SANTIAGO — Almost 35 years ago, just as Chile was emerging from its long dictatorship, my Canadian politics professor Stephen Clarkson, together with Christina McCall, published the first volume of their magnificent biography of former Canadian Prime Minister (and father of the current one) Pierre Elliot Trudeau. The book began with the words: “He haunts us still.”

Trudeau was a dashing, witty progressive who dated Barbra Streisand and debated with Fidel Castro. His social liberalism, commitment to multiculturalism and insistence on pushing through a new constitution created, in many ways, today’s Canada. Augusto Pinochet, on the other hand, was a terse, murderous international pariah who helped destroy Chile’s democratic tradition. His adoption of neoliberalism, erasure of Chile’s developmentalist past, and insistence on pushing through a new constitution created, in many ways, today’s Chile. Larger-than-life leaders tend to create divisive, complicated legacies which go on to haunt us for generations. And so, Pinochet haunts us still.

Now, on the 50th anniversary of the coup d’état that brought General Pinochet to power, debates in Chile show just how complicated that relationship is. Chile is, clearly, a very different country than it was not only 50 years ago, but 20 years ago, when President Ricardo Lagos commemorated the coup’s 30th anniversary with solemn symbolism. Today the country is richer and better educated. It is far more liberal and open, having overcome many taboos. But it is also a country that has come through a violent uprising, a pandemic, and a failed constitutional process. The country seems to be witnessing the collapse of its party system, a questioning of its economic system, and, if polls are to be believed, a wavering commitment to democracy.

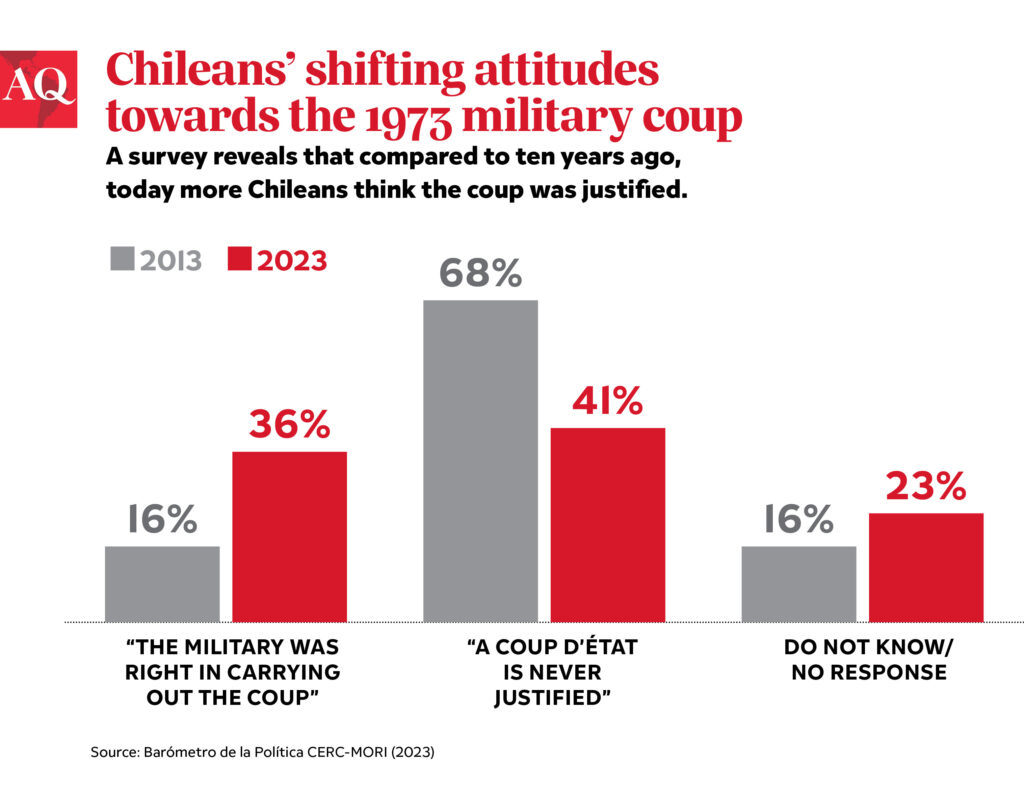

Over the last 18 years or so, the number of Chileans who believed that Pinochet had saved Chile from Marxism, according to CERC-MORI, ranged between 19 and 24%. This year that figure jumped to 36%. Similarly, in the same period, 2005-2013, an average of 24% thought that the military was right in carrying out the coup. In 2023, that number rises to 36%. For the last two decades, CERC-MORI has also asked whether coup d’états are ever justified. In 2003 48% agreed with the statement that they are never justified, rising to 65% in 2006, and 68% ten years ago, forty years after the coup. Today, that number has fallen to 41%.

