This article is part of AQ’s special report on Latin American mayors.

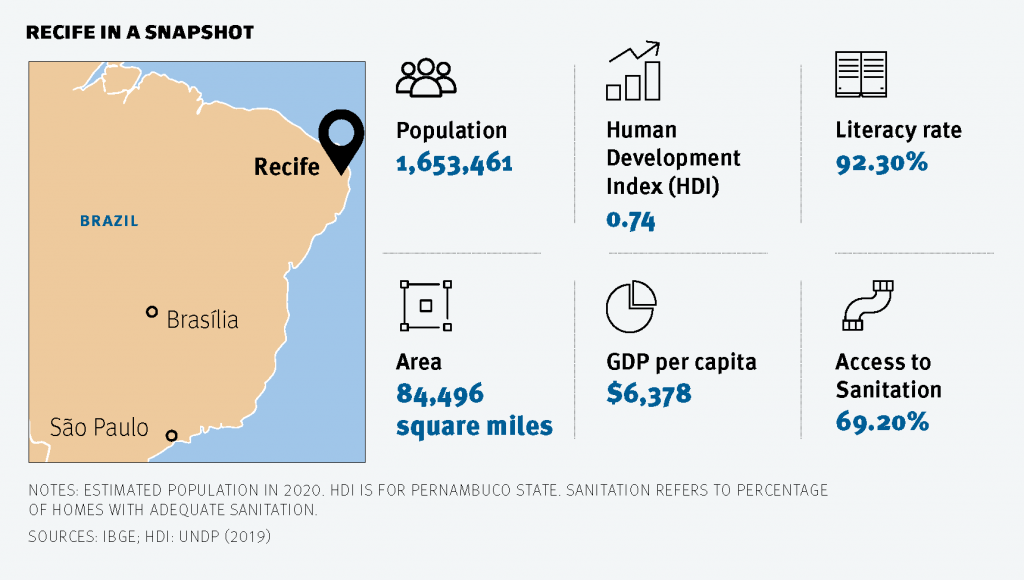

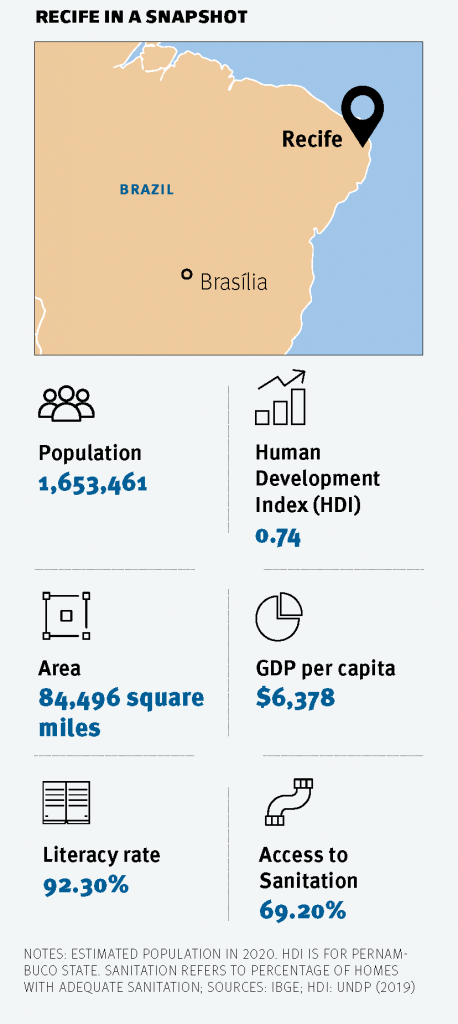

RECIFE, Brazil – Three days before the 2020 runoff election for mayor of Recife, a regional capital in northeast Brazil, João Campos turned 27. His victory was national news. Not only did it make Campos the youngest mayor ever of a state capital in Brazil, it also handed him one of the country’s toughest jobs: managing the capital with the worst income inequality in a country known for its gap between rich and poor.

The attention Campos received was largely because of the political weight of his family name. His late father, Eduardo Campos, and great-grandfather, Miguel Arraes, two of the most charismatic politicians in the history of the Brazilian northeast, were both governors of Pernambuco and presided over the Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB). After Eduardo Campos died in a plane crash while campaigning in the 2014 presidential race, João was thrust into the spotlight.

Campos was determined to both create his own legacy and revitalize the political franchise that had suddenly fallen into his hands. At the time, he was studying civil engineering. Four years later, at 23, he was elected to Congress with more than 460,000 votes, a state record. Before completing his second year in office, he launched his bid for mayor and won – this time in a clash with his own family: He bested his cousin, Marília Arraes from the Workers’ Party, in one of the toughest-fought campaigns Recife has ever seen.

Campos is a politician of his time, making official announcements to his more than 370,000 followers on Instagram. But Campos has used digital innovation to do more than grow his own profile. Consider Conecta Recife, the app that allows residents to schedule their COVID-19 vaccinations without standing in line. The well-organized initiative reduced the risk of contagion and drew widespread praise, even from political opponents.

“In four years, our commitment is to digitally transform this city,” said Campos, who created a secretariat dedicated to making city hall services more accessible. “We want to mirror the success we’ve achieved during the vaccine rollout in other municipal services.”

With his father’s charisma and blue eyes, Campos expects to be compared often to his forebearer. He also knows he bears the burden of managing a city with more than 1.6 million inhabitants and social cleavages that have only worsened during the pandemic.

Conecta Recife, the app that allows residents to schedule their COVID-19 vaccinations, drew widespread praise, even from political opponents.

For example, Recife has yet to relocate families living in the stilt homes crowding its riverbanks or in precarious housing clinging to its hills. The city has a housing deficit of more than 60,000 homes, and Campos’ predecessor invested little to correct the shortage. With no money to finance large-scale construction of new units, Campos is betting on improving the municipality’s credit rating to negotiate gentler terms for international bank loans to pay the bills and honor his campaign promise to build 3,000 new homes in the next four years.

Urban mobility is another challenge. The city has long prioritized private cars over public transportation, and while Recife’s flat terrain is ideal for cycling, it does not have dedicated bike lanes connecting major roads.

“Our commitment is to build 100 kilometers (62 miles) of bike lanes, linking the southern and northern areas of the city. This has been done all over the world,” Campos told AQ, allowing that he is willing to pay the political price of reducing the space for cars in a capital known for some of Brazil’s worst traffic jams.

Campos, unsurprisingly, is quick to name his father and great-grandfather as his political inspirations. But he also touts a name outside partisan politics: Pope Francis.

“He understands that talking is not enough,” Campos said. “We have to act. I believe politics has become just words and discourse. He is a leader who inspires us not just by what he preaches, but by what he does.”

Campos has felt the blowback from a plan to build a large park that displeased the city’s green groups. The project, as planned, would raze a large area of vegetation on the edge of the city’s iconic mangrove wetlands. Campos is pressing ahead though, counting on backing from the city council, where his allies hold a solid majority, and the state governor, who hails from Campos’s party.

At the end of his tenure, Campos knows he will be judged not by his surname but by what he was able to do for Recife — and perhaps what he left undone.

—

Carvalho is a journalist and executive editor of Jornal do Commercio in Recife, Pernambuco