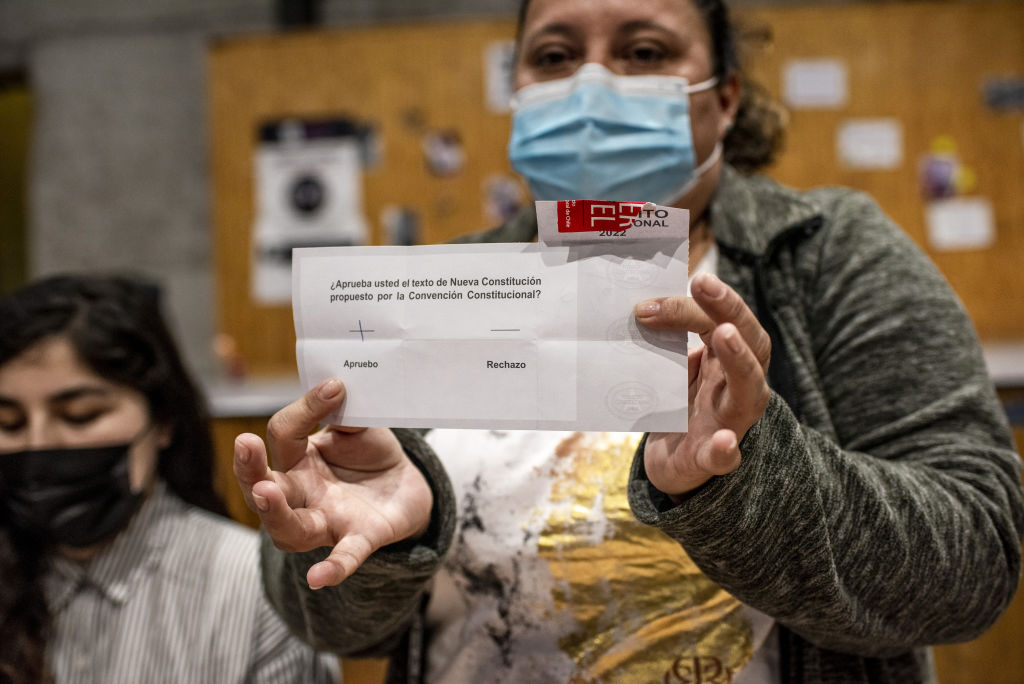

On January 11, Chile’s Congress passed a bill that starts a new process to replace the country’s Pinochet-era constitution. The bill now goes to President Gabriel Boric to be signed into law. Last September, 62% of voters rejected a proposed constitution amid criticism of the document and the constitutional process itself. This new process will bring voters back to the polls twice this year: First in May to elect a 50-member constitutional council tasked with drafting a document in time for a December referendum on the proposed constitution.

AQ asked observers to share their impressions of the new plan and what kind of constitution it might produce.

Javier Couso, professor at Universidad Diego Portales and at the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands

Four months after the resounding rejection of a new charter in September 2022 and following agonizing negotiations involving almost all political parties, Congress finally approved a second constitutional process. This time the drafting of a new charter will be done by both a popularly elected body and a group of experts designated by Congress. In March, the group of experts will start drafting the blueprint of a new constitution, and in June an elected body of 50 members will take that blueprint and work for five months on a final draft. That text will then be reviewed by the group of experts and submitted to the Chilean people for ratification in December.

Although intricate, this process is seen as more likely to succeed than the previous one, both due to the lessons learned and because it is forecasted to produce a moderate text. Indeed, most observers expect a shorter, less programmatic document, which—for that very reason—would be more likely to be approved in the exit referendum. Having said this, critics from the radical left are concerned that the process might be too elitist. More optimistic observers see this new constitutional process as a way to strengthen democracy in a country that has been in institutional trouble for more than three years.

María Jaraquemada, executive director of Chile Transparente

As incredible as it may sound, Chile is paving its way toward a new constitutional process in 2023. Despite the low levels of trust in Congress (8%) and political parties (4%), almost all the parties represented in Congress (this time the Communist Party and all those within the Frente Amplio, President Boric’s coalition) were part of the agreement made in December. Even some political movements created during the previous process (like the Amarillos and the Demócratas) signed the new agreement to make this possible. This is a sign that their commitment to the process has continued even after the unexpectedly strong rejection of the proposal by 62% of voters in the September referendum.

The new process was negotiated for almost 100 days, incorporating lessons learned from the previous one. This will probably lead to a better result and a document that is in the middle between the proposal President Bachelet made in 2018 and the one that was recently rejected. To create legitimacy and citizens’ trust, it will be important that members of the expert committee (24 people nominated by Congress) aren’t seen as controlled by Congress or as having conflicts of interest. Similarly, it is key that the constitutional council (50 popularly elected members) is not involved in constant struggles or controversies. People will probably be less interested in this process, as there’s a kind of “constitutional exhaustion.” In order to prevent a new failure, prudent positions will most probably prevail over more extreme views.

Patricio Navia, professor of liberal studies at NYU and professor of political science at Universidad Diego Portales

The second try at constitutional writing in Chile has all kinds of safety provisions. The elected body will be limited in what it can do, constrained by a 12-point set of principles that it must adhere to and by two non-elected bodies: A 24-member committee of experts that will have veto power on what gets written into the new text and by a 14-member committee of jurists that can also modify the wording of the text to make it comply with Chilean legal tradition. The rules are written so that the convention deliberates with a leash, straitjacket and chaperones making sure that it will not go rogue. Thus, the expectation is that the new constitution will be a dull document, as constitutions normally are. There will likely be a long chapter of social rights, inclusive language, and the recognition of Indigenous people. But just like when a vacation turned sour and everyone had a horrible time, the next time around, those involved are making sure that everything goes smoothly.

Robert L. Funk, assistant professor of political science at the University of Chile’s Faculty of Government and a partner in Andes Risk Group, a consulting firm

The consensus seems to be that the new constitutional agreement takes into account some of the excesses of the previous process, providing some limits to the upcoming discussions. Because the agreement emerged from cross-party discussions, these limits may be considered as a minimum consensus — almost a social contract — regarding what Chile’s institutional structure ought to look like. The limits underscore, among other things, the importance of a bicameral Congress, and the relevance of executive control on fiscal spending. At the same time, the changes made to the process itself — for example, the different electoral system used and the role that the committee of experts will play — seek to strengthen the role of political parties and reduce the influence of independents, maintaining space for democratic deliberation in the convention itself but with the participation of experts to mold and guide discussions.

Although I do think the design of the new constitutional process is an improvement on the previous one, I am slightly agnostic about the committee of experts and its ability to truly influence the discussion. Additionally, most of these “experts” will be people with political experience or academics with some sort of party affiliation, such that the committee could become little more than a mechanism that provides a veneer of academic legitimacy on what will still be, ultimately, a political process.