Part of a continuing series on how Latin America can overcome a decade of slow economic growth.

Leer en español | Ler em português

This was supposed to be “the Latin American decade.”

When it started in 2010, the region was still riding high from the commodities boom. Its prospects seemed brighter than any point since at least the early 1970s. Yes, Latin America is famous for its ups and downs, its cycles of high hope followed by disappointment. But even some of the cynical among us believed this time was different. Improving education levels, a unique “window of demographic opportunity,” greater access to mobile phones and other revolutionary technology, China’s continued rise, healthy fiscal outlooks and the nearly universal spread of democracy – all these were cited as factors that would continue to make Latin America a star performer in the years ahead.

Unfortunately, it hasn’t turned out that way.

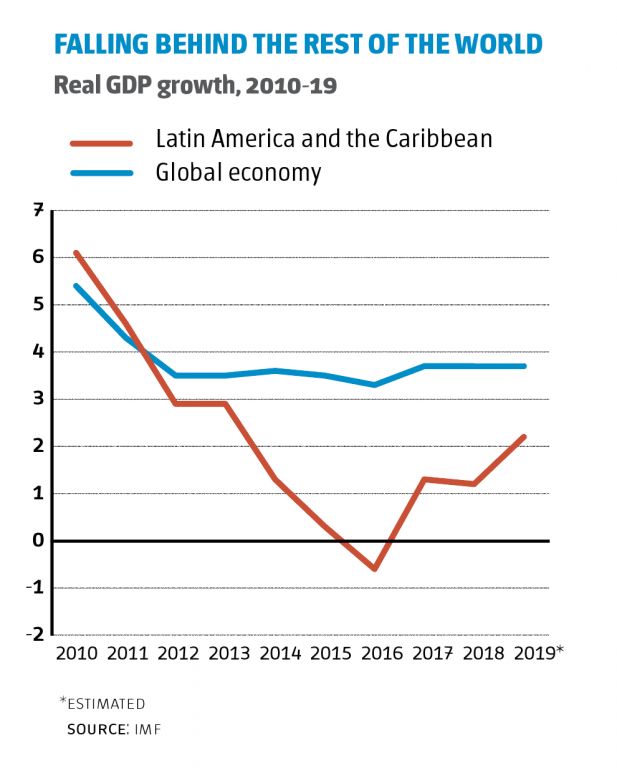

Instead of thriving, Latin America has fallen badly behind the rest of the world. Barring a last-minute miracle, the region will average economic growth of just 2.2% during the 2010s, well below the 3.8% global average – and lagging emerging market peers such as Emerging and Developing Asia (7.1%), Sub-Saharan Africa (4.1%) and the Middle East and North Africa (3.3%). Poverty has risen in many countries, along with unemployment – and a worrying dissatisfaction with democracy. Of course, some places have performed better than others. But the general story has been one of disappointment (Mexico, Colombia, Argentina), collapse (Brazil) or downright tragedy (Venezuela).

For all the differences among Latin American countries, you could say each decade has had a broadly unifying image or identity. The 1970s are widely remembered as an era of military coups and juntas, while the 1980s was a “lost decade” of debt crises. The 1990s was the “Washington Consensus.” The 2000s was the commodities boom. And the 2010s may be remembered as “The Hangover” – a painful period in which Latin America struggled to recover from the excesses and unrealistic expectations of the previous decade.

How did we get here? When did the party start to rage out of control? How can the region get back on its feet, and ensure the 2020s aren’t just as painful? To shed some light, I revisited some of the most optimistic forecasts from the beginning of the decade, and spoke with the authors to ask what they believe went wrong. I reviewed several comprehensive recent studies that assess why the region isn’t growing faster. And there’s good news: While everyone may have their own suggested remedy for hangovers in real life, there’s actually some consensus around what’s needed to cure this one.

How the Problem Started

As fate would have it, I moved to São Paulo in mid-2010, right as Brazil and other countries were reaching the peak of their boom. Brazil’s economy would grow 7.6% that year, the World Cup and Olympics were just around the corner, and all the talk was of a country whose “future had finally arrived.” Roads were packed, as thousands of new cars hit the streets every day. Airplanes were full of first-time fliers – you could often distinguish them by their sheepish smiles as they searched for their seats. Flat-screen TVs, washing machines and refrigerators flew off the shelves, and restaurants were packed. It was a truly amazing and uplifting sight, especially for an American who had just slogged through the Great Recession.

But I remember one question kept nagging at me:

“Where are all the cranes?”

Given the historic nature of the boom, I naively expected to find a country under construction – investing like crazy in new roads, ports, schools and public transport. But this was not the case, and here Brazil was not alone. While investment throughout Latin America did rise during the 2000s as a percentage of GDP, it remained lower than any other major region but Sub-Saharan Africa, according to a 2018 study by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). You could say, with only some exaggeration, that Latin America spent the windfall on new cars instead of new roads – on consumption rather than investment.

That certainly explained the horrendous traffic – and it was also a main reason the 2010s have been so disappointing. Governments and consumers alike believed the good times would last longer than they did. So they passed up a golden opportunity to make lasting improvements in productivity – which could have kept economies growing once commodities prices fell. “Unfortunately I think it’s proof that in Latin America we have tended to manage crises better than opportunities,” the IDB’s president, Luis Alberto Moreno, told me. “There was a lot of overreach.”

