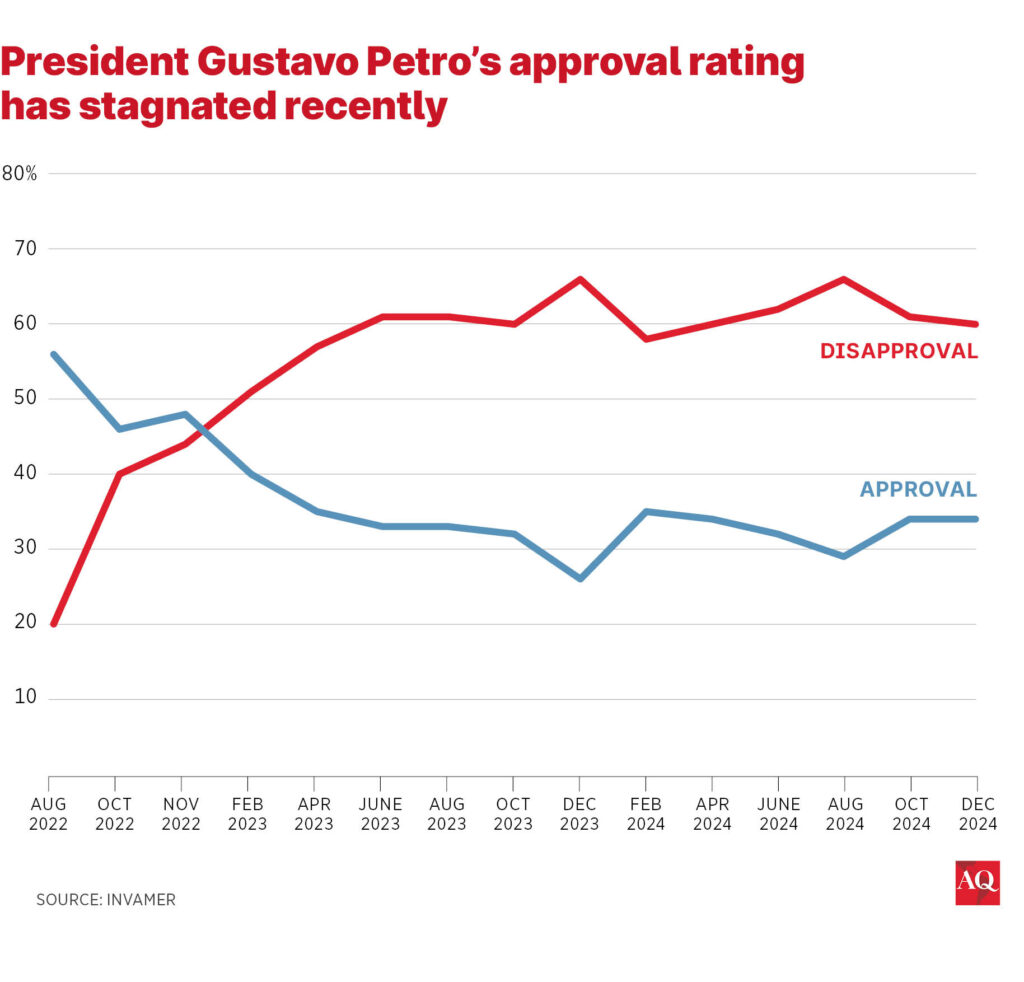

BOGOTÁ —The clock is ticking for Colombia’s president, Gustavo Petro, as he heads into his final full year in office amid a challenging political environment. While his approval rating has remained steady at around 34% — at much lower levels than when he began his term in 2022— his relationship with Congress is far from amicable, and that tension may define a good part of his legacy.

Petro ended 2024 by making the unusual decision to issue the national budget via a presidential decree, a move that seemed impossible just a few months ago. It’s the first time since 1904, in the aftermath of a civil war and the loss of Panama, that something similar happened with Colombia’s budget. This time, circumstances were less dramatic, but the cause was the same: a lack of legislative support. In the end, while Congress did not approve or reject the government’s proposal, the Constitution allows the president to adopt the original text and move ahead with a decree to break the impasse.

The decision left two key conclusions plainly visible. With 19 months to go in his four-year term, the Petro administration’s political weakness is increasing. Things are very different from when he had the support of most parties at the start of his term. As a result, all the significant reforms the president wanted last semester either failed or did not receive final approval from Congress.

