SANTIAGO — For a casual observer of Chile, the election result might have come as a shock. A country that just a year ago seemed to be undergoing a progressive transformation, with a tattooed, thirty-something president taking office and an expansive new Constitution apparently on the way, now seems to be lurching in the opposite direction. Right-wing candidates dominated Sunday’s election for delegates to write a new charter, taking 62% of votes and likely ensuring that Chile’s market-centric economic model of recent decades will remain more or less intact going forward.

While there were many reasons, including public anger over inflation and repeated missteps by President Gabriel Boric and his leftist allies, one stood out: Fear over violent crime. Chile’s homicide rate has doubled over the past decade, and soared by a third in 2022 alone, shocking a nation that took pride in being one of Latin America’s safest. And here, Chile is not alone: Other previously placid countries in the region, including Ecuador, Uruguay, Argentina, Peru and Costa Rica, have also seen crime rise to the top of the political agenda, or very close. If corruption was the big issue that turned Latin American politics upside down in the 2010s, violent crime may play the same role in the 2020s in many countries. The interesting question is why—and what, if anything, leaders can do about it.

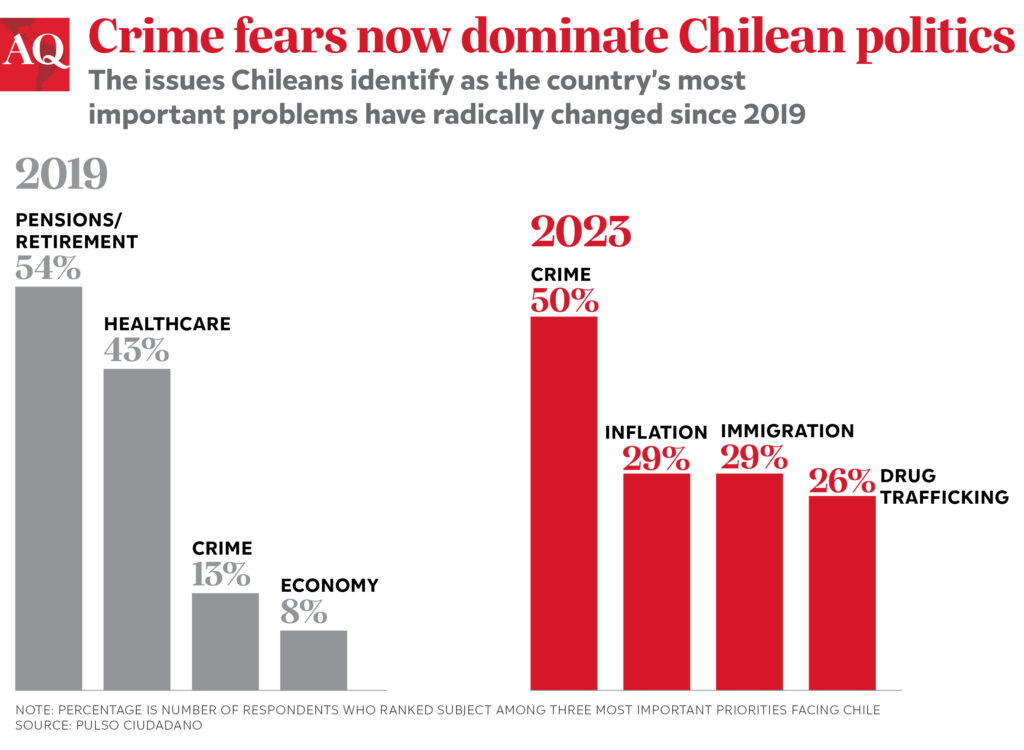

I spent several days in Chile last month, and it should be said: Parts of Santiago still feel quite safe, especially if you’re accustomed to places like Rio de Janeiro or Bogotá. Indeed, Chile’s nationwide homicide rate of about 5 per 100,000 people still compares favorably to Brazil (19), Colombia (26) and even the United States (6). But of course Chileans are not comparing themselves to their neighbors, and there is more to the story than murder alone. In polls, more than one in three Chileans say they or someone in their family has been a victim of a robbery or attempted robbery in the last three months. High-profile crimes including the murder of three police officers in less than a month, the beheading of a homicide victim in April, and rampant cargo thefts of copper, the country’s signature export, have added to the sensation that the rule of law is slipping away. No wonder that 50% of Chileans now rank crime as the country’s most important issue, up from just 13% who said so in the wake of the 2019 protests that seemed to herald a shift left, and health care, pensions and inequality briefly topped the agenda.

