific Coast.

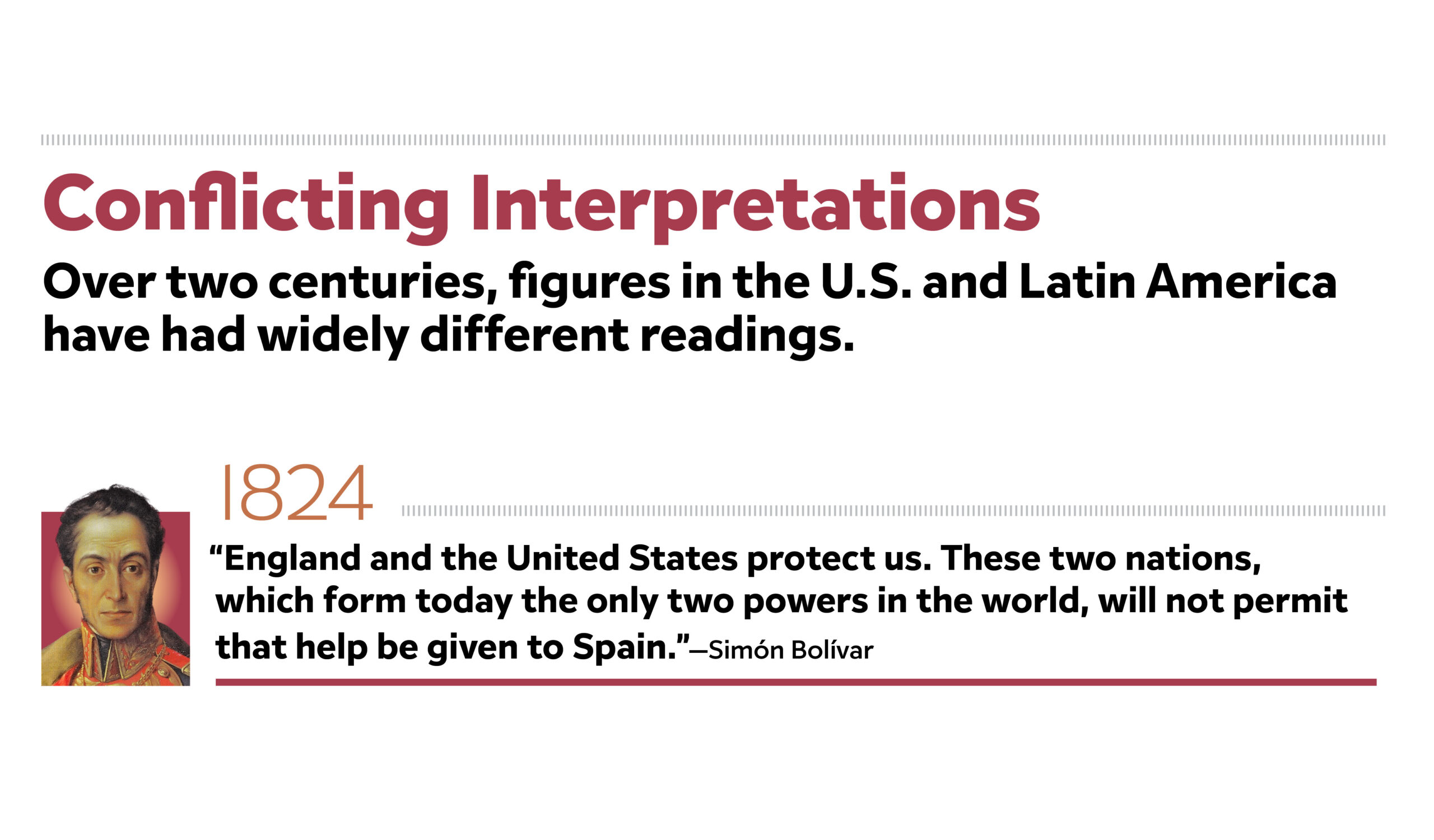

From today’s perspective, it may come as a surprise that many Latin Americans were supportive of Monroe’s defiant declaration bolstering their precarious independence. Colombian Vice President Francisco de Paula Santander described how “this policy, consolatory to human nature, would secure to Colombia a powerful ally should its independence and liberty be menaced by the Allied powers.” Simón Bolívar himself wrote that “England and the United States protect us. These two nations, which form today the only two powers in the world, will not permit that help be given to Spain.” And both Chile and Argentina expressed gratitude to the United States for positioning them beyond the reach of Europe.

