Gustavo Petro was never favored to become Colombia’s president in 2018. Arguably too far left for the country at that time, Petro barely sneaked into the second round against Iván Duque, to whom he lost by 12%. The big question of 2022 is whether Petro—and Colombia itself—have changed enough for the result to be different this time.

It certainly seems like a different Colombia. In the last four years, Duque’s approval ratings have fallen from around 55% on taking office to roughly 20% today. Persistent and sometimes violent protests sparked by his tax reform efforts were exacerbated by a severe, at times lethal crackdown by police. Jobs lost to COVID-19 have only partially recovered, with unemployment still above 12% as of February. According to an Invamer poll, 85% of Colombians now think the country is moving in the wrong direction.

“The economic and social situation is much, much more complicated,” Juan Gabriel Gómez, a professor at the National University in Bogotá, told AQ. “(In 2018) Colombians felt they had started on a new path, a chance to fix long-term problems … but now in 2022 those expectations have been totally frustrated.”

With his lead in polls now tightening, the question of whether and how Petro has evolved is more complex. The 62-year-old senator and former mayor of Bogotá has seemingly tried to calm fears of an authoritarian streak by softening aspects of his platform. In an interview with El Pais last year, he said that Colombia needed “democracy and peace,” not socialism. He’s dropped entirely a proposal floated during the last campaign for a constitutional referendum. Similar to in 2018, he has signed a pledge not to expropriate “anything or from anyone.”

Petro has also been far more aggressive in forging alliances with traditional establishment politicians than he was four years ago. While outreach efforts to the centrist Liberal Party were complicated by his running mate Francia Márquez’s criticism of a party spokesman (and former president), some Liberal politicians have given Petro their backing all the same. Other potential alliances, including with evangelical groups, have even come at the cost of alienating parts of Petro’s base.

“Petro has opened the door to traditional figures who had very little access to public resources under Duque,” said Gómez. “A lot of this looks like pure political opportunism. If these politicians had found a better offer elsewhere, they likely would have followed it.”

Ahead of the first round of voting on May 29, however, it’s clear that in many respects this is the same Gustavo Petro as before, the one who routinely aimed personal barbs at political opponents and the press and appeared to improvise major public policy proposals.

Last month, Petro referred in a tweet to an opinion columnist who questioned his pension plan as a “neo-Nazi.” In 2020, he said he would encourage civil disobedience, including by refusing to pay for public services, in response to Duque’s “illegitimate” government. He also recently spoke to the need for a broad “social pardon” after his brother’s visit to a former mayor and congressman in jail on corruption charges became public. Petro clarified that he was not referring to legally pardoning criminals, white-collar or otherwise, but polls suggest the episode could nonetheless hurt him at the ballot box.

Context matters. Colombia has never elected a leftist president, and decades of armed conflict with Marxist-inspired guerrillas have left many voters skeptical about big changes offered by leftist politicians. But some of Petro’s ideas, and the way he communicates them, have inspired doubts about his commitment to political and legal norms.

Petro says he would stop current fracking pilot projects and end new exploration for oil, which accounts for around half of Colombian exports. He wants to raise taxes on Colombia’s 4,000 richest people and move money currently in private pensions to a public system, which critics claim would amount to the expropriation of private wealth.

“It’s evident that there’s a problem in Colombia’s pension system,” said Mauricio Reina, a political commentator and researcher at Fedesarrollo, a think tank. “But his plan doesn’t establish a before and after, or respect vested rights.”

In an interview with Blu Radio, Petro said his first act as president would be to implement a state of emergency to address hunger. Almost 16 million people in Colombia live on two meals or fewer per day, according to the National Association of Foodbanks. Petro said in the interview that the state of emergency would be limited only to the issue of food security and circumscribed by Congress and the courts.

The Duque administration itself used emergency powers to take steps against COVID-19 that included an acceleration of controversial “VAT-free days.” But given Petro’s temperament and history—including past membership in the M-19 guerrilla group—his comments reinforced concerns among observers that he might try to bypass traditional checks and balances if he doesn’t get his way.

On April 21, Petro tweeted a research note from J.P. Morgan saying it proved the bank did not see any cause for “alarm or mistrust” with his policies. But while the note did suggest that some of Petro’s economic proposals, including on pensions and oil exploration, may not be as radical as opponents claim, it also highlighted the possibility of “institutional tension to come should Petro find that his agenda is struggling to advance.”

