Ecuador | Nicaragua | Chile | Honduras | Full List

This page was updated on July 20

A dispersed vote in Peru’s April 11 presidential election sent shockwaves through the country’s establishment, with socialist teachers union leader Pedro Castillo securing a spot in the runoff with just under 19% of the national vote. Keiko Fujimori, daughter of the imprisoned former president Alberto Fujimori, closed in on a spot in a runoff with just over 13% of the vote. Market-friendly economist Hernando de Soto and ultra-conservative Rafael López Aliaga rounded out the top four. In a runoff on June 6, Castillo narrowly defeated Fujimori with 50.1% of the vote.

Over the course of the campaign, AQ profiled the leading candidates, below, who at one point met our criteria as one of the top six candidates polling above 5% in Ipsos polling.

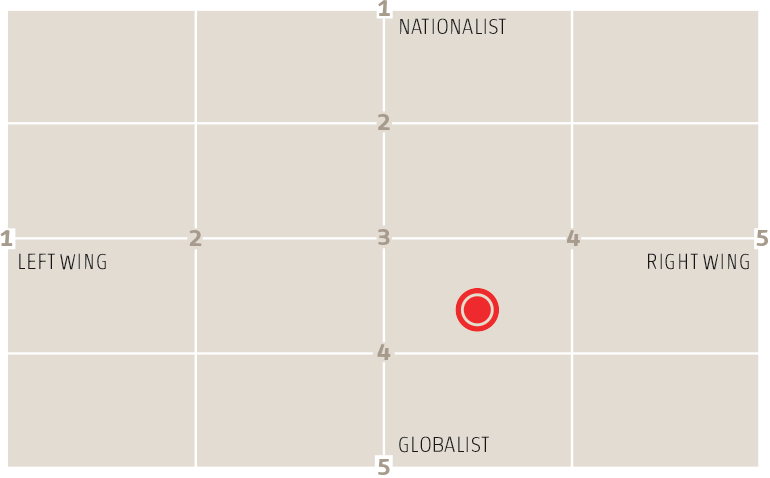

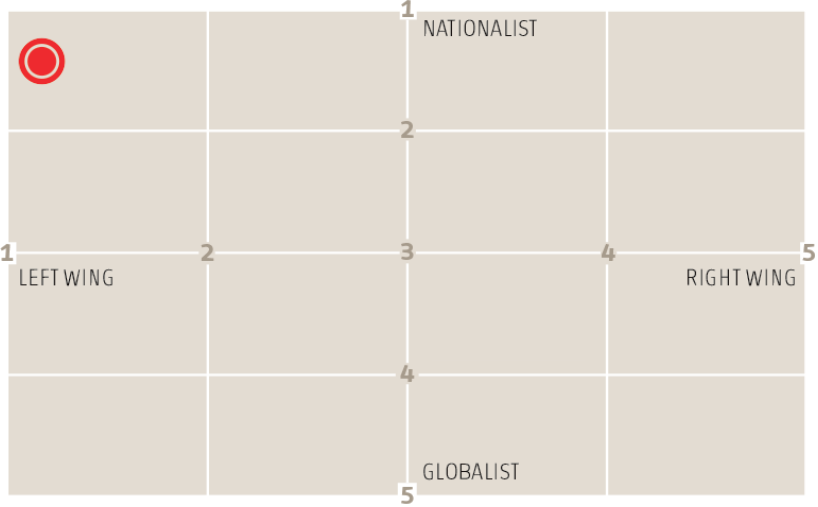

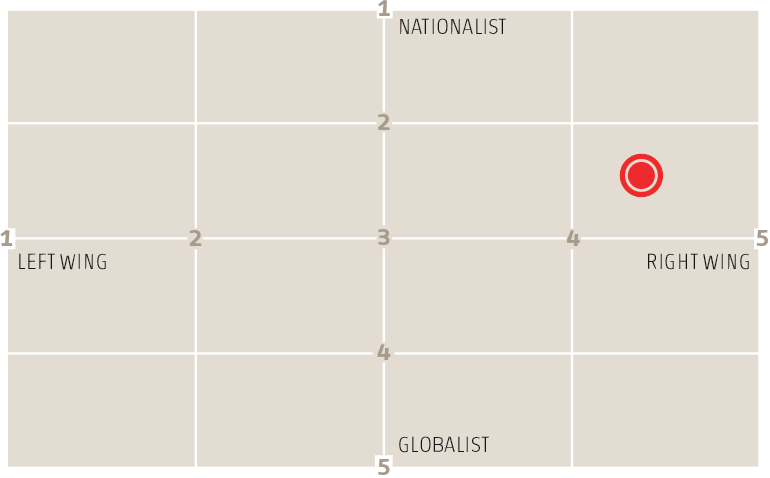

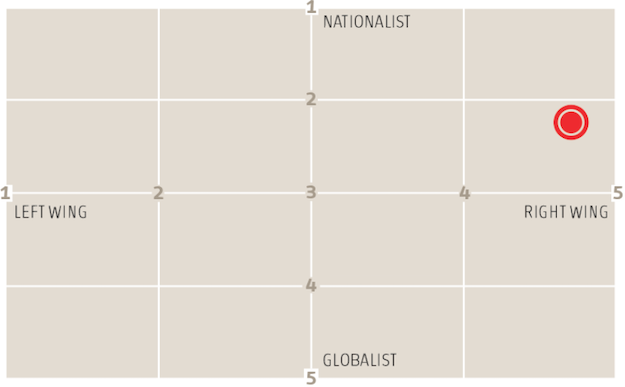