The doctrine evolves

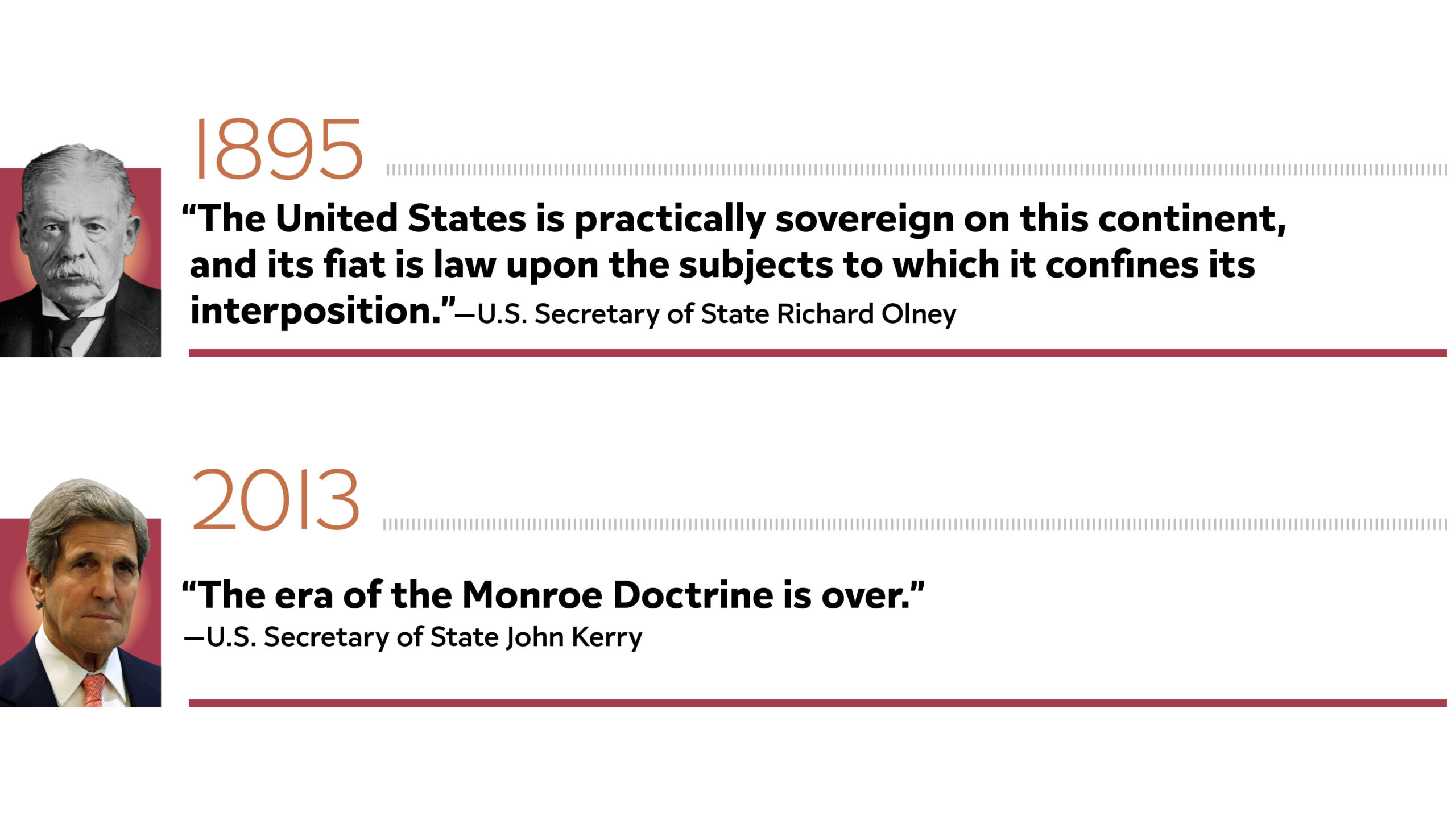

At the turn of the 20th century, European meddling prompted a tweak to the doctrine’s original focus on protecting independence and democracy. In 1902, British, Italian and German gunboats stalked the Venezuelan coast after Caracas ceased paying its foreign debts. This helped prompt President Theodore Roosevelt’s (1901-09) sharp announcement in 1904 that the United States had the right and responsibility as an “international police power” to curb “chronic wrongdoing”—that is, “flagrant cases” of fiscal insolvency and civil unrest in the region.

