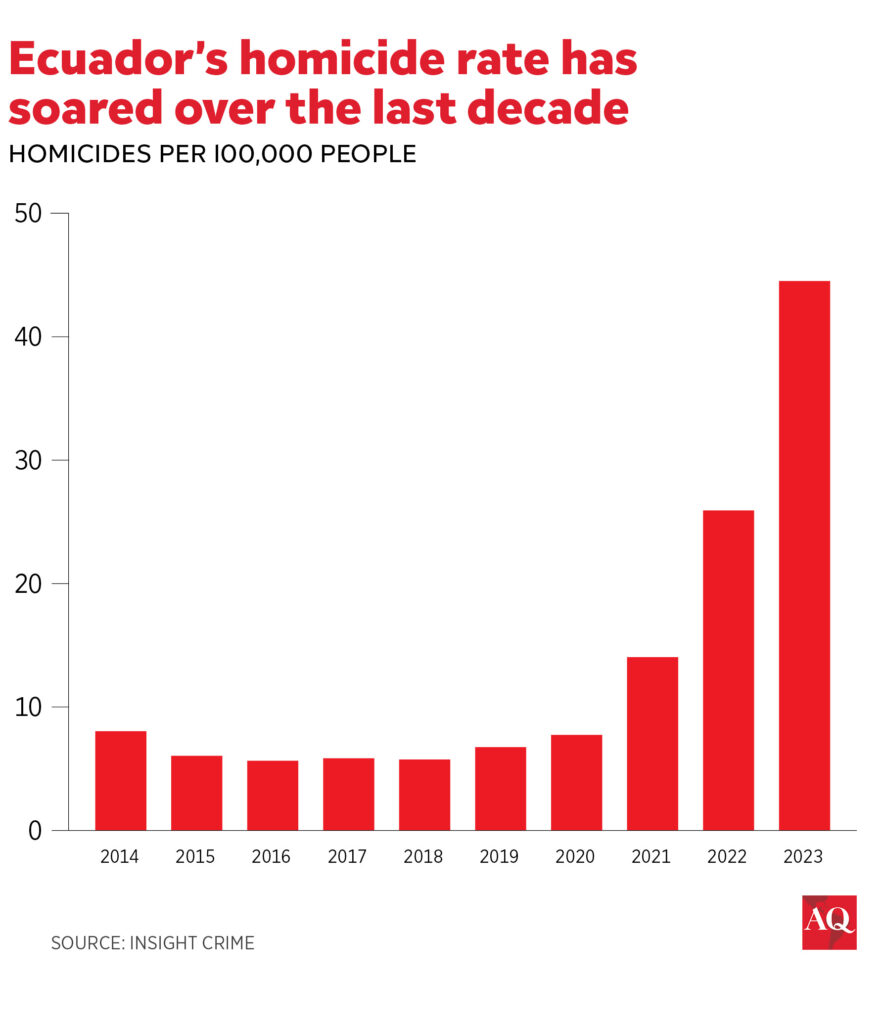

QUITO — Two months have passed since Ecuador’s President Daniel Noboa declared a “state of internal conflict” and deployed more than 30,000 security forces to deal with scenes of drug-related violence that shocked the country and, indeed, the world.

The emerging picture is of a very popular president, boasting an 80% approval rating as Ecuadorians rally behind his crackdown; an apparent decline in homicides, but persistent levels of other criminality, including kidnappings and extortion; and a great deal of information we simply don’t know, as the government seeks to control the narrative and hold the country together.

Noboa, just 36, had an unprecedented start to an unusually shortened term. Mostly reserved and soft-spoken, he has granted only a few interviews to local and international news outlets, maintaining nevertheless an upbeat tone about the outcome of the fight against organized crime. “We have notably improved on issues like security, reducing dramatically the number of daily violent deaths that were the byproduct of a state overtaken by narcoterrorism,” he said in an interview with CNN en Español earlier this month. Most observers believe he is clearly paving the way to run again for the presidency at the next election in February 2025.