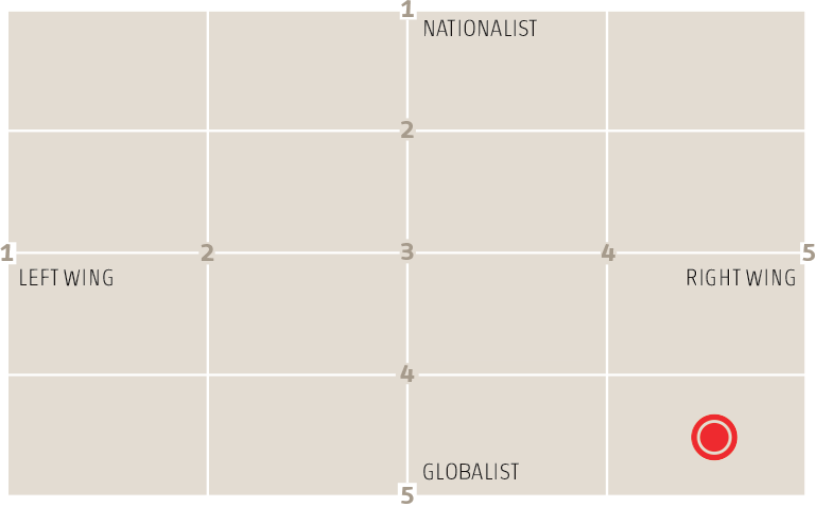

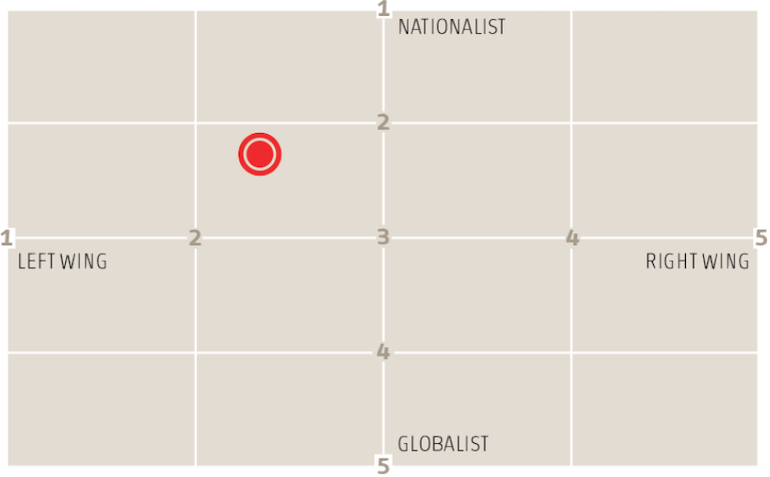

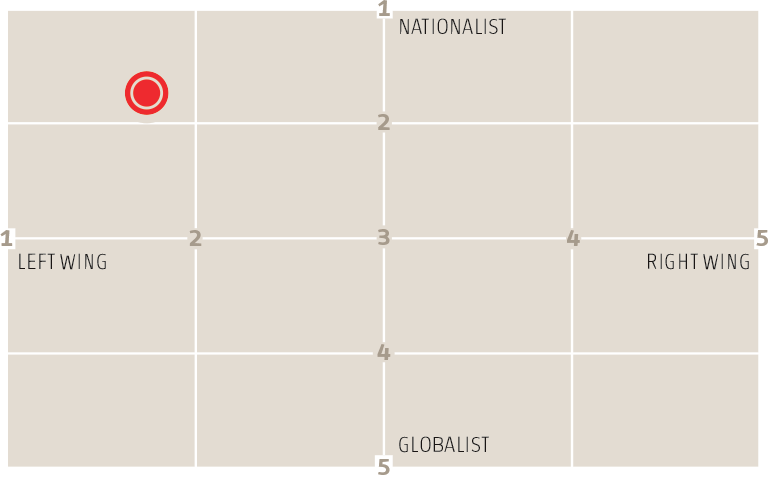

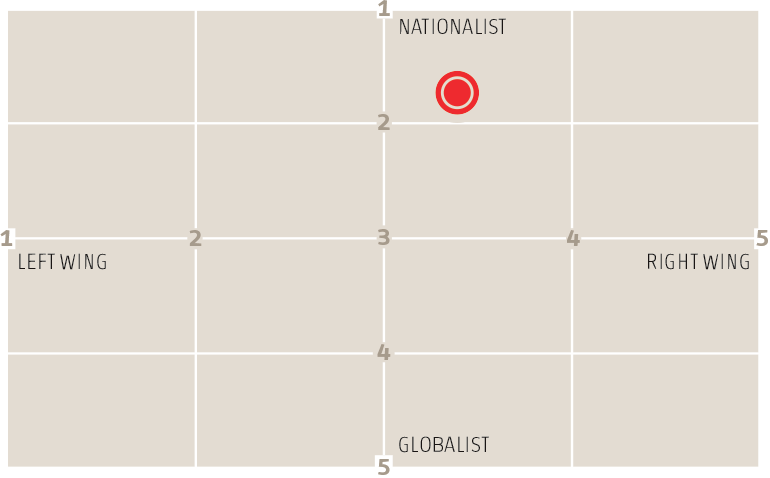

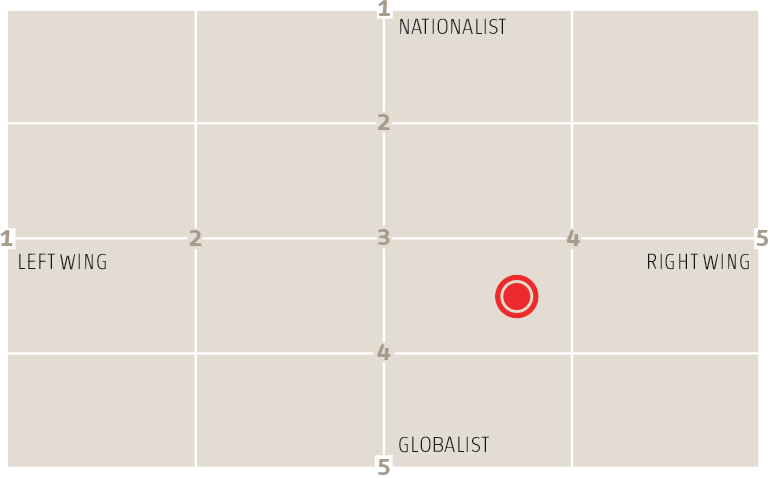

AQ also asked a dozen nonpartisan experts on Peru to help us identify where each candidate stands on two spectrums: left wing versus right wing, and nationalist versus globalist. The results are mapped on the charts below. We’ve published the average response, with a caveat: Platforms evolve, and so do candidates.

