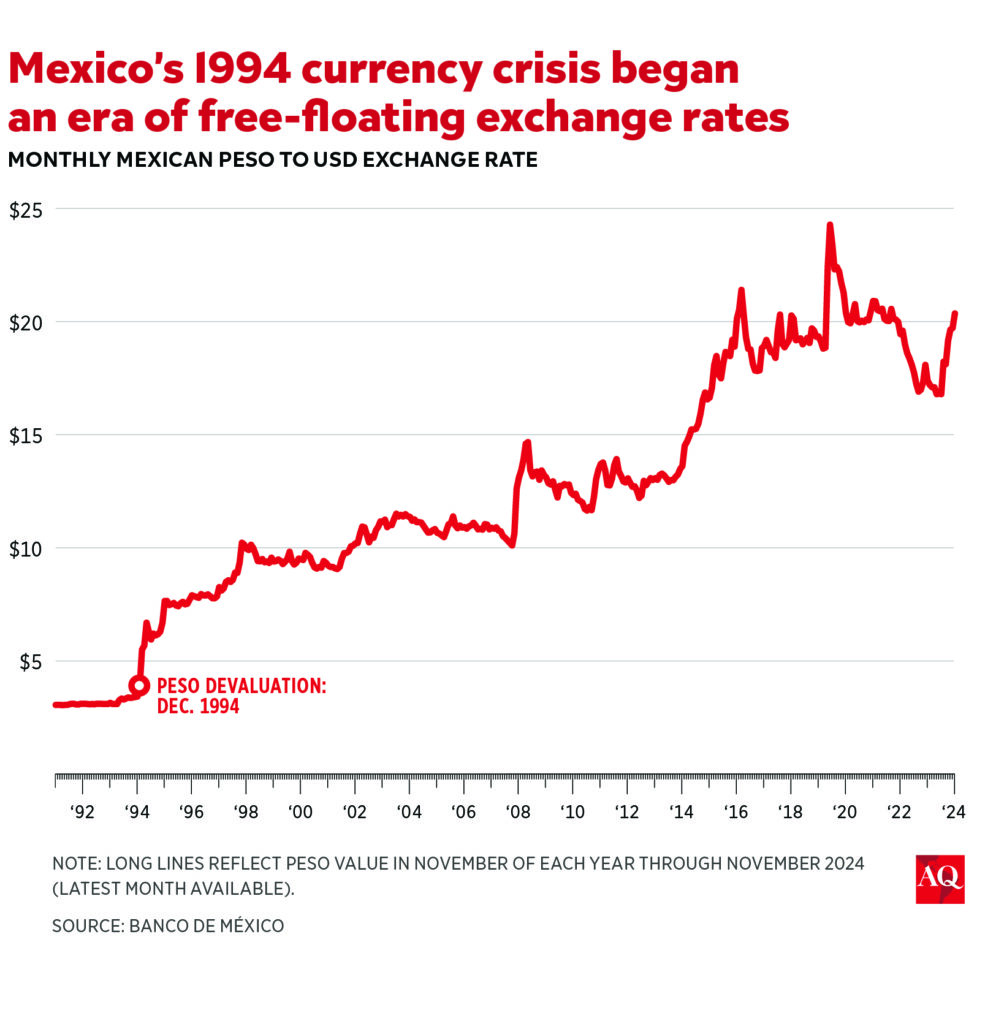

MEXICO CITY — On December 20, 1994, the recently inaugurated Ernesto Zedillo administration in Mexico announced a 15% devaluation of the Mexican peso against the dollar, unleashing what soon would be known as the “Tequila Crisis.”

The next year, Mexico’s economy contracted by a staggering 5.9%, while unemployment almost doubled, reaching 7.1%, its highest reading ever. The crisis left its mark on the rest of the 1990s in Mexico, badly damaging Zedillo’s popularity and contributing to the PRI’s loss of the presidency, for the first time in more than 70 years, in 2000.

At the time, Robert Rubin, about to be named U.S. Treasury Secretary, called the episode the “first crisis of the 21st century.” Now, 30 years later, his comment seems prescient: The crisis was an early illustration of the risks of financial liberalization—but also the advantages of a free-floating currency. With a rocky road ahead when it comes to the all-important economic relationship with the U.S., some of the legacies of three decades ago could actually help Mexico navigate this new challenge.

