Correction appended below.

Peru is losing its talented young people. According to a poll published in September by the Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, a well-known think tank based in Lima, 60% of those between the ages of 18 to 24, and 51% of people between 25 and 39, say they have plans to leave the country in the next three years. It seems that Peru is yet another Latin American nation whose youth have decided to seek a future elsewhere.

These numbers have confirmed a trend that I had noticed for some time already in my personal life. I left Lima for the United Kingdom for the second time in 2021, having previously lived here between 2013 and 2015. But unlike during that earlier period, this time a great many of my Peruvian friends are living here as well. Several others have chosen to reside in the United States or Canada. And except for maybe one or two, none have plans to return.

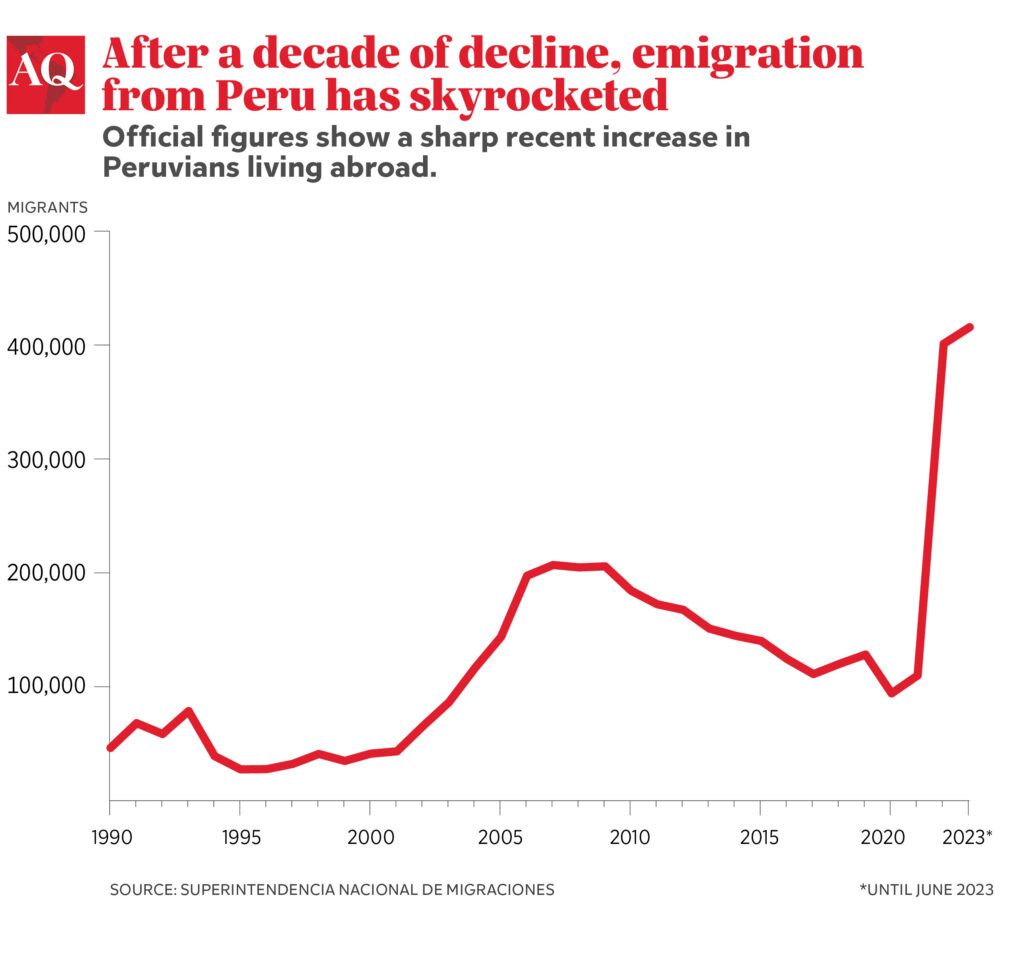

At a first glance, stories of Peruvians migrating abroad in search a better life are far from uncommon. My parents’ generation saw a similar process in the 1980s and 90s, during the dual crises of hyperinflation and violence caused by the Shining Path. And Latin Americans in general have historically been migrants. Just between 2010 and 2020 there was an 82% increase in migration within the region, largely driven by the 7 million Venezuelans who have fled their country escaping Nicolas Maduro’s regime.