Pedro Castillo | Keiko Fujimori | Rafael López Aliaga | Hernando de Soto | Yonhy Lescano | Verónika Mendoza | Daniel Urresti | George Forsyth | Julio Guzmán

Pedro

Castillo

51, teacher and union leader

Free Peru

“The blindfold has just been taken off the Peruvian people.”

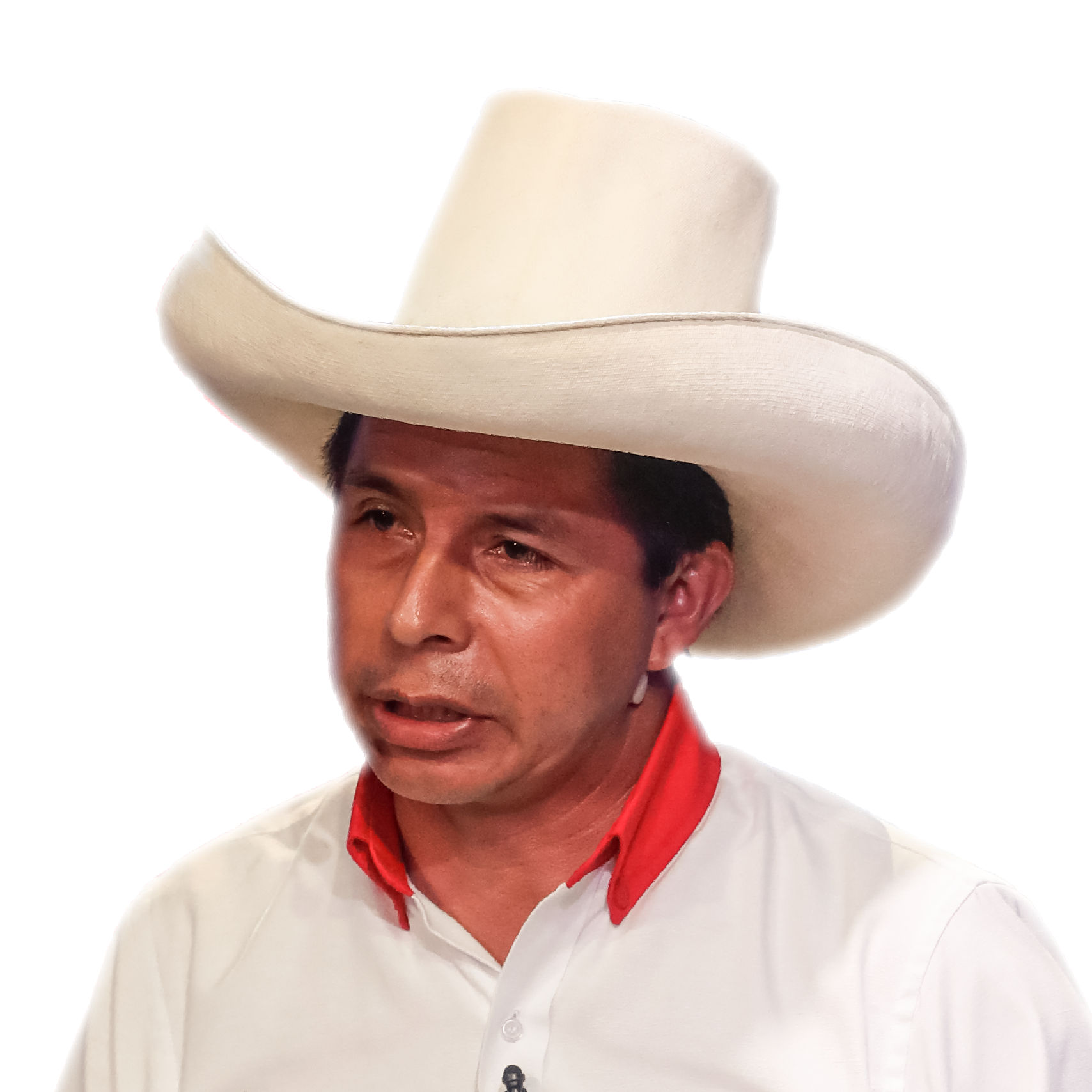

HOW HE GOT HERE

The election’s biggest surprise, Castillo surged in the final days before the first round of Peru’s election, representing a far-left political party that describes itself as Marxist and Leninist. Hailing from the northern Cajamarca region, Castillo was an elementary school teacher and teachers’ union activist before entering politics. He rose to prominence by leading a national teachers’ strike for three months in 2017 to demand higher salaries. This is Castillo’s first run for the presidency, following a failed mayoral campaign in 2002.