In addition to these opinions, there is the electoral evidence. After rejecting last year’s constitutional proposal, presumably for some of its more progressive content, Chileans went on to elect a new Constitutional Council controlled by Republicanos, a far-right party founded in 2019. Their proposals for the new constitution include a total abortion ban and immediate expulsion of illegal immigrants. The leader of Republicanos, José Antonio Kast, is a brother of a former minister in Pinochet’s government. With international models such as Santiago Abascal in Spain, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Javier Milei in Argentina, Kast has been an outspoken defender of General Pinochet’s legacy. He claimed in late 2021 that Chile under Pinochet was different from what “happened in Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua. I think that Nicaragua fully reflects what did not happen in Chile (with Pinochet): Democratic elections were held and political opponents were not locked up. That makes the fundamental difference.” Today, Kast is in pole position for the 2025 presidential elections.

As the 50th anniversary of the coup d’état nears, are Chileans feeling less democratic? Not necessarily.

According to the latest CEP poll, crime (54%), drugs (23%), corruption (21%) and immigration (15%) are among the country’s top concerns. Chileans may not necessarily be hoping for a dictatorship as much as they want safety and security. As in much of Latin America – like indeed, elsewhere – those qualities are all too often associated with authoritarianism. In this sense, one must be careful not to conflate the rise of the far right with atavistic sentiments about the dictatorships of the past. Kast may invoke the ghost of Pinochet, but his discourse, centered on crime, corruption and immigration (with a healthy sprinkling of anti-wokeness) addresses problems that are rooted very much in the 21st century.

The far left, which likes to invoke its own ghosts, doesn’t understand this. It continues to fight the fight of the past, insisting, as the economist Manuel Riesco did recently, that Allende’s presidency was a great success. “The Chilean Revolution”, he wrote in El Mercurio, “honored the classical description of these remarkable periods, overcoming unimaginable difficulties; it accomplished in hours what in normal times is not achieved in months, in days what is not achieved in years, and in years what is not achieved in centuries.”

Other protagonists of the time are less hyperbolic in their evaluation. Oscar Guillermo Garretón, a founder of the once-revolutionary MAPU (Movimiento de Acción Popular Unitario), judges that the mistakes of the Unidad Popular “are an inescapable part of its defeat.” Luis Maira, Sergio Bitar and Ricardo Lagos, among others, would probably agree. They were there.

But over the years Allende became less of a flawed democrat and more of a martyred revolutionary (both things can be true), and a generation emerged that only knew Allende as a pair of iconic glasses, Allende as T-shirt. President Boric came to political maturity in that milieu, but in power, has come to appreciate many of the lessons that the older generation learned the hard way. As Garretón has written, that “democracy and human rights are not relative”, “the deeper the changes, the more profound, the broader social and political forces committed that are needed”, a “categorical rejection of violence and armed struggle” and that “there is no viable economy in the twenty-first century without a combination of market and regulations that correct its imperfections”.

On the 50th anniversary of the coup Chile has waded once again into the same old debate on the causes of the coup, whether Allende was a success or failure, the role of the United States, and how much of today’s Chile is the result of Pinochet’s legacy. But unlike previous major anniversaries, the country is also debating a new constitution, in a process that was specifically intended to institutionally erase the most lasting remnants of Pinochet’s legacy. And yet, looking around the current political landscape, it appears that Chile, after everything it has been though in recent years, may end up with a conservative constitution and an extremist president. Clearly, he haunts us still.

__

Funk is assistant professor of political science at the University of Chile’s Faculty of Government and a partner in Andes Risk Group, a consulting firm.