Correction appended below.

When Javier Milei, Argentina’s newly elected libertarian lawmaker, raffled off his monthly stipend for the third time in mid-March, 2 million people signed up. That’s almost 5% of the country’s entire population. The lucky winner was 26-year-old Cecilia Agüero from Buenos Aires province, who said she would use the 350,000 pesos (about $1,800) to finish construction on her house.

For a while, it was tempting to dismiss Milei as a fringe figure who was prone to such publicity-grabbing stunts, but didn’t have a chance to break through Argentina’s entrenched political divide between the Peronist governing coalition and the center-right opposition. A professor of economics and radio host who proudly claims he “never” combs his unruly hair, Milei’s over-the-top persona made it easier to write him off: “I would rather cut my own arm off than raise taxes,” he said in 2020.

Argentina’s endless run-ins with multilateral lenders like the International Monetary Fund and its intricate array of capital controls can be solved easily, he says: just abolish the central bank and dollarize the economy. His catchphrase? “Long live liberty, goddammit!” After the killing of a shopkeeper in Buenos Aires during a robbery in November caused a public outcry, the minister of security said that “this happens in many places,” prompting Milei to call him a “son of a bitch” on Twitter.

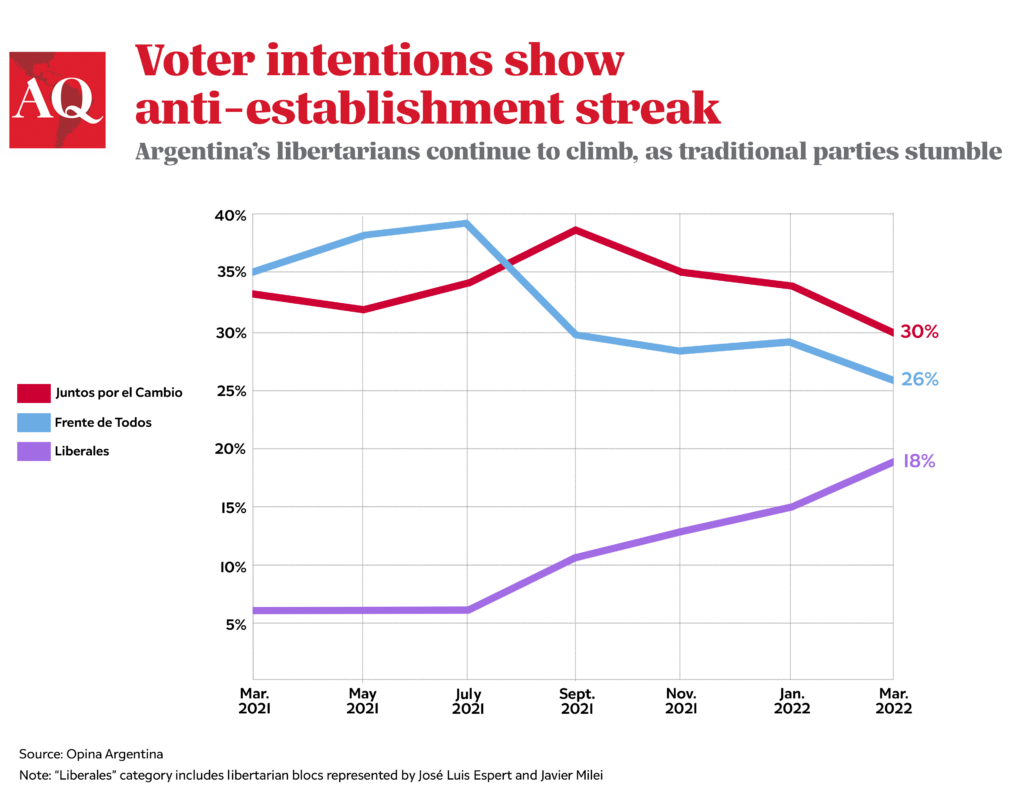

But Argentina’s political establishment isn’t laughing now. Milei and his libertarian allies took 17% of the vote in Buenos Aires in midterm elections last fall, helping deny the opposition the majority they wanted. With his libertarians now polling at 18%, Milei has declared he will run for president in 2023—and some analysts think he has a chance at victory.

Desperate for a third way

A casual observer might be surprised by the rise of libertarian ideas in a country long associated with Peronism and economic regulation. But the very bulk of the Argentine state makes it an easy target for libertarian critique. The most recent OECD data show the disproportionate size of Argentina’s public sector, which employs 17% of workers compared to Brazil’s and Mexico’s 12%. Tax revenues make up nearly 30% of Argentine GDP, compared to 21% in Chile and 16% in Mexico.