WHY HE MIGHT WIN

Castillo represents a radical shift from Peru’s political and economic status quo at a time when recurrent political crises and a mismanaged pandemic have left voters disillusioned with the powers that be. Campaigning on horseback and wearing a cowboy hat to presidential debates, Castillo has a man-of-the-people image and appeals to rural interests that feel excluded by the Lima establishment. He is likely to benefit from the polarizing nature of his competitor in the second round, Keiko Fujimori, who spent much of the past two years in pre-trial detention for alleged corruption.

WHY HE MIGHT LOSE

Bloody conflict with far-left Shining Path terrorist group in the 1980s and 1990s left Peru with deep scars and a lasting stigma against leftist political projects. He has made statements – like that Venezuela’s government is democratic – that could scare many voters.

WHO SUPPORTS HIM

Castillo has support from anti-establishment voters across the country, but largely from Peru’s rural highlands. In the south, he was able to peel off votes from leftist competitors Verónika Mendoza and Yohny Lescano. He has garnered support among teachers, one of Peru’s biggest professions, who number at half a million nationwide. Supporting education is a key part of his platform – Castillo has even taken to carrying around a large pencil (also his party’s symbol) on the campaign trail.

WHAT HE WOULD DO

A critic of what he has dubbed Peru’s “neoliberal” economic model, Castillo has stated he would promote an “economy for the people with markets,” which would likely follow protectionist policies. On April 22, Castillo walked back recent promises to nationalize several strategic industries, including hydropower, oil and gas, and mining, and he wants to spend 10% of GDP on both education and healthcare. Castillo has stated he will rewrite the constitution, vowing to dissolve Congress if it opposes this process. A social conservative, he opposes legalizing gay marriage, abortion or euthanasia.

IDEOLOGY

Keiko

Fujimori

45, former congresswoman

Popular Force

“I’m affirming my commitment to move ahead, with my father’s support.”

HOW SHE GOT HERE

Fujimori is the daughter of former President Alberto Fujimori, who is serving a 25-year prison sentence for human rights violations during his 1990-2000 government. She narrowly lost in the second round of the 2011 and 2016 presidential elections. Fujimori has been held twice in pre-trial detention related to alleged laundering of illegal campaign donations from Odebrecht. An investigation is ongoing, but at the time of publication, her candidacy was moving forward.

WHY SHE MIGHT WIN

Fujimori has a high level of name recognition. Some voters remember her father as a leader who oversaw important pro-business reforms and improved the standard of living.

WHY SHE MIGHT LOSE

Fujimori has the highest negative ratings among the candidates. Many associate her with authoritarianism during her father’s rule, as well as corruption. Support for her waned after a public confrontation in 2018 with her brother Kenji over an attempted vote-buying scheme. On March 11, prosecutors charged Fujimori with obstruction of justice, money laundering and organized crime related to alleged illegal campaign financing from Odebrecht and requested a prison sentence of 30 years and 10 months, as well as the dissolution of Popular Force.

WHO SUPPORTS HER

There is still a loyal pro-Fujimori electoral base among lower-income and more conservative voters. Alleged illegal campaign financing, as well as investigations into undeclared campaign donations from CONFIEP, the main business group that once backed her, eroded much of the support Fujimori had in private sector.

WHAT SHE WOULD DO

In addition to freeing her father from prison, Fujimori would likely pursue the market-friendly economic policies she has followed throughout her political career. She favors mano dura security policies, and has stated that Peru needs a “demodura”, which she defined not as a dictatorship, but as a “hard democracy”.

IDEOLOGY

Rafael

López Aliaga

60, businessman

Popular Renovation

“This is the last free election in Peru. If we don’t do well, this will be Venezuela or Cuba, mark my words.”

