On September 4, Chileans will vote on whether to approve or reject a proposal for a new constitution. A year ago, a path to approving the new constitution seemed clear—but now, the outcome of the vote is very much in doubt.

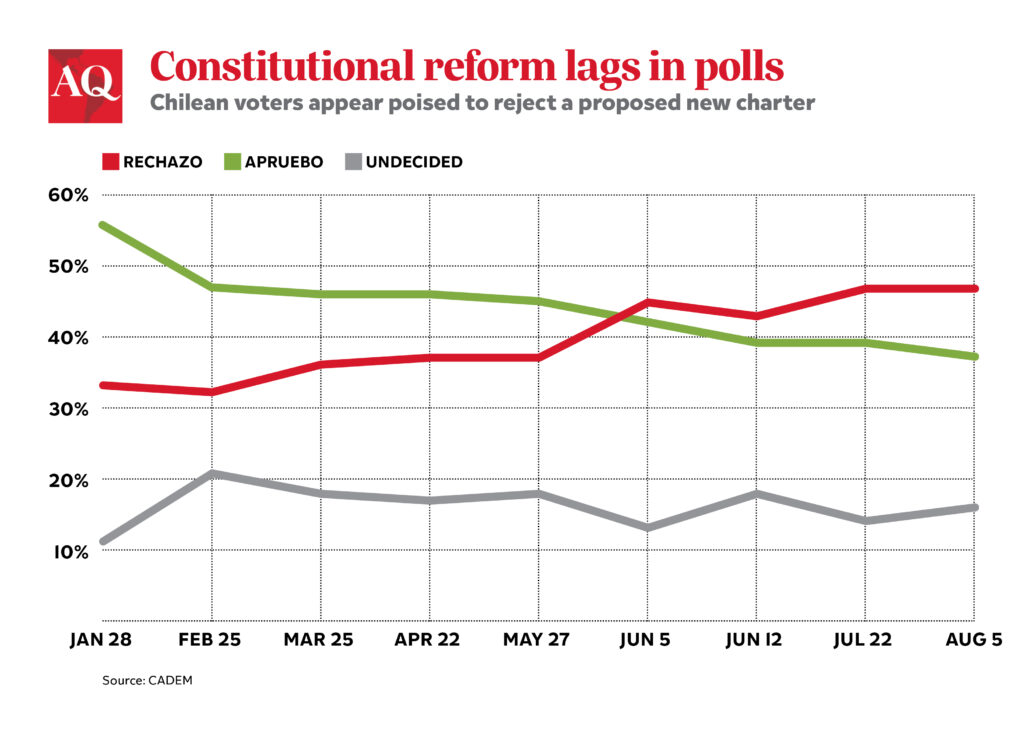

Polls have consistently shown voters are likely to reject the new constitution. But the referendum will be the first held in Chile with mandatory voting in the last ten years, leaving a question mark over how much this will influence participation—and how the possible inclusion of new voters could affect the outcome. In a context where everything seems fragile, even political preferences themselves, the result is hard to predict.

A new constitution was the solution proposed by Chile’s political elite in the wake of the protests of 2019, amid the worst crisis since the return to democracy. Even though the country’s political institutions were at a low point, they showed the strength to strike an agreement and define an exit to the crisis. In a subsequent vote, 78% of voters supported writing a new constitution, and 79% said an elected constitutional convention should write it.

