This article is part of AQ’s special report on Latin American mayors.

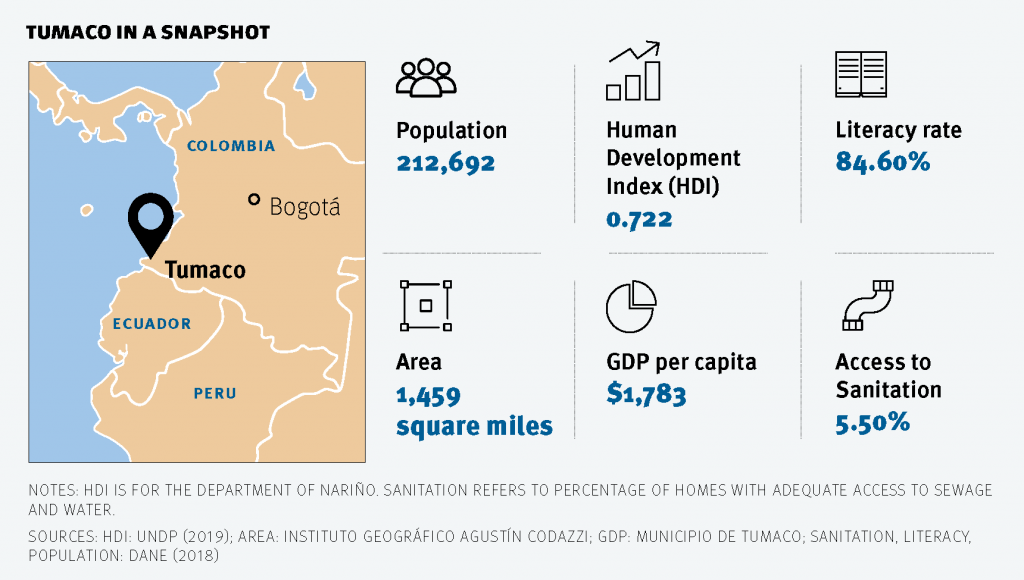

BOGOTÁ – María Emilsen Angulo has an unenviable job. She is mayor of Tumaco, one of the poorest and most violent municipalities in Colombia. In this small port city along the Pacific coast near the border with Ecuador, half of the residents are unemployed. The homicide rate, 154 per 100,000, is four times the national average, and there is a shortage of courts, schools and basic infrastructure such as sewage and water supply systems.

But “coca is my biggest headache,” Angulo told AQ, referring to the plant used to make cocaine. “People here see it as their only way to make a living.”

Tumaco is one of the world’s largest cocaine-producing areas, after the FARC introduced the crop there toward the end of Colombia’s 52-year conflict. According to Angulo, 80% of the families living in the rural parts of town cultivate the crop, which now covers close to 25,000 acres – more than during the conflict. After the FARC disarmed in 2017, other armed groups started fighting one another for control of the drug business, with civilians caught in the middle.

Against this dire backdrop, Angulo, just 37 and the first woman in her job, has stood up to powerful organized criminal groups. She has pushed the police to monitor certain areas and offered cash rewards to anyone who will turn in murderers. Criminals responded by threatening her, and police recently discovered a plot to kidnap her father. Now she and her entire family cannot travel anywhere without bodyguards and bulletproof vehicles. Her daughter rarely leaves the house.

Thinking long term, Angulo said her best option to fight crime is to prevent child recruitment into armed gangs. She has hired soccer players, dancers and ultimate frisbee coaches to keep children in poor neighborhoods away from the influence of criminals. Angulo knows her four-year term is not enough to bring about the changes the city desperately needs, but said small policies like this can make a difference over time.

Angulo had been elected mayor in 2015, but a year into her term a court annulled her election, ruling her husband’s job at Tumaco’s public hospital a conflict. Her successor immediately abandoned her most important project: the construction of a permanent branch of the State University of Nariño to host up to 1,000 students. But Angulo persisted. She was elected again in 2019 – her husband was no longer working for the city – and revived the university project, which she aims to complete by December 2021.

Angulo took office for the second time in 2020 – just as the pandemic hit. Tumaco wasn’t ready for it: The town had no ambulances, intensive care units (ICUs), oxygen tanks or ventilators. Most tumaqueños work informally, and few followed social distancing measures. The virus spread with ease. By July 2020, Tumaco had one of Colombia’s highest infection rates.

In response, Angulo reworked the budget, diverting petroleum royalty funds to repair Tumaco’s single hospital, set up makeshift tent hospitals, and buy one ambulance while convincing private companies to buy four more. The national government provided 15 ICU beds.

In early July, the city’s COVID infection rate remained above the national average. Nevertheless, Angulo told AQ that “if we compare Tumaco’s health care before the pandemic with what we have today, we can say it has drastically improved.”

The first woman in her family to graduate from university, Angulo has been immersed in politics since she was 11 years old, when she started to follow her father, himself a community organizer and budding politician. Soon she was the one giving speeches at her father’s events.

Angulo’s experience and connections in local politics have helped her start repairing Tumaco’s long-strained relationship with Bogotá. Believing Tumaco can be a tourist destination, she started to clean up the city’s beaches, most of which are overrun by garbage, and convinced the national government’s tourism agency to help rebuild the waterfront. Other projects include new hiking trails and an alliance with groups of women to lead kayak tours through mangrove wetlands.

During the massive anti-government protests that convulsed Colombia starting in late April, Tumaco also had its streets blocked by communities that felt left out of the peace deal and who rely on coca for a living. But in Tumaco, the mayor did not send riot police, as authorities did in other parts of the country. Rather, Angulo invited protesters to talk.

Angulo’s working relationship with the national government helped her again, and she was able to bring a minister to the negotiating table, where an agreement was reached to jointly design ways for the national government to invest more in Tumaco.

This dialogue spared Tumaco, one of the most violent cities in Colombia, from the violence that engulfed other parts of the country. “The protesters didn’t throw a single rock in Tumaco,” said Angulo.

—

Palau is a journalist based in Bogotá, Colombia. Follow her on Twitter at @mariana_palau