HOW HE GOT HERE

López Aliaga came to prominence in the business world, working for Citibank and founding PeruVal, a brokerage firm, before later becoming involved in the hotel and train industries. He served as a Lima city councilor from 2007 to 2010 and made an unsuccessful congressional bid in 2011 with the National Solidarity Party. A longtime member of that party, he became its president in 2020 and renamed it Popular Renovation while changing its color to light blue, which is associated with the pro-life movement.

WHY HE MIGHT WIN

López Aliaga is positioning himself as an ultra-conservative political outsider, and his candidacy could appeal to the private sector and to Peruvians who may have supported Keiko Fujimori in the past. He has attracted widespread media attention for his criticism of euthanasia, reproductive rights and immigrants. The coverage of his comments partially accounts for his rise in the polls.

WHY HE MIGHT LOSE

Some observers have dubbed López Aliaga the “Peruvian Bolsonaro,” but he has rejected the comparison, calling the Brazilian president “extremely intolerant.” Still, his statements, such as his assertion that President Francisco Sagasti’s government was committing “genocide” by not allowing private companies to import COVID-19 vaccines, may prove too extreme even for some voters on the right.

WHO SUPPORTS HIM

His supporters include higher-income voters, the business community and socially conservative Catholics and Christians. López Aliaga’s supporters are concentrated in Lima, and his base skews male.

WHAT HE WOULD DO

López Aliaga wants to attract private investment to tap Peru’s lithium deposits. A member of Opus Dei, he opposes abortion in all cases and has criticized what he has called the “gender agenda”. He is in favor of life imprisonment for corrupt public officials, and said he would expel Odebrecht from Peru. López Aliaga has also promised to reduce the size of government by closing nine ministries and lowering salaries for congressmen.

IDEOLOGY

Hernando

de Soto

79, economist and think tank president

Country Advancing

“I represent popular capitalism. I know how to create the conditions so that poor people can access mechanisms to grow.”

HOW HE GOT HERE

An internationally recognized economist known for his advocacy of private property and the free market, De Soto rose in the final weeks of the campaign as other frontrunners fizzled out in the spotlight. De Soto is running for president for the first time, but he’s not new to politics. A former director of Peru’s Central Bank, he was a key economic advisor to former President Alberto Fujimori, and his ideas around property rights and deregulation are credited with helping stabilize Peru’s economy and weaken the Shining Path terrorist group. He also advised and endorsed Keiko Fujimori’s 2011 and 2016 presidential runs. Currently, De Soto is president of the Institute for Liberty and Democracy, a think tank he founded in 1981.

WHY HE MIGHT WIN

His message of eradicating labor informality may resonate in a country where 75% of the labor force is informal, and where informality’s impact became starkly clear during the pandemic. For some voters, De Soto stands out as a competent alternative in a field of populist firebrands. If he makes the runoff with a leftist like Mendoza or Lescano, De Soto will benefit from a decades-long anti-leftist stigma.

WHY HE MIGHT LOSE

He’s running with a small party to which he has few ties. His candidate for second vice president is not well-known, which could make voters think twice in a country where three presidents have resigned or been impeached in the past four years. His ties to Fujimori and other controversial leaders – he advised Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi and Russia’s Vladimir Putin, among others – may alienate some voters.

WHO SUPPORTS HIM

Lima’s elite and the business class. De Soto, whose inner circle includes former high-level figures from Fujimori’s government, appeals to some voters who might be nostalgic for the reforms of the 1990s without the baggage and corruption of Fujimori.

WHAT HE WOULD DO

He’s largely status quo on economic issues and has said he wouldn’t “waste time” on changing Peru’s 1993 constitution, which incorporates many of the policies he advocated for. Some of De Soto’s statements, like his promise that he “won’t let delinquents or the poor from other countries enter (Peru),” have been criticized as xenophobic. He is an advocate of allowing the private sector to purchase and distribute vaccines.

IDEOLOGY

Yonhy

Lescano

61, former congressman

Popular Action

“PPK, Martín Vizcarra and Manuel Merino all betrayed the public.”

HOW HE GOT HERE

Lescano trained as a lawyer, taught law and hosted a radio show offering legal advice in his hometown of Puno in southern Peru before he was elected to Congress in 2001. He served for four terms, representing Puno and Lima twice each, leaving Congress in 2019.

