SANTIAGO – The struggle between reason and passion has occupied minds since classical times. The Stoics, Adam Smith, even Pierre Elliot Trudeau have thought long and hard about how to control the passions. For Sigmund Freud the passions were manifested in the id, which was like a strong-willed horse, whereas the ego was the rider, trying to control it, ideally, with such self-awareness that it would look like both were in sync.

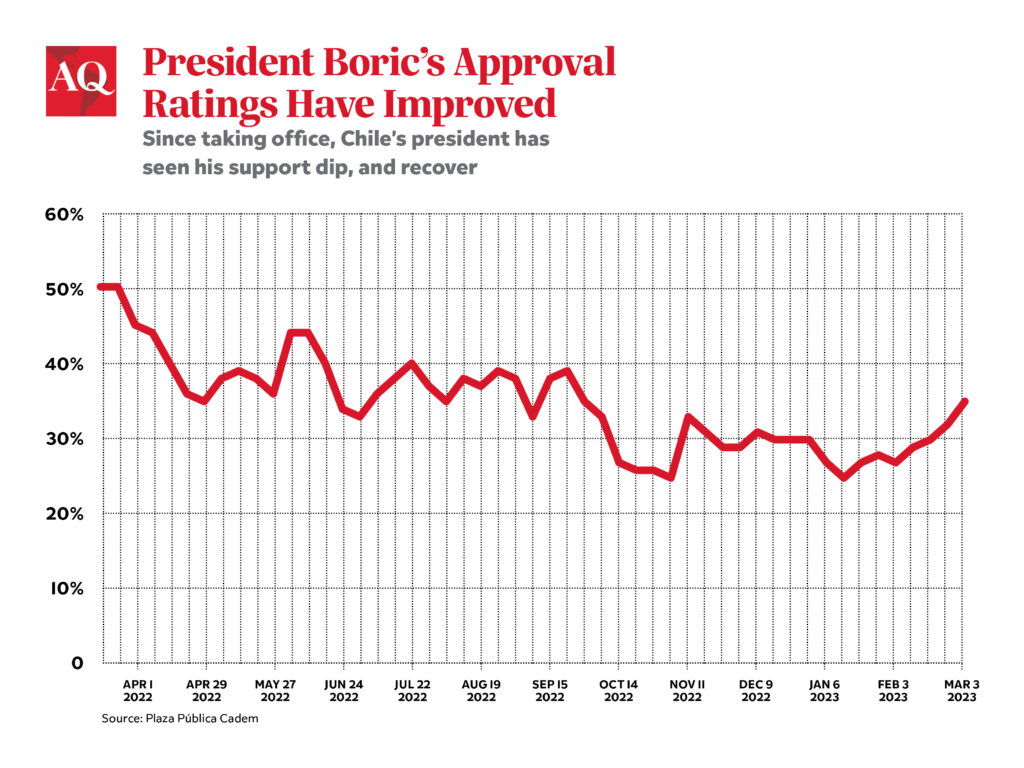

During his first year as president, Gabriel Boric’s id and ego have been going at it, often in public view. So far, Boric’s ego has dominated his id in large measure thanks to simple political mathematics: he doesn’t have the legislative majority that would let him implement the kinds of policies he once championed.

As is well known, Boric’s path to the presidency began in university politics, as a rabble-rousing, authority-questioning leader of student strikes. His success in marshalling the student protests of the early 2010s catapulted Boric and some other student leaders to Congress, where he became a rabble-rousing, authority-questioning deputy.

The new left that Boric and his colleagues sought to construct resulted in a new coalition, the Frente Amplio (Broad Front), which questioned the parties of the traditional left and rejected the timidity of the center-left Concertación and the transition years. Much of this was generational: Boric represented an age cohort that was barely alive when General Augusto Pinochet handed the presidential sash to the democratically-elected Patricio Aylwin. The existential issues of the young were very much planted in the 21st century: gone was a fear of communism, in was a fear of global warming.

Herein lies Boric’s id: impatience bordering on anger with regard to all the issues that inspire today’s progressives, from gender equality to protecting the environment to accusing Israel of colonialism and genocide.

The vicissitudes of political fortune, however, can force changes of heart or mind. In the 2021 presidential election run-off, Boric was suddenly confronted with José Antonio Kast, a far-right defender of Pinochet, who scared even moderate center-left voters who were suspicious of Boric, and even some on the center-right. Enter Boric’s ego. Boric understood that electoral victory would be his if he kept his id under control. Gone was the unkempt hair and shaggy beard. In came the dark suits and white shirts (although the id drew a limit at ties — a look the president has maintained ever since).

The issue that really dominated Boric’s first year in office, however, was the constitution. The design of a new constitution was part of the cross-party agreement reached in November 2019, in an effort to put an end to weeks of violent protest. From July 2021 to July 2022, 155 elected members of a constitutional convention worked to propose a new institutional structure for Chile. Boric was elected in the midst of the process, and did his best to remain neutral, although it was clear, as Minister Giorgio Jackson stated, that a rejection of the constitution would affect the government’s reform agenda.

But rejected it was, in a national referendum on 4 September. It was Boric’s lowest moment, not only because of the process itself, but because the scale of the defeat (62% to 38%) made clear a far more painful truth: the country was not as progressive and post-modern as the proposed constitution, or the government, thought. People had gone back to worrying about jobs, immigration, and crime – the stuff of everyday politics and policy.

Here Boric’s ego kicked in. His pragmatism led him to recognize the defeat and shuffle his cabinet, bringing in experienced hands to the Interior ministry and the General Secretariat of the Presidency (which deals with Congress). The new ministers in these posts come from the old center-left that the Frente Amplio criticized so much when in Congress.

Herein lies one of Boric’s main challenges going forward. Will the moderate left continue to dominate cabinet and decision-making? As Boric approaches his first year anniversary many expect a cabinet shuffle. The political balance will be telling.

The second challenge is, once more, the constitutional issue. Congress has approved a new process, which will see Boric’s second year again dominated by a constitutional convention. It is becoming clear that Boric has one job: get a constitution approved. To do so, he’ll need to keep in check the far left, which is unhappy with the restrictions and limits that the present process has imposed.

Finally, there’s the task of governing. The Transpacific trade agreement TPP11 is a good example of this: As a deputy Boric had appeared in Congress wearing a ‘#NoTPP’ T-shirt, and his election platform made a point of not including the ratification of the trade agreement. But once Congress voted in favor of ratification, it would have been too costly to stick to his campaign promise. Last month, Chile finally signed on the agreement.

Boric’s ego must, then, extend to the task of everyday governing, especially on those issues – crime, immigration, drugs, violence – about which voters are most worried. They are also the most difficult to tackle successfully, especially for a president who spent years marching on the streets. Boric’s id tells him that law enforcement is oppressive and unduly violent. But the voters, and his ego, are telling him that it is time for the state, not the street, to govern.

—

Funk is assistant professor of political science at the University of Chile’s Faculty of Government and a partner in Andes Risk Group, a consulting firm.