What’s driving the crime surge? Security experts and government officials point to a variety of causes including the rising presence of international organized crime groups including Tren de Aragua, a gang with roots in Venezuelan prisons, and changing flows of narcotics that made Chilean ports like San Antonio an ideal shipment point for cocaine from Colombia, Bolivia and Peru to North America and Europe. “These groups are taking advantage of Chile’s greatest asset—our reputation for safety and openness,” one politician told me, noting how Chile’s trade agreements with 65 different countries made it relatively easy for smugglers to hide drugs alongside the country’s famed cherries or wine. Some analysts also blame an “anything goes” atmosphere that prevailed in the wake of the 2019 protests, when anti-police sentiment soared, while others speak of the continued economic and mental health effects of the pandemic.

Fighting crime has rarely been a top priority for the Latin American left, and Boric’s government deserves some credit for pivoting to address an issue that “was not on our radar when we arrived,” as one official frankly told me. The 2023 budget mandates a 4.4% increase in security spending, and Boric has also invested heavily in new police equipment while sending the military to stop more undocumented migrants from crossing the border with Peru. These steps have been too heavy-handed for some in Boric’s base, but as another official put it: “We realize that, if we don’t do this our way, valuing democracy and human rights, the right will be much worse.” Nevertheless, foreign diplomats say Chile still lacks the equipment, intelligence capabilities and legal framework to deal with the evolving organized crime threat. “They’re 20 years behind,” one said. And of course politicians across the spectrum have continued to hammer away at the issue—the party of José Antonio Kast, an ultra-conservative who lost to Boric in the 2021 presidential election runoff, was the big winner in Sunday’s voting.

Lest anyone believe that crime is only a challenge for the left, though, consider what is happening in Ecuador, where an even more alarming surge in murders and gang violence is the biggest reason that right-wing President Guillermo Lasso sits on the verge of impeachment. The conservative president of Uruguay has struggled to tame a homicide rate that jumped by a quarter last year and is now triple that of neighboring Argentina. Indeed, even there, with inflation above 100% and a recession likely underway, crime has rivaled the economy as a concern in some polls as presidential elections approach in October. While reasons vary somewhat by country, the insatiable appetite for drugs in both traditional consumer markets like Europe and the U.S., and increasingly within the region itself, is an obvious common thread. “Latin America is producing more cocaine than ever before, and this has a knock-on effect not just through the Andes, but throughout Latin America,” crime expert Jeremy McDermott said on a recent episode of the Americas Quarterly Podcast.

In the mid-2010s, a series of scandals including Lava Jato shook up politics throughout the region. Corruption suddenly became the number-one priority in polls in several countries, and anger over the issue swept out one surprised government after another. Today, violent crime appears to be occupying that same role: A real problem, without a doubt, but one that is also easily magnified by social media and at risk of being exploited by authoritarian leaders promising miracle solutions. It is no accident that El Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele’s draconian security crackdown, which has put 2% of his country’s adult population in jail, in many cases without due process, is gaining so many admirers throughout today’s Latin America. While in Chile, I heard Bukele’s name invoked almost as much as Boric’s, both as a role model and a nightmare scenario. A shock poll last month showed 53% of Chileans were in favor of suspending constitutional liberties in Greater Santiago, and putting the military on the street, in order to subdue crime. Unless Boric and all of the country’s democratically minded politicians can work together to get their arms around the problem, Chile’s future could come to resemble its past in ways that are much more destructive.