What makes the phenomenon difficult to accept this time is that, for a brief period, my generation thought they would not have to repeat their parents’ experience. But Peru’s ongoing political and economic turmoil is driving people away once again. In 2022, 401,740 Peruvians left the country and did not travel back, a four-fold increase from the 110,185 who did the same in 2021. By June of this year, that number grew to 415,393.

After IEP’s figures were published, I spoke to around 20 Peruvians between the ages of 18 and 40 who either currently live abroad or plan on leaving the country in the near term. Several of them felt that Peru no longer offered the professional opportunities they sought, and they spoke of fear and hopelessness when asked about the country’s prospects. “I’ve always been proud of being Peruvian, but I’ve decided to leave and not come back because, unfortunately, I feel that Peru is on its way to authoritarianism,” said Alvaro Olivares, 38. Naomi Shimabukuro, 35, who lives in Australia, agrees: “Despite living abroad, I read and listen to the news every day, and I know the country’s future is very uncertain.”

A lost optimism

It’s a huge shift from the prevailing attitude ten years ago, when I was in my mid-twenties. Back then, my generation dreamt of studying abroad if they could, but many wanted to return. As the fastest-growing economy in the region, thanks to the commodities boom and a growing agribusiness sector, Peru seemed to finally offer the economic opportunities that we sought. At the same time, while Peruvian politicians have never been particularly respected, the country still felt largely governable. That’s because it was the last time the president’s political party held a majority in Congress. Relations between the executive and legislative were nowhere near as fraught as they have been since 2016, when Pedro Pablo Kuczynski was elected but Keiko Fujimori’s party dominated parliament. President Ollanta Humala (2011-2016) could more easily pass key policies, such as the reform of the civil service, and the government implemented social programs like conditional cash transfers and higher education scholarships for underprivileged youth. Peruvians believed the future was looking brighter. According to pollster Ipsos Apoyo, in July 2015 44% said they felt optimism and hope when they thought about Peru.

That number dropped to 26% in July 2022. Now, young people want to build a life elsewhere. “I’m not going to waste my thirties in a country where there is no longer a future. [The situation now] is very different from Peru between 2010 and 2012. That dynamism and hope doesn’t exist anymore,” said Miguel Galvez, 33, who lives in Spain.

The end of the “miracle”

It’s hard to argue otherwise. The “Peruvian miracle”—the apparent ability of the economy to maintain high levels of growth despite political instability—is now undeniably over: GDP rates were negative for four consecutive months by August, pointing to a recession for this year. The effects of this contraction are stark. In the same poll mentioned at the beginning of this article, 57% reported being unable to afford food at least once in the last three months.

Even more worryingly, crime is worsening in a way my generation has never experienced before. Local media is full of daily reports of extortions, killings, and even bombings carried out by gangs, something that was unheard of even a year ago. The percentage of people over 15 who have been victims of crime has increased from 17.6% in January 2021 to 26.9% by June 2023, and 72% of Peruvians say they feel unsafe walking down the street at night. Several of those I spoke to who plan on leaving the country cited insecurity as the main reason. “Trujillo, where I live, has become a no-man’s land. It is frustrating to be constantly afraid of being robbed or even murdered over the small business we have,” said Elizabeth Calcina, 39, who is thinking of moving her family to Belgium, where her husband is from.

All of these individuals were keenly aware that so many young people emigrating could only hurt the country in the long term. Peru is in dire need of a new political class, of ambitious people who want to work in the civil service or in the private sector. As I’ve written before, millennials are poised to be the next leaders in Latin America and will determine the region’s future. Faced with this reality as a highly educated, politically minded Peruvian, my decision to live abroad is one I constantly grapple with.

Fortunately, a few want so strongly to be part of the change that, unlike the majority, they plan to return. “I feel like I have to give back to Peru,” said Fernando Loayza, 31, who is completing a PhD in the US. “There is much to be done.”

This article was updated at 11:22 a.m. on November 8 to correct Fernando Loayza’s age. He is 31, not 33.