“This young man, he’s competing in a real war here in São Paulo,” said Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, as he grabbed the arm of a sheepish, grinning Guilherme Boulos, at a May Day event in São Paulo, and held it aloft. “Nobody can defeat this kid.”

It was a moment rich in symbolism, for both short- and long-term reasons.

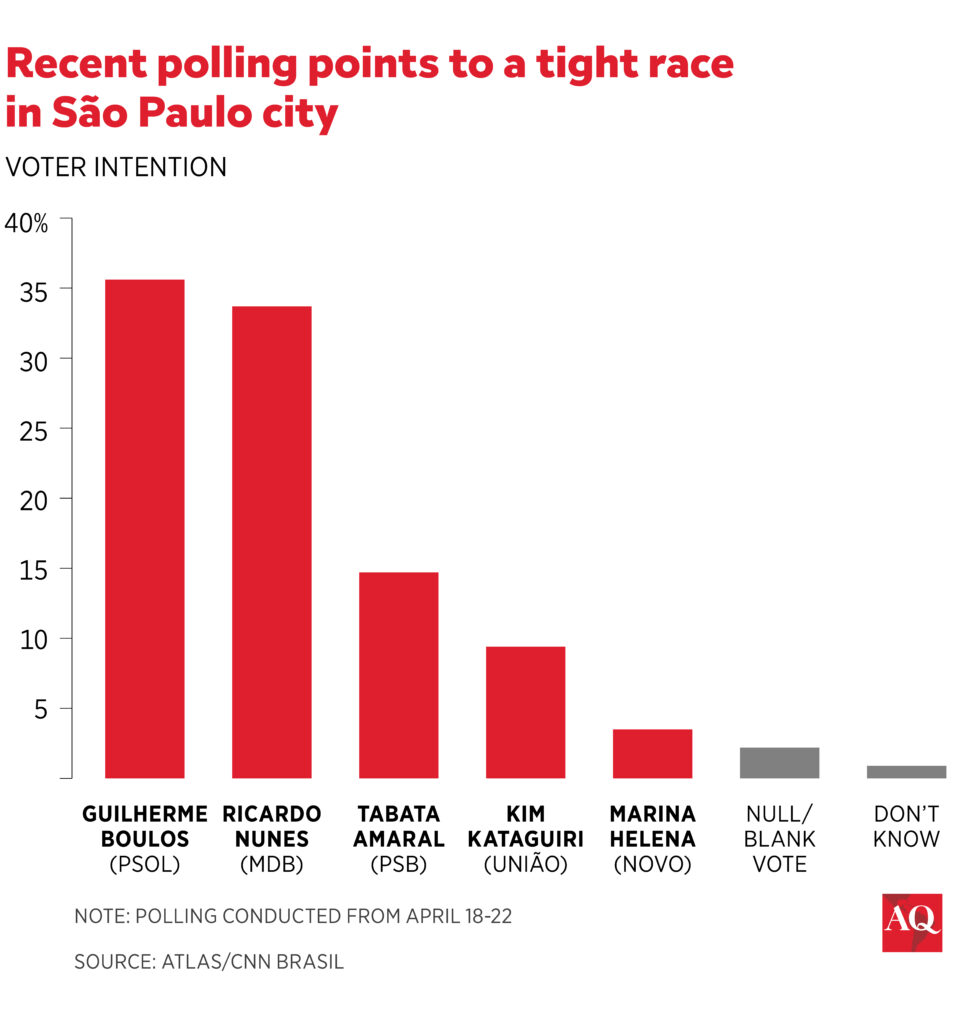

In October, Boulos hopes to be elected mayor of Brazil’s biggest city, in what looks like a tight race against the incumbent Ricardo Nunes, who is backed by another former president, Jair Bolsonaro on the right.

If Boulos wins that race, he will be well-positioned to claim an even bigger prize. At age 41, and with a thick black beard, Boulos bears more than a passing resemblance to a young Lula—and has long been seen as a possible heir apparent at the national level. But first, he will probably need to complete a transition from polarizing left-wing organizer to mainstream politician, just as Lula himself did in the early 2000s.

A new face for a new Brazilian left?

