More than two months have passed since Mexico’s general elections, but the results are still taking shape—as are their consequences. It appears that a landslide victory for the ruling Morena party is about to give it more power than any party has had in decades. This amounts to a serious threat to Mexico’s already fragile checks and balances.

Formerly independent and nonpartisan institutions are now under Morena’s control and can be expected to unduly favor the party. The consequences for the Mexican people, as well as for investors, could be far reaching—with implications for energy, telecommunications and other sectors, as well as Mexico’s trade relationship with the United States.

Outgoing President Andrés Manuel López Obrador made several efforts during his presidency to consolidate power by reshaping key institutions, including the National Electoral Institute (INE) and Elections Tribunal. Last year, AMLO pushed through an INE reform that cut its budget, shrank its staff, and made it less independent, supposedly to save money, streamline voting, and prevent corruption. The Tribunal, meanwhile, has been operating with just five of its seven required magistrates for an extended period, a situation that the Morena majority in the Senate has opted not to rectify.

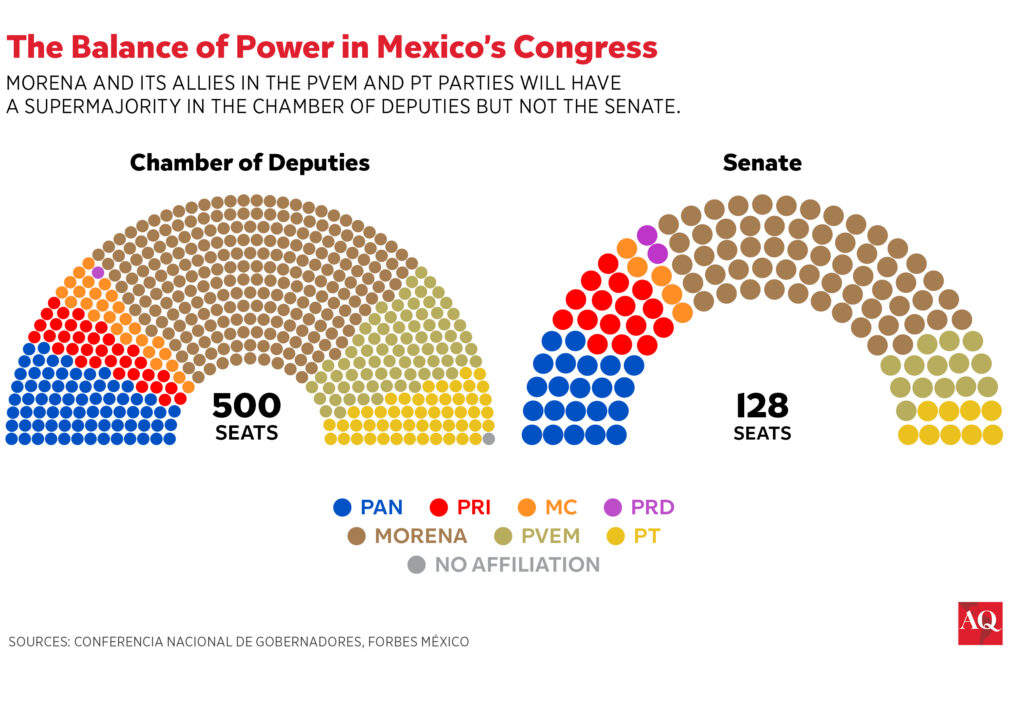

Indeed, the election results themselves appear to be a sign of Morena’s growing influence. The INE and Elections Tribunal handed Morena’s coalition a supermajority in the Chamber of Deputies based on a calculation that was unconstitutional and unprecedented. As a result, Morena’s coalition will control 73% of the Chamber, even though they won just 55% of the vote. This 18% difference far exceeds the constitutional limit of 8%.

It will allow Morena to rewrite the constitution virtually at will. To do so, Morena would need a supermajority in the Senate as well, and it is closing in. On Wednesday, the coalition added the moribund PRD’s two senators to its ranks. It is now just one seat short, and is almost certain to be able to bargain for it.

This new Congress will take office on September 1—a month before AMLO is replaced by Claudia Sheinbaum—and is likely to pass AMLO’s judicial reform while he’s still in office. The reform would fundamentally recast the justice system. The Supreme Court would be shrunk from 11 judges to nine, who, for the first time, would be elected by popular vote. But it goes much further: Over 1,600 federal judges and magistrates would also be selected by vote. This has raised fears that the entire judiciary will be politicized, which could, in turn, gut the judiciary’s ability to act as a check on other branches of government.

Other proposals for the supermajority include the dissolution of independent watchdogs and regulators like the Federal Economic Competition Commission (Cofece), the Energy Regulation Commission (CRE), the Federal Telecommunications Institute (IFT), and the Transparency Institution (INAI). If these proposals are executed, the presidency and the ruling party would not only consolidate a virtually unprecedented degree of power, but also put crucial economic sectors in deep uncertainty; the energy, hydrocarbon, and telecommunications sectors, for example, would be profoundly altered, potentially in violation of the USMCA, creating substantial tension with investors and diplomatic partners.

The closest historical parallel to Morena’s result occurred in 1991, when the PRI and its satellite parties won 66.3% of the electoral vote, and were granted 74% of seats, securing 370 representatives in the Chamber of Deputies. It proved a fateful episode for pluralism.

With that supermajority, between 1991 and 1994, the PRI and its allies (PPS, PFCRN and PARM) reformed the constitution deeply in critical areas, from education to the electoral system to the constitutional recognition of the Central Bank’s independence.

Since then, the Mexican system has slowly evolved into the more pluralistic democratic system we have today. In no election since has any party or coalition achieved the degree of over-representation that Morena’s coalition is about to wield.

The INE and the Tribunal have caused Mexico to take a decisive step backward. Decades of hard-fought reforms aimed at ensuring fair representation, transparency, and checks on executive power are at risk. Today’s pluralism, a cornerstone of Mexico’s democratic evolution, may well become a thing of the past.