While the original doctrine was about global powers staying out of Latin American affairs, now Washington—far more global a power in 1904 than 1823—was now proclaiming its right to go in. Over the next two decades, American troops landed in the Dominican Republic, Haiti and Nicaragua, among other countries. The gloves were off.

But in the 1930s and into the World War II era, U.S. policy toward the region took another pivot—and so does our understanding of the Monroe Doctrine’s legacy. President Franklin Roosevelt embraced consultation and cooperation over gunboats and U.S. marines with his Good Neighbor Policy, accepting the principle of non-intervention at the Montevideo Conference of 1933.

The creation of the Rio Pact in 1947 appeared to make the Monroe Doctrine multilateral, transferring the responsibility for defense from the United States to all 19 signatories. With the ensuing creation of the Organization of American States in 1948, Teddy Roosevelt’s pugilistic version of the Monroe Doctrine would often seem obsolete in ensuing years. The John F. Kennedy administration invoked the Rio Pact, not the Monroe Doctrine, during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. Similarly, President Johnson’s major policy speech outlining intervention in the Dominican Republic in 1965 also omitted any reference to the Monroe Doctrine.

A confusing legacy

Even as the Monroe Doctrine receded from prominence in official U.S. policy, it gained ground during the fraught Cold War as a catchphrase employed in both liberal and conservative accounts of U.S. regional policy. Legions of liberal critics in the U.S., and those in countries on the receiving end of perceived yanqui empire, equated the doctrine with heavy-handed, paternalistic and even racist U.S. policy in the hemisphere.

As international communism became the new enemy and violator of the Monroe Doctrine, unilateral intervention by the U.S. was the response. In a period marked by both the perception and the reality of U.S. involvement in coups, CIA intrigue and botched military interventions, the doctrine was understood by many in the U.S. and Latin America alike as a rationale for such action. Even if the doctrine was not always officially invoked during the Cold War, actions are louder than words. The Pan-American defense doctrine was relegated to a back seat as the United States took the fight against international communism into its own hands.

Over the years, many have pronounced the Monroe Doctrine dead. Writing in the late 1990s, diplomatic historian Gaddis Smith wrote that the end of the Cold War marked the end of the Monroe Doctrine. Others have argued that it perished with the multilateralism in the lead-up to and after World War II.