Unlike Lula, who rose from poverty as a labor union leader, Guilherme Boulos is the son of two doctors from São Paulo. Marcos Boulos, Guilherme’s father and a well-known infectious disease specialist at the University of São Paulo, told AQ that the younger Boulos’s social conscience first emerged while driving around the country with his young son to see soccer matches featuring the Corinthians team (also Lula’s team of choice). On these journeys, father and son would sometimes pass people begging on the side of the road.

“He was uncomfortable seeing that,” said Marcos Boulos. “He’s had a clear social vision since he was a child.”

At 19, Boulos left his parents’ household to live among the homeless. He soon became the leader of the Homeless Workers’ Movement (MTST, for its initials in Portuguese), an organization that conducts large-scale wildcat occupations of land. Using tactics similar to the better-known Landless Movement (MST), but working in urban areas, the MTST targets unused land owned by the public and private sector, and pressures for it to be expropriated by the state and given over to homeless populations. The group has conducted many dozens of occupations, sometimes with hundreds or thousands of people, and now claims to have a presence in 14 states.

Boulos made his name leading an occupation of a large plot owned by Volkswagen (which was intending to sell it) in 2003, during the first Lula administration—a time when much of the left was treading cautiously, hoping not to undermine a government seen as friendly. In a separate occupation in 2017, Boulos himself was briefly arrested.

Boulos and the MTST have long drawn criticism from the right and others who the organization as a danger to private property rights. Boulos’s rival in the mayoral campaign, Ricardo Nunes, has called him an “invader of land, who disrespects the law and doesn’t maintain order.”

During his activist years, Boulos gained a reputation for being a talented negotiator, often able to defuse tensions with local police forces and other parties. He gave Lula a show of support when the latter’s political fortunes were at their lowest point—rallying the MTST to a vigil at Lula’s political headquarters outside São Paulo just before his arrest in 2018.

That same year, Boulos decided to enter party politics. He was a long-shot candidate for president for the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL) that year, earning less than 1% of the vote. In 2020 he made a first run at the São Paulo mayorship, losing by twenty points to incumbent Bruno Covas.

In 2022, he ran for federal deputy, and won with the largest total of votes in the state of São Paulo, topping Eduardo Bolsonaro, the former president’s famous son. Nationwide, his vote total was second only to right-wing firebrand Nikolas Ferreira.

A different São Paulo mayor’s race

This time, in the São Paulo mayoral race, Boulos is putting forward some more moderate proposals. He’s suggesting boosting the size of the local police force and using technology to trace stolen phones, amid a rise in cell phone theft and concern about crime. He’s also made outreach to evangelical pastors in the run-up to the official start of the race, looking to make inroads among an important bloc of voters where the right has found deep purchase.

On a recent interview on a morning radio show, he sought to dispel the idea that he’d run a fiscally irresponsible mayorship. “Rest assured,” said Boulos. “This fiscal hole that [Ricardo Nunes] produced, with lack of planning and electoral spending, in my mayorship that won’t happen.”

On the left, Lula hasn’t forgotten the support Boulos showed him when many counted him out—and now, he’s lending Boulos vital help in his second run for São Paulo mayor, showcasing the national importance of the race.

For the first time, Lula’s Workers’ Party isn’t running a candidate, allowing Boulos to draw unified left-wing support. And Lula himself persuaded still-popular former São Paulo mayor Marta Suplicy to join Boulos’s ticket as vice-mayor, hoping to lend an air of moderation and competency to a candidate many still see as a young idealist.

Ricardo Nunes, the current mayor, may be a more vulnerable target than Covas, who died in office in 2021, causing Nunes to assume the mayorship—he’s more directly associated with Bolsonaro, who lost in São Paulo in 2022. But incumbents usually have the advantage in São Paulo mayoral races.

Though highly unequal, the São Paulo of Boulos’s day is richer than it was in Lula’s youth, presenting a new challenge to the construction of a left-wing electoral coalition. This election may turn on the poor but not destitute neighborhoods of the city that were once strongholds of the left, but went for Bolsonaro in 2018 before flipping back in 2022.

What’s clear is that this race, and what it portends for Boulos, has major implications for national politics.

“Whether you like Boulos or not, if he wins, it’ll be very important for the future of the Brazilian left,” said Camila Rocha de Oliveira, a political scientist at the University of São Paulo. “The (Workers’ Party) is hegemonic on the left, and there’s a difficulty in renewing [the ranks of politicians] that’s very serious.”