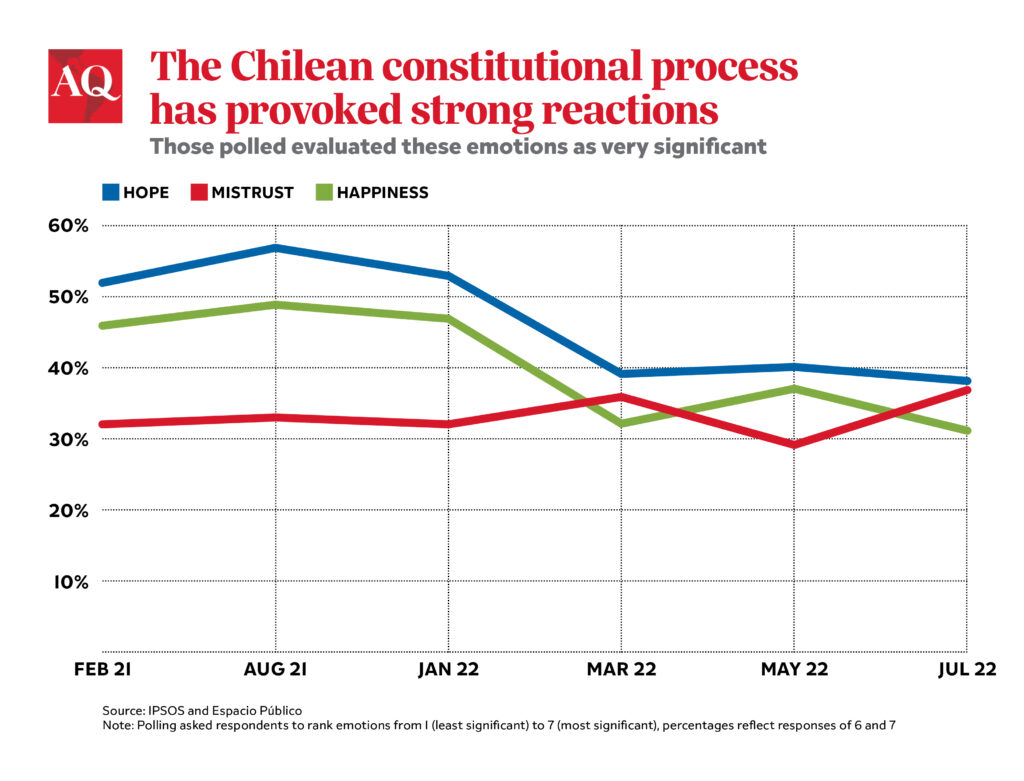

The work of the Constitutional Convention started on July 4, 2021, with high expectations. A study conducted by Espacio Público shows how public opinion has changed within the last year.

Hope and happiness prevailed during the first half of the Convention’s work. But as discussion of the final document began and scandals hit the Convention, that shifted. By the end of July, the sense of hope had been joined by uncertainty and mistrust.

That uncertainty has multiple causes, including some factors outside the constitutional debate. Chile is facing exceptionally high inflation, driven by both international and local forces, which has made life difficult for vulnerable Chileans already reeling from the pandemic. Security concerns have also risen, as homicides rose by nearly 30% during the first half of 2022.

It’s a paradox that this opportunity for major regulatory and institutional change has emerged just as the sense of material and physical insecurity is growing—a trend whose immediate precedent is not only the pandemic but the 2019 protests themselves.

A more moderate electorate

Most Chileans don’t precisely support either of the options, Approve or Reject, that will be on the ballot—as the latest survey conducted by Espacio Público and IPSOS showed. Groups that want the new draft to be put into place without any changes aren’t numerous, and neither are those that want to keep the current charter, which dates from 1980, without modifications.

The majority is split between those who support approving the new constitution and making changes in the short term, and those who support rejecting the new constitution and agreeing instead on modifications to the current charter. That fact contradicts the notion that the discussion in Chile is polarized between the extremes and suggests that the side that wants to win should propose the changes they want to make in advance.

Both sides have now sought to do so. Several weeks ago, the right-wing parties (UDI, RN and Evopoli) presented a document reiterating their position on rejecting the new draft but affirming that Chile does need a new constitutional text. Although the document presents more general points, it does establish some relevant commitments, including committing to a social rule of law that guarantees social rights, which was discussed in 2005 during the constitutional reform led by Ricardo Lagos but opposed by the right. But the parties have not clarified how discussion on a new constitution would be conducted if this draft is rejected.

For the forces supporting the Approve side, reaching an agreement took longer. President Boric had to publicly urge the parties in his coalition to do so. It wasn’t until August 11, less than a month before the vote, that an agreement was signed outlining changes to the constitution if it is approved.

The agreement faces up to the doubts generated by the new constitution, putting the most important changes it proposes at the forefront of the conversation—issues like the idea of a social state, recognition of Indigenous collective rights, environmental protection and the emphasis on gender felt throughout the text.

During the campaign, those issues have concerned the electorate and widely divergent interpretations on controversial topics have made things difficult for the Approve campaign.

Indigenous issues have proved especially complex, including provisions on plurinationalism, Indigenous justice and public security. Part of the problem is that the constitution draft leaves it unclear what the exact implications of its provisions on these topics are. That has been left to Congress to decide—but the agreement helps make clearer what those decisions will look like, since the agreement signals how the governing parties will later vote.

But perhaps the most important question raised by the Approve campaign’s agreement is whether it arrived in time to make a difference in the result.

The other major challenge for the referendum is that the Approve campaign’s fortunes are tied to the evaluation of President Boric’s government, an area in which there is room for improvement. Paradoxically, this progressive government’s main challenge is to offer certainty. The challenge is to set out a political itinerary that addresses unresolved popular demands that have been completely neglected by the political class. Short-term and medium-term tasks must be managed simultaneously: Physical and economic insecurity must be confronted energetically, but at the same time the government must pursue agreements responding to complex, outstanding problems such as pensions and healthcare.

Little is clear about what will happen after September 4, but a victory for the Reject campaign would represent a brutal setback for the government—and discussion would continue about how best to get a new constitution. If Approve wins, the main challenge will be to ensure that the process of implementing the new text includes all the main political forces in the country, and making sure the technical and political aspects complement each other.

—

Mundaca is executive director of Espacio Público, a Chilean think tank. She formerly worked in Chile’s Department of Immigration during the second administration of Michelle Bachelet.