“Petro has the same arrogance as ever. He is convinced that he has the answer for everything,” said Gómez. “There is a fear among some Colombians that, after encouraging supporters into the street or clashing with Congress, he might do something like (President Nayib) Bukele in El Salvador and threaten or try to close the legislature.”

Some of those concerns were apparent during Petro’s time as mayor of Bogotá from 2012 to 2015. During his term, poverty in the city declined and he found some success introducing new social programs, such as drug treatment centers. But when his plan to put a city agency in charge of trash collection led instead to garbage piling up on the streets, Petro was temporarily removed from office. While even many critics (alongside the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights) say his dismissal was excessive, that public policy failure has been hard to shake.

“He’s not a radical thinker and he’s not a radical reformer. He’s more an incompetent populist. When he was mayor of Bogotá, he was not very good at doing big changes,” Miguel Silva, founder of the Colombia-based consultancy Galileo 6, recently told The AQ Podcast.

Even so, after two previous attempts at the presidency, Petro—currently polling around 38% for the first round—has never had a better shot at becoming president. Colombians are frustrated with the status quo and for many Petro speaks credibly about the ills facing the country.

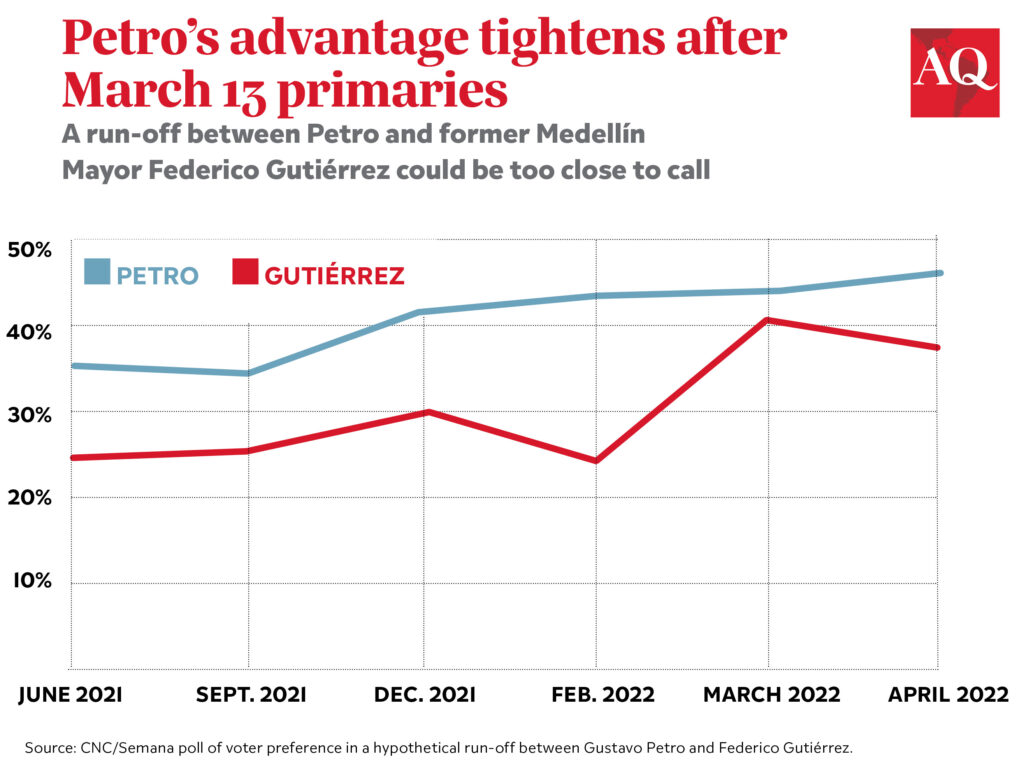

His main rivals also face obstacles. Former Medellín Mayor Sergio Fajardo fared poorly in March 13 primaries and is now polling under 10% (although he did nearly recover from similar poll numbers at this stage in 2018). Another former Medellín mayor, Federico Gutiérrez, is now polling close to Petro in a hypothetical second round, but is associated with the deeply unpopular Duque government.

With so many voters looking for change, Petro’s pitch may finally find a receptive enough audience for him to get over the hump.

“Petro isn’t yet defeated and he isn’t yet victorious. It’s still an open race,” Reina told AQ. “His opponent right now is anti-Petro sentiment, more than a single candidate.”