This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on the 2024 U.S. presidential election and its impact on Latin America

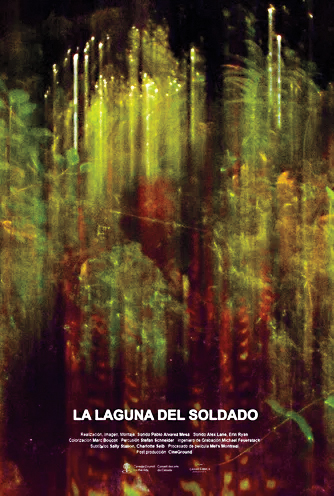

In 1819, at the height of his military campaign against Spanish colonial rule, Simón Bolívar crossed a stretch of high-altitude grassland in Colombia known as the páramo. His troops, utterly unprepared for the frigid temperatures and rough terrain, barely made it through. Most of his men (and their horses) froze to death and were thrown into a lagoon, where they have lain buried ever since. This gorgeous if inhospitable landscape serves as the backdrop for Pablo Álvarez Mesa’s La laguna del soldado, a poetic meditation on how nature subsumes human history.

In lieu of characters and plot, La laguna del soldado presents beautiful images of the páramo along with sporadic voice-over narrations from locals and scientists. Álvarez Mesa creates a contemplative mood that his film’s experimental structure sustains throughout. Almost without us noticing, the environmental and social stories we hear of the Colombian Andes begin to intertwine.

La laguna del soldado

Directed by Pablo Álvarez Mesa

Screenplay by Pablo Álvarez Mesa

Colombia and Canada

2024

Take the frailejón. Long shots focusing on this curious-looking shrub—reminiscent of a giant artichoke or succulent—give way to a scientific explanation of the plant’s significance. The frailejón belongs to the same family as the common sunflower, and it plays an outsize role in the water cycle of the páramo and beyond. It captures water from the moist air, later releasing it into the soil through its roots. The subterranean deposits it creates eventually give rise to rivers. “These creeks connect us with the Orinoco, with the Eastern Plains,” a softspoken voice tells us, referring to one of South America’s longest rivers and the famous plains that surround it. “What we do here is clearly reflected there.”

The social reality of the páramo, however, has never benefited from such cohesion. For hundreds of years, the frailejón has been known by another name to the Muiscas, the Indigenous people of the páramo. To them, the plant holds strong associations with the sun, which its later Spanish appellation failed to grasp. Until 2016, when the FARC guerrilla group signed a peace accord with the government, considerable parts of the páramo had been entirely inaccessible to everyday Colombians—and threats of fresh conflict there remain. This state of affairs recalls Bolívar’s own failed projects of integration. Though his independence campaign through the páramo ultimately succeeded, his dreams of unity for Latin America in a single political community never did.

An interconnected ecosystem belies fragmented societies. Indigenous communities, Spanish colonists, modern armed forces—these men and women span several centuries of clashing human history, and yet they have all intersected with a natural constant in the páramo, one that transcends any particular culture. La laguna del soldado repeatedly builds off details of this kind—the páramo’s bats, its minerals, its fog—to collapse human time and the convulsions of our past.

The exercise feels remarkably appropriate for a country embroiled in decades of conflict and finally fixated on sustaining some kind of peace. Perhaps it should also come as no surprise that a common thread emerges in Bolívar, Colombia’s enduring idol. The start of La laguna del soldado features the film’s only noncontemporary oral narrative. A man with a Spanish accent recites Bolívar’s mysterious poem, “My Delirium on Chimborazo,” which includes reflections about man’s stature in the face of the cosmos.

“Feverish delirium engulfed my mind. I felt as if inflamed by strange, supernatural fire. The God of Colombia had taken possession of me. Suddenly Time stood before me—in the shape of a venerable old man, bearing the weight of all the centuries, frowning, bent, bald, wrinkled, a scythe in his hand,” Bolívar wrote. Even this man who was larger than life, Álvarez Mesa seems to be reminding us, could recognize the primacy of the natural world over and above everything else. The páramo, as a kind of archive, lives on with or without us.