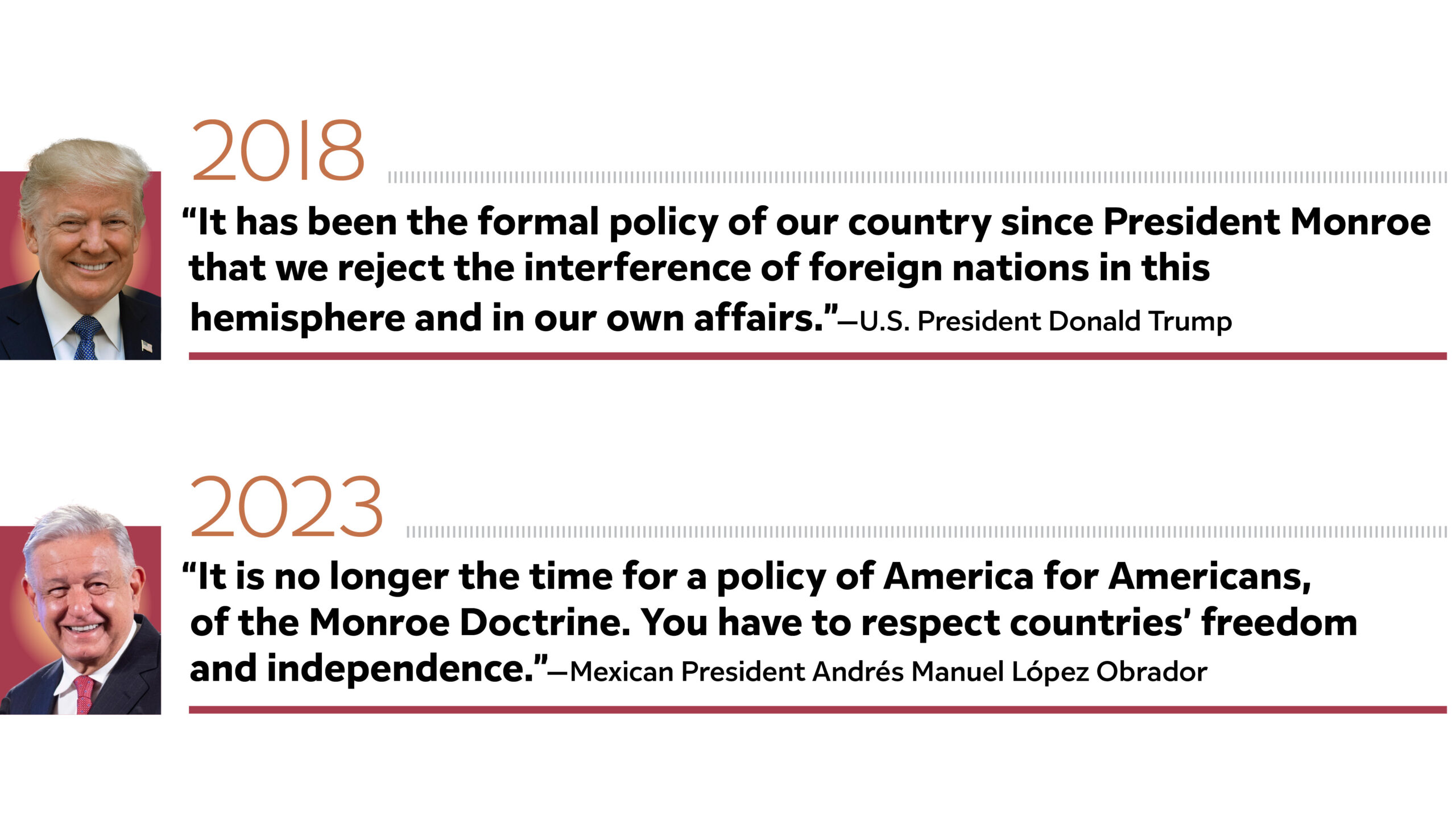

But the confusion has not ceased: Well into the 21st century, policymakers and politicians continue to invoke what is now an unhelpful, even counterproductive term. On the American right, the Monroe Doctrine is shorthand for an unapologetically hawkish approach to the U.S. sphere of influence, one that sees non-hemispheric activity, whether from Germany in the early 1900s, to Russia and China today, as axiomatically malevolent and requiring a stern U.S. response. In this perspective, the doctrine is a more pragmatic, realpolitik reflection of relative power dynamics, as opposed to any specific endorsement of unilateral regime change.

The problem is that the Monroe Doctrine has been overused and misunderstood to the point of meaninglessness; it is one of those phrases, like globalization or neoliberalism, that means all things to all people. Perceived moves by Beijing in the region? Nicolás Maduro’s regime cozying up to Moscow? Conservatives reflexively howl that the Monroe Doctrine has been breached. Liberals criticize ever-abiding U.S. imperialism. The result is an overriding legacy of confusion.

Perhaps rather than a binary focus—asking whether the doctrine is obsolete, or alive and well—it is more helpful to ask which version of the doctrine will mark the century to come. Will it represent new emphasis on supporting democracy? Or will policy revert to the unilateral heavy-handedness of the turn of the 20th century?

The United States will always view its near abroad differently from other parts of the world. But that’s not to say that the U.S. has the ability or desire to unilaterally intervene in the hemisphere the way it did a century ago. Today, Latin American countries have agency and strength that they lacked in 1823. At the same time, most Latin Americans now view the doctrine as synonymous with U.S. unilateralism. In this sense, the doctrine is at once irrelevant, confusing and potentially damaging to U.S. relations with the region.

The changing nature of hemispheric dynamics have left the Monroe Doctrine behind: The best thing that could happen to its legacy is for it to recede into the past.

__

This essay is adapted from the authors’ recent book “Our Hemisphere”?: The United States in Latin America, 1776 to the 21st Century, available from Yale University Press.