BOGOTÁ — On November 17, speaking before members of the Colombian Air Force, an exultant President Gustavo Petro celebrated the approval of his tax reform just two and a half months after his inauguration. “For the first time in many decades we are talking about taxing the upper echelons of the population in order to finance spending and investments for the poorest people of this country,” he said.

Even as many economists dispute that assertion, the reform’s passage through Congress is Petro’s most important victory in his first 100 days in office.

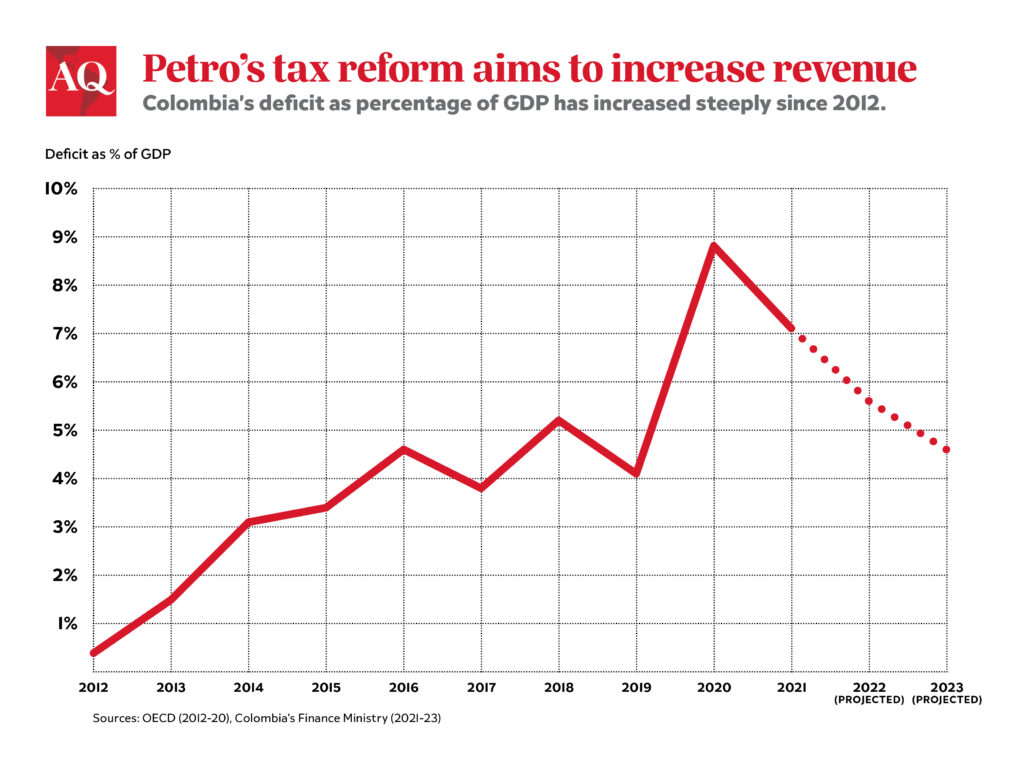

The reform appears fiscally responsible. It raises revenue to reduce the deficit, which rose to almost 8% of GDP in 2020 on the back of pandemic spending. This year, deficit will fall to 5.6% of GDP and should continue to decline. If the fiscal rule mandated by law is respected, the deficit will fall to 4.6% in 2023.

According to the Finance Ministry, the reform will generate new revenue equivalent to 1.3% of GDP in both 2023 and 2024. The largest share will come from extractive industries through a windfall tax on extraordinary profits. The reform also eliminates deductions for royalties paid, which are up to 10% of gross production revenue for coal and 15% for oil.

Other corporations will also pay more. On top of a 35% general tax rate, the financial sector will now pay a 5% surcharge, while hydroelectric plants will pay a 3% surcharge. Other tax deductions will also disappear, so by 2026, non-oil and gas sector businesses will contribute up to a third of additional revenues.

Petro argues that the reform amounts to a more progressive tax framework, but in fact its results will be limited in this regard. OECD statistics show that personal income taxes currently constitute just 1.3% of GDP in Colombia, the lowest level of all member countries. In Mexico, the figure is 3.8%, and in Spain it is 8.7%.

After the reform comes into effect, Colombia’s revenue from individual taxpayers will increase to only 1.5% of GDP, despite a new wealth tax on top earners. Some high-income taxpayers will see a 60% jump in their taxes, but the middle class will not pay more.

The reform will ultimately make Colombia less competitive. The Asociación Nacional de Empresarios (ANDI), the country’s largest private sector industry group, argued that the original bill would have raised taxes on corporate profits from 42% to 67%, the highest rate in the world.

Some of the proposals were watered down, but the prospects for the extractive sector remain worrying. Fedesarrollo, the country’s most prominent think tank, published a study indicating that, for oil companies, the reform would push the effective tax on profits from 36% to 70%.

This threatens investment in a country where the main source of foreign revenue is precisely oil. During the first nine months of 2022, crude sales represented 34% of total exports, worth $15 billion. If capital expenditures fall, oil production levels would decline from the current average of 750,000 barrels per day (bpd). The Colombian Oil Association forecasts a reduction of 160,000 bpd by 2024, which would undermine both foreign revenue and tax revenue. Worse yet, Colombia’s energy self-sufficiency would be threatened if oil production were to fall toward 400,000 bpd, the amount of internal consumption. Some analysts say that Colombia is in the process of killing the goose that lays the golden egg.

There is also the question of how much of the extra revenue will be saved, if any. The answer is not yet clear, since the Petro government faces a long list of unfulfilled campaign promises. In a recent report, Fitch Ratings warned, “Petro’s push for large expenditure increases could lead to large deficits persisting over the medium term if revenues underperform.”

Moreover, the administration inherited a major headache in the high differential between domestic and international gasoline prices. The projected cost of the so-called Price Fuel Stabilization Fund is expected to be 2.5% of GDP in 2022 and 1.6% in 2023. Internal prices are being gradually increased, but under the current plan, equilibrium will not be reached until 2025. In the meantime, Ecopetrol, the national oil company that manages the Fund, will partially finance the Treasury. This will affect its investment plans.

These factors combined will put tremendous strain on Colombia’s economy in the years ahead. Large deficits, inflation and a hostile international environment will be very real risks, especially if Petro remains keen on raising spending and making changes that worry markets.

The tax reform may seem like a triumph. But it could be a typical Pyrrhic victory, in which temporary success comes at great cost. Only time will tell.

—

Ávila is senior analyst at El Tiempo, Colombia’s leading daily newspaper