WHY HE MIGHT WIN

Lescano’s long career in Congress and association with an established political party have earned him high name recognition. He has distanced himself from fellow Popular Action congressman Manuel Merino, who held Peru’s presidency for less than a week in November 2020 following the impeachment of former President Martín Vizcarra, in what some observers described as a coup d’état. Lescano is a center-leftist who is both socially conservative and economically progressive.

WHY HE MIGHT LOSE

As the candidate for Popular Action, Lescano’s association with Merino could haunt him. Lescano may lose voters on the left to Verónika Mendoza if her campaign gains traction. Critics have labeled him a populist, and his critiques of the private sector could scare investors. Following an accusation of sexual harassment in 2019, the congressional ethics committee suspended Lescano for 120 days. The case was shelved, and Lescano claimed the alleged victim’s evidence was fabricated.

WHO SUPPORTS HIM

Lescano’s support base is in southern Peru, a region that tends to vote for the left. His candidacy stands to attract fellow social conservatives who want more economic aid from the state, as well as voters seeking a centrist option.

WHAT HE WOULD DO

Lescano is known for his efforts to defend consumers’ rights and expand the redistribution of state resources. He has spoken about the need to “deglobalize” Peru’s economy and strengthen domestic production, but has promised that he would not nationalize any company. Lescano favors rewriting Peru’s constitution to more equitably manage extractive industries, and has spoken out against continuing the controversial Tía María mining project. He is against expanding abortion rights and supports civil unions, but not same-sex marriage.

IDEOLOGY

Verónika

Mendoza

39, former congresswoman

New Peru

“We need to get rid of the entire traditional political class. They should all go.”

HOW SHE GOT HERE

Mendoza is running for president after finishing third in 2016 with 18% of the vote. She served in Congress from 2011 to 2016. An anthropologist by training, Mendoza speaks Quechua and hails from Cuzco. Formerly a member of President Ollanta Humala’s Nationalist Party, she broke with Humala and left the party in 2012.

WHY SHE MIGHT WIN

Mendoza is one of the few leading candidates who is not from Lima, which could appeal to voters in the country’s interior. Many regard her as honest and transparent. In one of the countries hit hardest by the pandemic, Mendoza’s plans for social policies to address inequality could resonate.

WHY SHE MIGHT LOSE

Her leftist views could alienate voters in a country still haunted by the bloody legacy of the leftist Shining Path terrorist group. Center-leftist Yonhy Lescano is rising in the polls, and he may capture votes that would have otherwise gone to Mendoza.

WHO SUPPORTS HER

Mendoza’s base is in southern Peru, especially in cities like Cuzco, Arequipa and Puno. While she has struggled to build a united leftist coalition, she is the only socially progressive leftist among the leading candidates.

WHAT SHE WOULD DO

Mendoza seeks to implement progressive reforms in taxes, healthcare and the environment, as well as a “second agrarian reform” to support a sector that, according to her, has been “abandoned” by the state. She has announced that within the first year of her term, she would increase public investment by 2% of national GDP to close infrastructure gaps and create jobs. A key part of Mendoza’s platform is replacing the constitution. She has stated that Peru needs a new founding document to give citizens a greater say in their government, which is controlled by the political class.

IDEOLOGY

Daniel

Urresti

64, congressman and former interior minister and general

We Can Peru

“As long as criminals are on the street, you will continue to see me.”

HOW HE GOT HERE

A retired army general, Urresti served as the interior minister under President Ollanta Humala from 2014 to 2015. He ran for president in 2016, but Humala’s party pulled Urresti’s candidacy. After mounting a failed bid for the mayoralty of Lima in 2018, he served as the head of public safety in a municipality on Lima’s outskirts. Urresti won a congressional seat in January 2020.

WHY HE MIGHT WIN

Best known for his hardline stance on crime, Urresti appeals to concerns over security, which remain heightened despite crime levels being stable throughout 2020. He makes frequent media appearances and has a confrontational personality and a reputation for telling it like it is, which is popular among some.

