BOGOTÁ — The agenda has been set. On Tuesday, February 27 at 3:00 pm, a plenary session of the Colombian Senate, with its 105 members, will reconvene with one issue as its top priority: a complex bill to reform the national pensions “by which the system of integral social protection for the elderly is established.”

The proposal is one of the most critical initiatives that Gustavo Petro’s administration has pursued. After a year and a half in power, Colombia’s president is struggling to pass the keystones of his social agenda: three reforms regarding labor, health and pensions.

Despite the initial promises to have these initiatives approved during the first half of 2023, reality has proven to be much more difficult. None of the proposals advanced as expected, and time is running out for health and pensions, which have to be voted on during the current legislative period ending on June 20. The labor reform was reintroduced, but the chances of Congress considering it are very small.

Why has it been so difficult? First, there is the political reality. The coalition that supports the government has been weakened. In the Senate, the Pacto Histórico and its allies have 46% of the votes, while opposition parties and independents control the rest.

There is a massive effort to persuade some legislators, offering what for Colombians is known as “marmalade,” a term that refers to giving posts and money in exchange for support to get bills discussed in the legislature. The strategy may be successful, but the price will be steep, and some legislators will start bargaining for more.

Furthermore, the reforms are very controversial. In the case of labor, it would strengthen unions and increase costs while the economy is struggling. According to official estimates, Colombia’s gross domestic product barely grew 0.6% last year—falling behind the projected 1.2% expansion—the weakest performance since 1999. The GDP even unexpectedly shrank 0.3% in the third quarter.

The health reform would eliminate the insurance model that covers 97% of the population and has one of the lowest out-of-pocket expenses in the world. A new prevention-based system would be established, while a big official agency would disburse money to hospitals, clinics and other providers.

While the discussions crawl ahead in Congress, Petro’s administration is in the process of suffocating private healthcare providers. Ultimately, it may get away with its plan even if the health reform stalls.

The pension reform

Things look different in the case of pensions. For a start, very few people like the present system where the public pay-as-you-go model coexists with the privately administered individual savings account model.

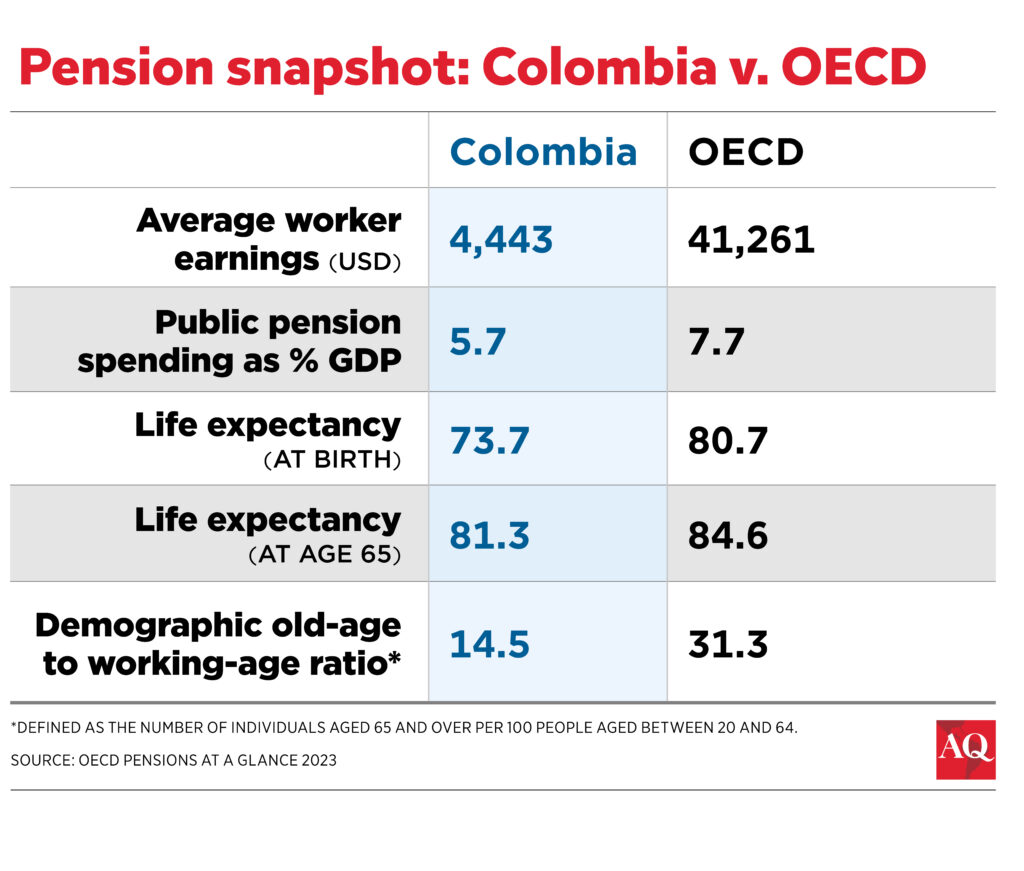

For high-income individuals, benefits are unbalanced, causing them to favor the public model. As a result, there is a substantial public subsidy that increases income inequality in one of the most unequal societies in the world. Since there is a deficit in reserves, the national budget must cover the gap.

