BOGOTÁ — It’s the region where Colombian President Gustavo Petro was born and the one that catapulted him to the presidency in 2022. Petro beat his opponent by 700,000 votes—and that is the number by which his votes in the Caribbean rose from the first to the second round, with those in Barranquilla growing by 40%. Yet the Caribbean coast is also the source of two ongoing scandals threatening his political future. A zone in flux, its largest city is an ambivalent success story—and home to a powerful political family, aligned with the president’s right-of-center enemies, which looks destined for another victory in local elections on October 29.

Colombia’s Caribbean coast has long suffered from neglect. But the development of Barranquilla, its largest city, is in the process of remaking the region’s image. Through Alejandro “Alex” Char’s and his proteges’ time as mayors of the city since 2008, the nation’s “Golden Gate” has seen poverty reduction of 23% over a decade; the channelization of 67 km of streams that once menaced the city with flooding, dirt roads paved, health infrastructure improved through the modernization of 43 healthcare facilities, and the construction of a riverside pier along the Magdalena River with parks, a mall, and a convention center. Between 2010 and the end of Char’s second term in 2019, average wages in the city grew 74% compared with 39% in Bogotá. The port city of 1.2 million inhabitants, the country’s fourth largest, now boasts extraordinary investment figures that totaled $262 million in 2022, mostly aimed at comparably high value-added industries.

The boom has magnified the strength of the already powerful Char family, for whom Barranquilla serves as a political base. The patriarch of the family, Fuad, came to prominence as the owner of supermarket chain Olímpica. His own involvement in politics as senator and governor, paved the way for his son Arturo to become a senator for over a decade and reach the legislative body’s presidency. Alejandro, after a short time leading a construction company that won major national contracts, focused on municipal politics as two-time mayor of Barranquilla, until a presidential bid last year that ended in a primary defeat.

The Chars’ prominence has not been free from criticism: A recent book by journalist Laura Ardila presents evidence of misdeeds under their watch, while Arturo Char was arrested last month, accused of buying votes. Char has denied the allegations. According to Colombian media reports, Alejandro had a romantic affair with a central figure in the vote-buying case, raising questions about whether he will be drawn into the investigation. Alejandro has denied accusations of his involvement.

The Chars’ influence—primarily aligned with the right—has been increasingly felt at the national level in recent years, with close ties to President Juan Manuel Santos’s vice-presidential pick, Germán Vargas Lleras, and influencing ministerial picks in two previous administrations and seven senators in the current Congress.