WHY HE MIGHT LOSE

Urresti is a polarizing figure who is not well known outside of Lima, and apart from being tough on crime, he has not taken many strong policy stances. He was charged with ordering the 1988 murder of a journalist and faces a retrial relating to the case after the Supreme Court overruled a 2018 decision that cleared him of the crime. Urresti’s candidacy was in question after an elections board declared valid a complaint that claimed his party did not abide by regulations. However, on Feb. 18 an elections authority ruled that Urresti could remain a candidate.

WHO SUPPORTS HIM

Most of his supporters are in Lima. Urresti is ideologically fluid, and his populism holds appeal for anti-establishment as well as anti-Fujimori voters.

WHAT HE WOULD DO

He has promised to fight corruption and crime, and recently introduced legislation to prevent the resale of stolen goods. Urresti has also signaled he would permit continued pension withdrawals, but has been otherwise vague on his economic policies.

IDEOLOGY

George

Forsyth

38, former mayor and professional soccer player

National Victory

“We want a new generation of politician. The corruption is killing us.”

HOW HE GOT HERE

A national champion soccer goalie who also played briefly for Peru’s national team, as well as a business owner and reality TV contestant, Forsyth used his celebrity to enter politics in 2010 as a council member in Lima’s working-class La Victoria municipality. After his election as La Victoria’s mayor in 2018, Forsyth gained notoriety for his work to “clean up” the municipality, using both sports — he moved the mayor’s office to an abandoned sports complex — and heavy-handed policies, like police evictions of informal workers.

WHY HE MIGHT WIN

Thanks to his regular media presence, he is recognized by many. He is a fresh face who sells himself as a new generation of politician at a time of widespread frustration with the political class, and his limited experience in politics means he has less baggage than other candidates.

WHY HE MIGHT LOSE

After Forsyth resigned as mayor to run for president, his replacement said residents “felt used politically.” His inexperience and vague platform may also turn voters off. On Feb. 25, electoral authorities declared Forsyth’s candidacy invalid for a second time, citing discrepancies over declared income sources. Forsyth can appeal the decision.

WHO SUPPORTS HIM

Forsyth does not have a clearly defined ideological base, but polls suggest that his supporters skew younger, more urban, wealthier and more female.

WHAT HE WOULD DO

Forsyth is pro-business, anti-corruption, and tough on crime, but he hasn’t gone into much detail on policy. He said his decision to run for a conservative party was based on its record of being clean of corruption rather than for its ideology. Forsyth called for amending the constitution to declare corruption a crime against humanity.

IDEOLOGY

Julio

Guzmán

50, former secretary-general of the presidential cabinet

Purple Party

“The pandemic has created a lot of fear, and populists want to take advantage.”

HOW HE GOT HERE

An economist and Ph.D. in public policy, Guzmán spent a decade at the Inter-American Development Bank before working as a deputy minister and cabinet chief for former President Ollanta Humala. Guzmán ran for president in 2016, climbing to second place in polls before his candidacy was disqualified on a controversial technicality. Later that year he launched the Purple Party.

WHY HE MIGHT WIN

Following former President Martín Vizcarra’s impeachment, Guzmán played a prominent role in opposing Manuel Merino’s government. He is a technocrat whose experience in government may appeal to voters.

WHY HE MIGHT LOSE

Some see Guzmán as lacking in charisma, and his centrist views could be perceived as an aversion to taking firm stances. Past scandals may also hurt his chances. Guzmán issued an apology after a case of infidelity emerged in January 2020. In August, authorities opened an investigation into allegations that his 2016 campaign accepted an illegal $400,000 donation from Odebrecht. Guzmán’s fellow Purple Party member, President Francisco Sagasti, has been blamed for mismanagement of the pandemic, which could affect Guzmán’s prospects.

WHO SUPPORTS HIM

Political analysts describe his supporters as centrist, with higher levels of education.

WHAT HE WOULD DO

Guzmán has argued that Peru should lessen its dependence on exports by diversifying its economy. He says the state should combat monopolies “so that the market can be free.” Guzmán has also called for reforms to increase tax revenues and transparency in public contracts. If elected, Guzmán stated that he would consider holding a referendum on whether to write a new constitution.

IDEOLOGY