MEXICO CITY—Mexico is running out of drinking water. From the arid and desert regions of the country’s north to sun-baked tropics of the south, water shortages are becoming increasingly common—and the national implications are already being felt in the form of mass protests, economic threats, and increasing attention by the leading candidates in the country’s presidential race.

Citizens are angry. In recent months, thousands have taken to the streets to protest water outages, and with good reason. According to the Mexican constitution, access to water is a human right that the government must guarantee. But right now, for an increasing number of citizens in major metropolitan areas and small municipalities alike, their right to clean drinking water isn’t being met. While 57% of Mexico’s population lacks access to a reliable, safely managed water source, 105 of the 653 aquifers in the country are being overexploited beyond their capacity to recharge, a study by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands concluded in 2020. For years, the country has been among the world’s largest per-capita consumers of bottled water, along with China and the United States.

Mexico’s two leading presidential candidates—Claudia Sheinbaum of the ruling Morena party and Xóchitl Gálvez of the Broad Front coalition—are well aware of the national water crisis. Gálvez discussed the issue at length in a recent Senate forum, while Sheinbaum touts water infrastructure projects during her term as Mexico City’s mayor and says she considers water to be a “fundamental issue.”

Other candidates are also paying attention. For Samuel García, the Nuevo León governor who on November 12 registered as a presidential hopeful for the Movimiento Ciudadano Party, water availability has been perhaps the biggest problem he’s been tasked to resolve during his two years in office. It’s likely García will highlight his government’s efforts to solve Nuevo León’s water crisis—including the construction of new dam and aqueduct projects—as representative of what he would do at a national level if elected president.

In Torreón, the capital of the northern state of Coahuila, more than 85% of residents surveyed in July said that water supply was the principal problem for the city of nearly 750,000. And in the central Mexico city of San Luís Potosí, the mayor announced in June that water supply could no longer be guaranteed for the region’s nearly 1 million inhabitants. He said the city had reached “day zero” and that San Luís Potosí would be without water due to cracks and leaks in the region’s most important dam.

Monterrey, capital of García’s state of Nuevo León and leading industrial city of Mexico, is home to more than 5 million people and is set to host a new Tesla plant, soon to be constructed. There, citizens adhere to strict daily rationing schedules, and some have no access to water.

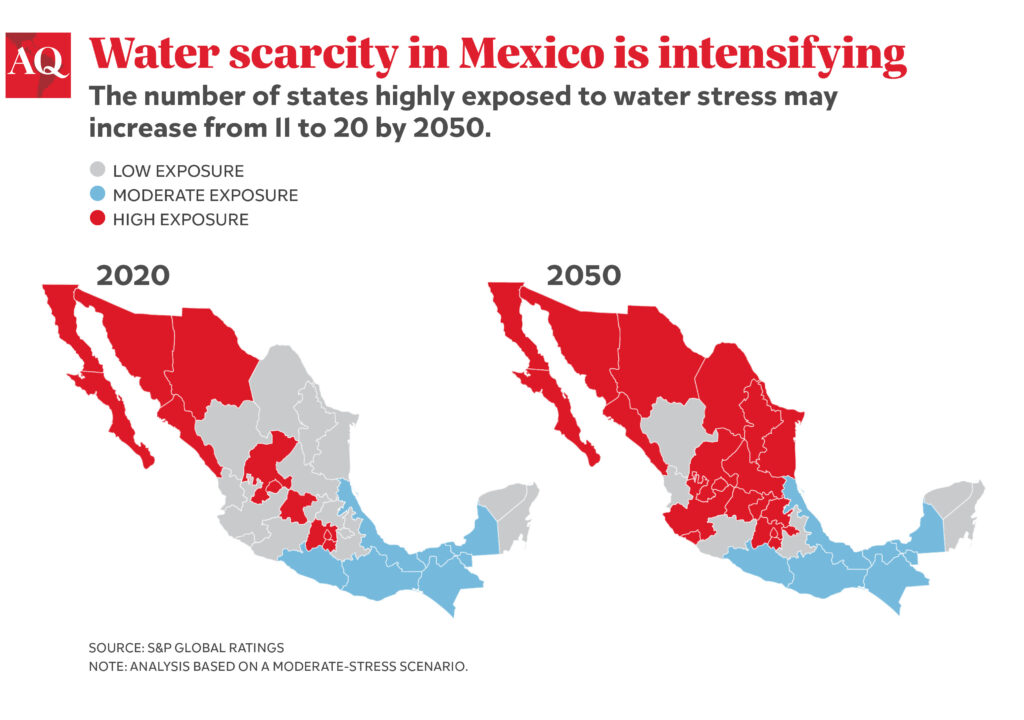

Mexico’s limited water resources could have widespread economic implications and jeopardize some of the billions of dollars in investment and thousands of jobs expected to be generated as part of the nearshoring boom. Executives at major national energy and infrastructure companies say that international businesses considering relocating operations to Mexico have two primary concerns: access to reliable, clean energy and water availability. Companies interested in investment in Mexico are confident they can work around the country’s long-standing security issues. A lack of adequate water supply, however, they say, could be a dealbreaker. A recent study by S&P Global Ratings, a credit risk New York City-based firm, estimated that without adaptation measures, the number of Mexican states exposed to high water stress will almost double to 20 by 2050, from 11 in 2020, eventually affecting their economic growth.

Plans beyond promises

Sheinbaum, Gálvez, and Mexico experts agree that Mexico’s water problems aren’t due to insufficient supply but rather a consequence of poor resource management and a lack of adequate infrastructure, distribution, collection, and treatment systems. While much of Mexico sees plenty of annual rainfall, for the country to assure water supply to residents, dams, aquifers, and distribution systems must be overhauled and updated. This can be a challenging, multi-pronged issue to solve that requires coordination at the federal, state, and municipal levels.

Sheinbaum’s approach to the water crisis on the campaign trail seems likely to rely on reminding voters about the improvements to the distribution system in the Mexico City metropolitan area achieved during her term as mayor. As part of a coordinated effort with the State of Mexico government that began in 2019, Sheinbaum says she and an extensive work group of experts met at least once a month to attend to the issues of clean water supply in the greater metropolitan area and that the efforts have been an undeniable success. In visits to regions of the country where water shortages are a principal concern of citizens—such as Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Oaxaca—Sheinbaum and her team have reminded voters of their successes in the Mexico City area and vowed to implement similar solutions nationwide.

Gálvez, who during her term as a senator repeatedly commented on the need for improved water regulation and legislation, also appears to have a detailed vision for how to address the crisis. In her comments on Sept. 20, for example, she said part of the explanation for reduced water resources in Mexico had to do with deforestation, which she said must be better controlled, and that updated treatment technologies must be introduced to reuse resources for human consumption.

In June, the National Water Commission, Conagua, reported that more than 70% of the country suffered from water shortages amid widespread drought and scorching temperatures. As concern grows for how to address the nationwide water crisis, it seems that the more Mexico’s two lead candidates discuss solutions to the issue on the campaign trail, the better their chances might be to win voter support.

—

Williams is an award-winning investigative journalist and writer based in Mexico City with writing in The New York Times, Bloomberg, El País and many other publications.