According to a report by Orza, a Bogotá-based political consultancy firm, during the first session of the present legislature (between July 20 and December 16), only seven of the 1,011 bill proposals considered by Congress were approved. The government introduced two, and lawmakers submitted five.

Proposals regarding health and labor reforms will be considered this semester, two years after the first versions were presented, and no one is betting that Petro will be successful. According to Interior Minister, Juan Fernando Cristo, the government will also push a project to reshape the agrarian jurisdiction in the upcoming legislative session starting February 16. At the end of December, a tax reform, which proposed additional taxes that would have given Petro’s government more room to spend, was soundly defeated. No wonder Orza considers that the upcoming discussions represent Petro’s “last train” to create a legislative legacy.

On the offensive

Instead of sending conciliatory messages towards key sectors of the political spectrum, Petro decided to go on the offensive. During a speech in December in Barranquilla, the president said: “Damn the parliamentarian who destroys his own people’s prosperity through laws.” In response, the head of the Senate demanded respect.

This setback leads to a second conclusion: Colombia’s fiscal troubles are piling up and have become a significant headache. Although final numbers are still pending, the deficit would have grown from 4.2% of GDP in 2023 to almost 6% last year.

Tax revenues were well below target in 2024 due to various factors. These included mediocre economic performance, legal decisions that affected the 2022 tax reform, overly optimistic assumptions, and self-inflicted wounds, such as tax withholdings that had to be reimbursed. While a cut equivalent to 5.6% of the 2024 budget was approved at the end of November, experts demanded twice as much reduction.

A challenging 2025

Things might be even more difficult this year. Fedesarrollo, the nation’s most important economic think tank, has said that additional savings equivalent to 8% of the budget would be needed. Again, expected revenues seem to be inflated compared with official projections, such as the Long-Term Fiscal Framework published last June.

Finance Minister Diego Guevara, who replaced Ricardo Bonilla in December after his name was associated with the worst corruption scandal of the present administration (Bonilla denies any wrongdoing), will have to manage such a scenario. While he is respected, the question is whether the new head of the government’s economic team can stand up to his boss when strict measures are needed.

A couple of recent decisions illustrate these doubts. Last month, the president said the minimum wage would rise 9.5% (11% if a transportation subsidy is included), almost twice the 2024 inflation rate. This would pressure prices and public finances because of payroll expenses and pension outlays. Given the difficult fiscal situation, the lack of moderation is concerning.

Earlier this month, after truck owners threatened to strike, the minister of transportation convinced eight road concessions to defer a toll increase by six months after meetings the finance minister attended. As in the past, the Treasury will have to cover the gap.

In response, Guevara is trying to calm the markets. In an interview with Bloomberg, he mentioned that the deficit specified by the fiscal rule was respected in 2024. “Leftist leaders can’t afford to scare away investors,” he said.

Maintaining the house in order is key for Colombia. Credit default swaps and EMBI levels show that Colombian bonds have a much bigger spread than public bonds from Chile, Peru, or Mexico. There are doubts about keeping investor confidence after seeing Brazil pounded by investors late last year.

An economy gathering steam

One of the more significant fears is derailing an economy that is picking up pace. According to official projections, GDP growth in 2024 will be around 1.8%, three times faster than in 2023. This year, the nation’s central bank expects total output to increase by 2.9%, close to the nation’s economic potential.

However, there are additional risks. On the international side, geopolitical tensions are rising, and Donald Trump’s return to the White House raises further concerns. Internally, investor sentiment is still low, and some crime indicators are rising.

For the first time in 40 years, Colombia will have to import natural gas for its regular needs. At the same time, the government wants to change the rules of the game in the electricity generation sector. Experts have warned that the risk of energy shortages is on the rise.

The future looks challenging for the country with the third-largest population in Latin America. Petro remains mostly unpopular, and his Pacto Histórico coalition’s chances of staying in power seem slim. According to a poll by Invamer, the president’s approval rating in December was 34%, while his disapproval stood at 60%.

As contradictory as it may sound, his likely successor’s name is unclear. More than 50 people intend to run for the presidency in 2026, and no frontrunner has emerged yet. According to a poll by Centro Nacional de Consultoría, the former mayor of Medellín Sergio Fajardo is leading with 13.4% of voter intention.

At the same time, general public opinion is highly pessimistic, even if people feel better personally. Probably, the wet weather that was the norm during the holidays at the end of the year—when blue skies used to be the standard—presages more turbulent times ahead for Colombia, the President included.