What’s more, consecutive administrations from both sides of Argentina’s political aisle have now failed to resolve the country’s economic dysfunction. Mauricio Macri, president from 2015 to 2019, sought to combat economic stagnation with free-market reforms, but struggled to make progress on stabilizing the currency—and drew criticism both from left-wing kirchnerists and his right flank. Milei’s ally (and possible running mate) José Luis Espert, a libertarian economist and longtime supporter of “shock therapy” for Argentina, famously described the Macri government as “kirchnerism with good manners.”

Alberto Fernández’s government, in office since 2019, has also struggled to address rising poverty and economic stagnation, and recently has seen its left flank threaten to break away. Through it all, Argentina’s private sector has remained anemic: As of 2020, out of 100 working-age Argentines, only 18% were employed in formal work in the private sector—the rest were either on welfare rolls, working informal jobs or in the public sector.

It’s clear why many Argentines want a third option and find compelling Milei’s denunciations of the country’s “political caste”—both governing Peronists and the traditional center-right opposition—which he says is riddled with “social democrats” who perpetuate failed statist policies.

Members of the Milei squad

Milei has disrupted the left–right age divide in Argentine politics, peeling a sizable chunk of Argentina’s youth away from left-wing and Peronist positions. “Until five or six years ago we thought that young people were kirchnerists by default,” said María Esperanza Casullo, a political scientist at the National University of Río Negro.

Milei’s often campy public presence and memorable catchphrases have a clear appeal to young millennials and Generation Z. In a segment aired on Argentine television in September, a young Milei supporter wearing a Guy Fawkes mask at a demonstration explained he left the Peronist movement “because they were all dirty. I want things to be clear and clean.”

Some have also noted that Milei’s public persona carries a whiff of Anglophilia—his Mod haircut and ’60s-style sideburns make him look like a singer in a Rolling Stones cover band, which in fact he was before setting out on a career as an economist. But as the Financial Times noted in November, “His admiration for Margaret Thatcher seems more risky in a country where memories of the 1982 Falklands war are still raw.”

Perhaps even more worrying to the left than his youth support is that Milei’s most passionate supporters aren’t wealthy. “His vote (has) a tendency to be larger among lower social classes,” says political scientist Sergio Morresi. A typical Milei supporter might be a shopkeeper or a precarious worker who isn’t dependent on state welfare aid—and resents those who are.

Milei may be, for the moment, the most prominent Latin American libertarian—but he isn’t the only one. In Guatemala, Gloria Álvarez has a popular radio show and garnered headlines when she tried running for president in 2019, only to be disqualified since she was 34 and the minimum age for the presidency is 40.

In Chile, a libertarian YouTuber named Johannes Kaiser won election as a federal deputy in 2021. Brazil saw the emergence of free-market movements like Kim Kataguiri’s Free Brazil Movement during Dilma Rousseff’s second term in office (2015–2016), but these have stagnated since the rise of Jair Bolsonaro, who despite the presence of his Chicago-educated economy minister Paulo Guedes is not a convinced disciple of the free market.

When it comes to cultural matters, Milei is often conservative. Against quotas for underrepresented groups and the government’s official use of “inclusive language,” Milei commented last October in response to a question about unequal wages for men and women: “If women were paid less, businesses would be full of them!” Milei wants abortion to be permitted only when the mother’s life is in danger. He received praise from defeated Chilean presidential candidate José Antonio Kast and signed a document circulated by the Spanish far-right party Vox accusing left-wing groups like the Foro de São Paulo of engineering a criminal project to rob Latin America of liberty. “Vox has very little do to with libertarianism,” said Daniel Raisbeck, a prominent Colombian libertarian. “I don’t think it makes a lot of sense.”

What real prospects do Milei and his party have? It all depends on the performance of the current governing coalition. In the event of a 2003-style Peronist splintering, with multiple candidates running for the presidency under the Peronist umbrella, Milei could stand a real chance of making a runoff. But if the governing coalition stays together, his influence is more likely to be through increased representation in Congress and through appointments by a potential victorious Juntos por el Cambio coalition government, similarly to the UCD party, which took third place in 1989 elections but later served an outsized role in masterminding neoliberal reforms under Carlos Menem.

What is clear is that Milei has already had a significant impact on Argentine political discourse, in a way perhaps broadly analogous to that of Bolsonaro in Brazil. On topics like opposition to contemporary feminism or left-wing cultural positions, “these were things you couldn’t say (in public) before the emergence of Milei,” said Sergio Morresi, a political scientist. “Now they are visible.”

This article was updated on April 11 to correct the exchange rate between dollars and Argentine pesos.