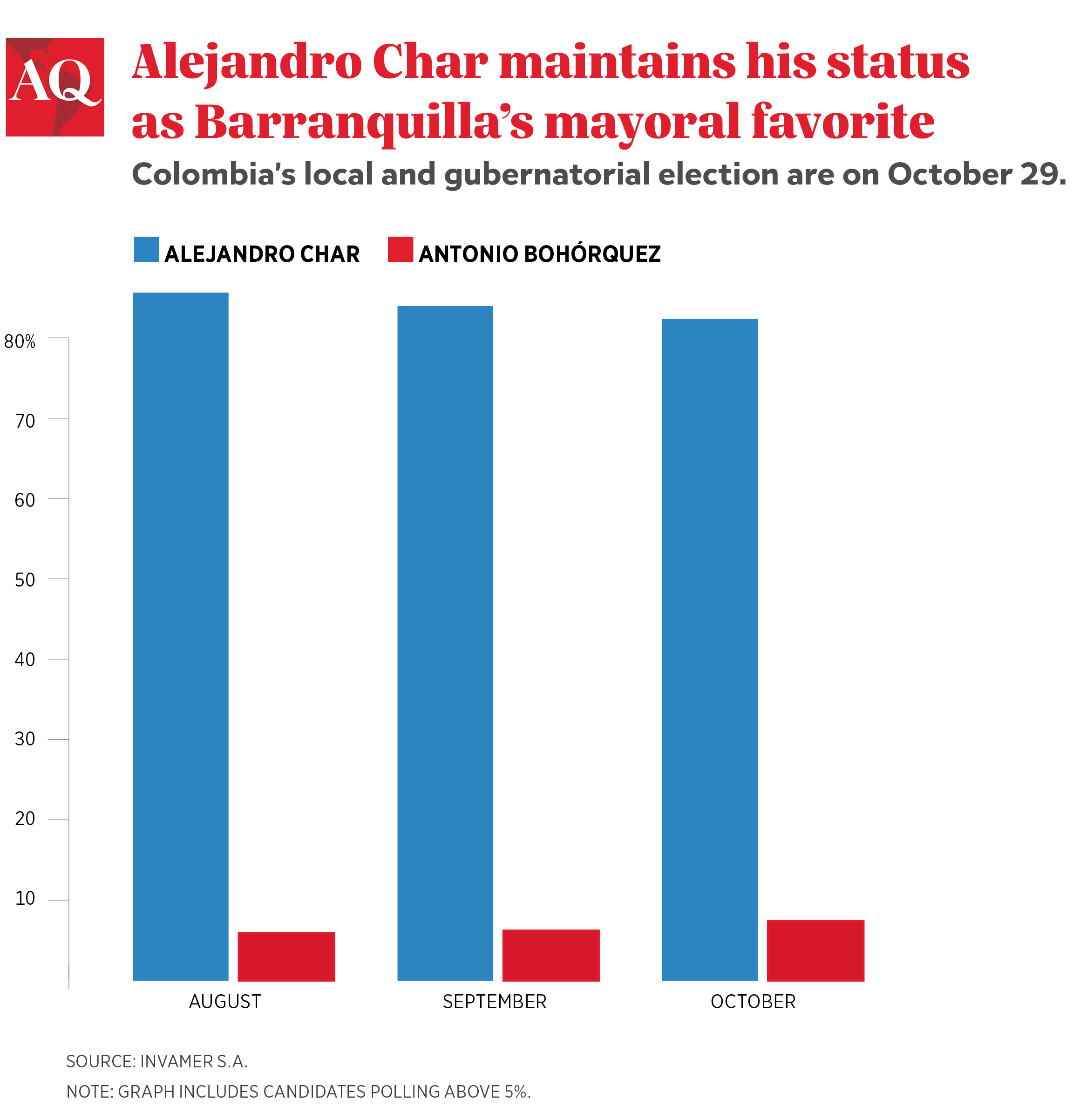

Arturo’s September arrest seems unlikely to affect the election: Alejandro’s poll numbers have not budged since then. The Office of the Attorney General, in charge of investigating civilians like Alejandro, has moved more slowly on the case than the Supreme Court, which investigated Alejandro’s brother due to his former status as a senator. The former body is controlled by an Iván Duque appointee, Francisco Barbosa, and is seen by some as dragging its feet on the case—but that may change in February when a Petro appointee comes into office.

Petro and the Caribbean

Underdeveloped and with some of the country’s highest informality rates, the Caribbean region’s demands for change became a powerful source of support for Petro’s campaign. But electoral support from the Caribbean may also have come at a price. Petro’s biggest ongoing political crisis features allegations of drug money entering the presidential campaign and stars Armando Benedetti, his campaign manager—a Barranquilla native—who was a key broker of the region’s support for the Pacto Histórico candidate. Meanwhile, the president’s oldest son Nicolás, until recently, a public official in the Caribbean, is accused of mismanaging funds during his father’s campaign last year. Petro has denied that his campaign received money from drug trafficking groups.

These scandals and an underperforming administration have led analysts to conclude that the October local elections, serving as an informal referendum on the president, will turn out unfavorably for him. Polls show that left-of-center candidates are trailing in the country’s major cities and, in most cases, by large margins. Being the Caribbean’s largest city, Barranquilla is no exception.

Political and publishing intrigue

The Char family’s power in Barranquilla and its surroundings is the subject of Laura Ardila’s, La Costa Nostra (“Our Coast,” a play on la cosa nostra, a term for the Sicilian mafia). The book was the occasion of a controversy in July, when the publisher stopped the presses at the last minute—according to Ardila, because of fears of legal action by the book’s subjects. Ardila published the book with independent publisher Rey Naranjo instead, but the incident demonstrated the chilling influence of power on journalistic inquiry.

Ardila’s book critically examines Barranquilla’s success story under the Char family. During his first term, as Ardila explains, Alejandro’s favorable relations with then-president Alvaro Uribe were crucial. Enjoying windfall gains from the commodities boom, Uribe’s coffers were full, which helped to fund projects and solve the city’s fiscal problems. Ardila argues the mayor’s administration relied on a system in which four contractors dominated the scene and, Ardila alleges, may have used the state to launder money. “The private contractor lends the state the money to execute the contract,” she writes, “and receives income from the public entity, and no one questions the origin of that capital.”

Even as the Char family faces potential setbacks in Colombian courts and investigative bodies, unwavering support for Alejandro Char in his attempt to lead Barranquilla for an unprecedented third term demonstrates that Barranquilleros continue to have a deep trust in the family’s public management.

Still, the city and the Caribbean region will continue to deal with public service access issues and economic hardship that both the left and right parties will vie to address, seeking to capitalize on its crucial electoral potential.

—

Rendon Vera is a researcher and freelance journalist based in Bogotá. He was previously a legislative assistant in Colombia’s House of Representatives.