At the same time, the whole system only covers 18% of the population. This means that presently almost five million Colombians have no coverage despite having reached the retirement age.

This is why a pillar system with different degrees of solidarity was proposed. People at the bottom of the income pyramid would receive a monthly stipend to protect them from falling into extreme poverty.

Citizens at the top would not receive a large subsidy, since there would be a cap and only one public system based on the pay-as-you-go model. If participants want an additional pension, they can complement it by saving in an individual account. In other words, instead of competing, both models would be complementary.

It is difficult to oppose a proposal that would eliminate subsidies for high-wage earners and help older Colombians. And people over 60 are one of the groups where poverty is most common.

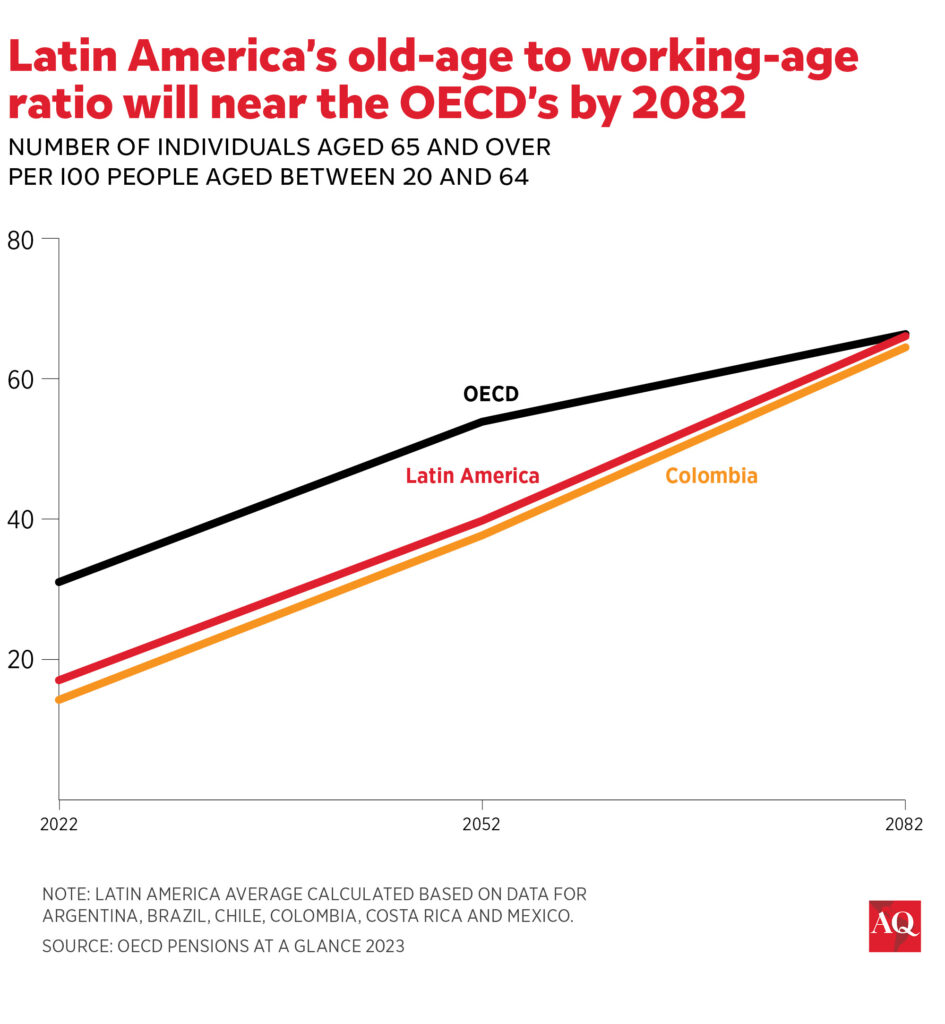

However, doubts persist. First, the proposed changes would increase coverage by only one percentage point, according to government figures. Second, the average Colombian is getting older, and by the middle of the century, the workforce would struggle to finance pensions for retirees. Third, the size of the deficit would increase dramatically, from 83% of GDP to 127% by 2100, according to Asofondos, the association representing private pension administrators.

But the biggest concern is the following: Since pension contributions from the payroll would go to a public entity (Colpensiones), there would be no need to finance the present deficit. With clear political implications, this would allow the government to increase expenses by almost 2% of GDP.

At the same time, Colpensiones must be professional in administering the funds it would receive. There are major doubts about this capacity, based both on history and the current head of the entity: a former senator and labor leader involved in different scandals.

Now that the debate in the Senate will begin, most legislators will likely support a toned-down version of the original proposal. After clearing this hurdle, the House of Representatives would tackle the reform, and the controversial parts of the proposal would resurface.

But even if there is a government victory, implementation will be challenging. Many questions remain unanswered, including the eventual transfer of the more than $100 billion in reserves that have been invested by the private funds.

One proposal is to delay the start of the new system until January 1, 2027. This would mean Gustavo Petro would not take advantage of the extra spending room that the pension reform would give the Ministry of Finance. As they say, the devil is in the details, and at this point in Colombia, many devils are lurking.

__

Ávila is a senior analyst at El Tiempo and a political consultant in Bogotá, Colombia