This article is adapted from AQ’s latest issue on China and Latin America

On the evening of May 17, 1980, five masked men entered the village clerk’s office in Chuschi, Peru, tied up the clerk, and set fire to a stack of paper ballots intended for the next day’s election. Peru was about to vote in its first presidential contest after 12 years of military rule. But nearly four decades later, the country is still reckoning with what began the evening before: a bloody attempt at revolution by the Shining Path, a Maoist rebel group that would terrorize Peru for the next decade and into the 1990s.

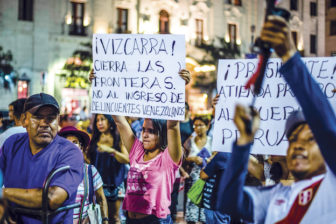

The conflict left some 70,000 people dead at the hands of Shining Path terrorists and the police fighting against them. Today, the supporters and family of Alberto Fujimori, the imprisoned former president often credited with ending the conflict, continue to shape politics despite his conviction for crimes against humanity. Leftist parties, meanwhile, struggle to break through in a population scarred by the Shining Path’s barbarism.

The publication of The Shining Path: Love, Madness, and Revolution in the Andes is thus an important part of Peru’s next chapter. The book, by Miguel La Serna, an historian at the University of North Carolina, and Orin Starn, an anthropologist at Duke University, offers a comprehensive history of Peru’s war with the Shining Path, enhanced by the authors’ exclusive access to some of the conflict’s key protagonists.

In The Shining Path, Starn and La Serna give readers an honest assessment of both sides of the conflict, including the state’s often shameful approach to ending it. They trace the rebel group’s evolution from a bookish political organization confined to the halls of a small university in Ayacucho to a merciless guerrilla army with what at times seemed like a real shot at overthrowing the Peruvian government. Reflecting the authors’ backgrounds in anthropology and history, the book’s intimate human stories are contextualized by both Peruvian and world history.

Though the book charts the lives of Shining Path’s leadership, including “chairman” Abimael Guzmán, its highlights are found in its focus on the conflict’s heroes, not its villains. La Serna and Starn explore the Shining Path’s toll on Peru through the eyes of five brave individuals: Narciso Sulca, a peasant farmer who defended his community against the rebels; Gustavo Gorriti, a journalist whose investigations into state abuses made him a target of the government; María Elena Moyano, a popular Afro-Peruvian shanty town leader who the Shining Path assassinated for her activism against the group; Marco Miyashiro, a young intelligence officer whose critical role tracking down Guzmán was largely forgotten; and Mario Vargas Llosa, the acclaimed writer who ran for president at the height of the conflict.

La Serna and Starn interviewed more than 200 people for The Shining Path, traveling across Peru and to Spain, Italy, Canada, the U.S. and Sweden. The authors’ access to former Shining Path leadership dramatically enhances the book’s insight into how the group operated. Their research included six all-day interviews with the incarcerated Elena Iparraguirre, Guzmán’s second wife and top lieutenant following the death of his first wife, Augusta La Torre.

Throughout the book, the authors dissect the Shining Path’s apparent contradictions, including the odd timing of a communist insurrection taking place just as the Soviet Union was collapsing and China was beginning to embrace the global economy. They note the ironies of an armed group that initially organized around a strategy of rural conquest, but ultimately turned to senseless urban warfare. The Shining Path also explores the role of women at the top of the group’s hierarchy, following the trajectories of Iparraguirre and La Torre.

At a time of intensifying political tribalism and historical revisionism across the Americas, Starn and La Serna aim to “chronicle rather than to pass judgment, without imagining it is ever possible to do one without the other.” Ultimately, their earnest, agenda-free account of the Shining Path is a welcome addition to the canon of Latin American history and to the conversation on Peru’s future.

The Shining Path: Love, Madness and Revolution will be available on April 30.

—

O’Boyle is a senior editor for AQ