How the crisis took shape

Like many other economic crises, the TC was at its core a problem of excessive leverage by the private sector. After years of large fiscal deficits and financial repression, the local saving rate in Mexico was too low to finance strong borrowing needs by the private sector. Mexico under Carlos Salinas de Gortari, Zedillo’s predecessor, attempted to address this problem by providing access to foreign savings, via financial liberalization. The country was thus the first of several emerging markets attempting to defy the so-called “Feldstein-Horioka paradox” (national rates of savings and investment cannot differ substantially), by posting an increasing current account deficit which, by 1994, had reached 7.7% of the nation’s gross domestic product.

Such a level of indebtedness with the rest of the world is particularly worrisome when you target a certain FX value. This was the case of Mexico at the time, with its “crawling peg” system. This allowed the Mexican currency to float against the dollar within a range whose upper boundary was revised upwards daily, thus providing room for a “managed” nominal depreciation of the peso. The question was what might happen when market conditions required a faster pace of slippage than that allowed by the prevailing range.

As major political shocks took place throughout 1994, including the shocking assassination of PRI presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio, Mexico tried to reassure jittery investors by offering them to cover their FX risk via Tesobonos, or bonds denominated in pesos but nonetheless linked to the value of exchange rate of the dollar. Issuance of this type of security rose from $1.8 billion in 1993 to $16.1 billion during 1994. The problem that would eventually land on Rubin’s desk was that, as peso devaluation did happen, the nominal value of Tesobonos entered into a vicious spiral. Investors would use their cash from Tesobonos sales to buy dollars, thus leading to more peso devaluation, which in turn would increase the nominal value of upcoming Tesobonos maturities, further reinforcing the urge to buy more dollars, and so on. It would take a major package assembled by the U.S. Treasury, the IMF and Canada worth about $40 billion, to eventually cut short these perverse dynamics.

Stumbling into a currency float

This leads to the second innovative result of the TC. Prevailing exchange-rate arrangements among emerging markets at the time favored some form of intervention, including attempts to fix the exchange rate in order to provide a “nominal anchor,” able to pull down local inflation levels. In the aftermath of the TC however, Mexico could not afford any other option but to let its currency float. We stumbled into a free-floating exchange-rate regime, but with the benefit of hindsight, it turned out to be a blessing. By 2022, the IMF reported that 65 member countries were opting for a floating currency.

I first realized the potential advantages of a free-floating peso while finishing my Ph.D. dissertation around the time of the TC. My aim was to look at the effects of trade liberalization over the performance of Mexican industrial sectors. Yet when I incorporated into my simulations a much weaker peso in real terms, I saw that imports would increase modestly in spite of the disappearance of tariffs, while exports would grow substantially. And indeed, as Mexico had just joined NAFTA with a significantly undervalued currency in real terms (because of the TC), the rebound in activity proved to be surprisingly fast.

Implications for the U.S.-Mexico relationship today

That brings us to our own, uncertain times. Mexico’s current account deficit has averaged a reasonable -1.1 % of GDP so far this decade. However, our relationship with the U.S. is far more complicated than in the heyday of NAFTA. Trade policy by the coming Trump administration is set out to take a more transactional and confrontational approach, with the threat of tariffs likely to be a constant feature in each item of the complex bilateral agenda.

Against this backdrop, the free-floating peso can help a lot.

U.S. tariffs on imports of Mexico implies higher costs for the U.S. consumer (i.e. inflation) under the “small country assumption,” the theory that a country cannot alter its terms of trade. On this side of the border, though, the U.S. does not look small at all: It accounts for 83.7% of total Mexican exports. U.S. tariffs can influence bilateral terms of trade by making goods from Mexico cheaper, via a depreciation of the real exchange rate.

In order to achieve this real exchange rate depreciation, Mexico will need higher nominal values for the dollar-peso exchange rate that do not create significant pass-through effects on local inflation. In other words, we should be prepared to see wild fluctuations in the exchange-rate market—just like the ones the IMF documented during the first Trump administration—with Mexico’s central bank, Banxico, focused on its single mandate of price stability to ensure that overall inflation levels do not change.

Under these conditions, export industries in Mexico would remain competitive in spite of tariffs, but U.S. producers catering to the Mexican market would struggle, as their goods would become more expensive in pesos. Under these conditions, a tariff can end up affecting those it claims to protect.

Thirty years ago, the Mexican peso was the problem. In the near future, it can be part of the solution, provided we let it do its work.