Moreno may have been the first to popularize the notion of a “Latin American decade” – the title of an op-ed he wrote in July 2010 for the Financial Times. The idea was touted by others from the British ad man Martin Sorrell to Colombia’s former President Juan Manuel Santos. Even in some countries where the commodities boom was never really a thing – north of, say, Costa Rica – hopes were also high. Enrique Peña Nieto took office in Mexico in 2012 vowing to achieve 6% annual growth; not everybody laughed. A 2010 cover of The Economist proclaimed that Latin America was “Nobody’s Backyard” – and called for a “new attitude” about the region “north of the Rio Grande.”

In truth, all of these optimistic treatises were full of “ifs.” The first potential pratfall Moreno cited in his FT article was the region’s fiscal situation, which began the 2010s in strong shape. Regionwide, fiscal deficits were averaging 2.3% of GDP, and total public debt was roughly half that of Europe and the United States. This macroeconomic stability was itself a major conquest, thanks to the tough budget reforms and privatizations many countries embarked on in the 1980s and 1990s.

Sadly, this was the other big area where things fell apart. When commodities prices started to drop in earnest in 2012-13, those governments that did the best job adjusting to the “new normal” tended to escape the worst economic effects. Colombia, Chile and Peru never allowed their fiscal deficits to exceed about 3% of GDP; perhaps as a result, their economies outperformed the Latin American average every single year this decade. In contrast, Brazil’s government cut taxes and abandoned its fiscal goals in a doomed attempt to keep the good times rolling; the deficit bottomed out at 9% of GDP in 2015, and the ensuing recession turned into its worst on record. Argentina’s deficit has reached 6% in recent years. Venezuela’s case is so extreme it must almost be treated separately, but the underlying issue is the same: a spendthrift government that thought the bonanza would last forever.

There is an ongoing debate among economists about whether the region’s fiscal troubles have been a cause or symptom of the recent malaise. But there is no doubt the issue has dominated policymakers’ attention – and sabotaged many big dreams. Mauricio Cárdenas, then of the Brookings Institution, published an article in 2011 entitled “Latin America’s Decade: A Once in a Lifetime Opportunity.” A year later, he was appointed Colombia’s finance minister – at a time when prices for oil, its main export, plummeted so fast that revenues fell 51% in one year alone.

“For four or five years, we really had to focus on adjustment, adjustment – making sure there was not a major crisis,” Cárdenas told me. “So it was not really a conversation about the future – a lot of that unfortunately got lost.”

This was all the backdrop for an increasingly sour public mood. Just 16% of Latin Americans now say they are “satisfied” with their country’s economy, half the level of 2010. Latin America has gone from a region where incumbents (or their handpicked successors) almost always won elections to a place where seemingly every vote is about the most extreme change possible. Even the decade’s biggest achievement – the anti-corruption movement that has sent previously untouchable politicians and business leaders to prison from Guatemala to Peru – can be attributed at least in part to the economic malaise. Numerous judges and prosecutors have told me that, had the public been happier, there might never have been the widespread clamor for justice that helped make their cases possible.

Looking Ahead

The good news about hangovers is they’re not the end of the world – and they’re also curable.

Even at 2.2%, economic growth this decade will have been better than the 1.8% expansion Latin America averaged from 1983 to 2000. Many gains from the boom remain intact; poverty has remained stable this decade at around 30% (down from 45% in 2002), while inequality has continued to fall, albeit at a lesser pace, according to the UN agency CEPAL. Even the fiscal situation could be worse: The region’s public sector gross debt will close the decade at about 65% of GDP, according to the International Monetary Fund. That’s up a worrying 10 percentage points since 2015, but there is still time to avert disaster. New governments in Brazil and Colombia seem focused on defusing the fiscal time bomb; the outlook in Argentina and Mexico is less certain.

The bad news is that the world has moved ahead – and challenges like automation and artificial intelligence are looming large. Latin America is rapidly getting older, making reforms to pension systems particularly urgent. Meanwhile, middle classes that have tasted prosperity, and can see how the other half lives on Instagram, are going to demand ever more – and lash out if they don’t get it. “I worry about a misalignment between expectations and reality,” Cárdenas said. “In many countries, the debate doesn’t really seem to be about the issues that matter.”

That could be because the solutions are unglamorous, and not particularly new. For starters, pretty much everyone agrees that Latin America simply must find a way to invest more. The aforementioned IDB study found that if the region had invested as much and as efficiently as Emerging Asian countries over the last 50 years, Latin America would be about twice as rich as it is today. That may be the kind of alternate reality only economists fantasize about, but the message is clear enough.

A separate 2018 IMF study tried to assess the biggest obstacles to greater investment in Latin America, based on polling of business leaders and other data. In order of importance, the challenges were: Inefficient government bureaucracy, corruption, tax rates, policy instability and the quality of infrastructure. Thankfully, the outlook on several of these fronts is not bleak. The “Car Wash” probe and other investigations have raised hopes of a significant and lasting reduction in corruption; private-public partnerships are proving an effective tool for getting ports and highways built; several countries have undertaken a war against red tape. “The macro reforms have mostly been done,” said Susan Segal, CEO of AS/COA. “Now it’s time for the micro reforms that will make the business climate better.”

There are of course other obstacles to faster growth, from education to access to financing to the very real economic toll of inequality and violence. The IMF expects the next decade to start much like this one – with growth of just 2.5% in 2020. Meanwhile, there is a risk that the global economy will now slow down just as the region gets its act together. But part of the challenge will be learning lessons from the disappointments of the 2010s without getting too discouraged by them. “It’s always easy and safer to be negative about Latin America,” Michael Reid, the longtime regional editor for The Economist, told me. Maybe a more even keel, and a realistic set of expectations, is the best hangover cure of all.