Noboa has ordered the armed forces and the National Police to the streets to contain the operations of as many as 22 organized criminal groups—including the infamous gang known as Los Choneros—operating nowadays in the Andean nation in connection with bigger, meaner international cartels. The strategy has been compared by some analysts to what President Nayib Bukele has implemented in El Salvador, although Noboa says he will respect Ecuador’s Constitution.

Actual data about his government’s performance has often been hard to get, or seemingly leaked to the media in an incomplete fashion.

The government has not officially released homicide data since the crackdown began. Newspaper El País reported earlier this week that the number of homicides per day has declined dramatically from 40 to 12, but did not reveal a source or say when the comparative data was from.

Since Noboa implemented the state of emergency on January 9, 14,765 people have been arrested, 280 of them on terrorism charges, according to the Ecuadorian military. It is not clear, however, how many of those arrested have been charged or released.

Meanwhile, despite the increased security presence, between January and early March, 1,543 cases of extortion and kidnappings occurred, news agency EFE reported last week, citing National Police data. However, EFE did not provide comparative national data, only saying that the increase of such cases in Guayaquil, the nation’s most populated city, represented a fivefold increase compared to the same period in 2023.

Indeed, one of the few clear takeaways is that Guayaquil remains ground zero in the fight. Its port is the country’s most important, and has become a target for these groups working for the Sinaloa and Jalisco Nueva Generación cartels, as well as for the Albanian mafia, known as Los Albaneses. As recently as 2019, military intelligence detected 10 groups operating in Guayaquil, but now, according to government data, a total of 20 organized crime entities are fighting for supremacy in the city. They are now considered not just cartels or criminal gangs, but terrorists.

Ecuador’s Constitutional Court recently ruled that the state of emergency was constitutional, and President Noboa extended it until April 8. Local analysts consider that additional extensions can be expected in the foreseeable future as the state drags on a confrontation with no clear endpoint.

A popular president

Despite the murky early data, Ecuadorians seem to have found some relief after recent events and atrocities that claimed, among others, the life of the presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio last August.

Regular citizens perceive Noboa as “a president who is making decisions” under challenging circumstances, Quito-based analyst Max Donoso-Muller told AQ. That iron fist or mano dura stance on security is greatly helping him with his popularity while boosting his political capital. “I believe his success is in having formed a strong political team that has made the legislative majority work,” he added.

With that popular support, Noboa has managed to score some political victories as well. His administration maneuvered to hike the value-added tax (VAT) from 12% to 13%. The law passed on February 9 allows for a tax that can be increased up to 15%, at the president’s discretion. Such an increase is scheduled to happen in April.

In parallel, the government is negotiating a $3 billion extended facility agreement with the International Monetary Fund, which Noboa expects could be sealed in the next three months. The talks are not easy, as Ecuador must pay $1.1 billion to the multilateral lender in 2025 to amortize previous loans. It is possible that the IMF would ultimately request an increase in the VAT to 15% and a drastic reduction in subsidies for fuels, which last year alone cost $2.3 billion, according to estimates by the nation’s central bank.

First test

With several pieces in motion, Noboa’s administration will face another test on April 21, when Ecuadorians will vote in a referendum on keeping the armed forces patrolling the streets, stricter gun control, and increased prison sentences for organized crime offenses, among other measures.

Noboa is trying to use the referendum “to his advantage, to strengthen his career for the 2025 elections,” said Esteban Ron, dean of the law school at SEK University in Quito. Undoubtedly, “if he did not have high popularity, he would not have made this consultation,” he added.

The referendum can easily become a plebiscite on Noboa’s administration, in which legislative changes take a back seat and become a tool with which citizens punish their leaders. Shortly after the referendum, the presidential campaign season kicks into motion, as by early August, presidential candidacies must be registered for the February 2025 election. It remains to be seen how this war will play out for Ecuador and its citizens.

__

Imbaquingo is a political journalist working for Quito-based El Comercio. He has covered Ecuador’s politics and economy for more than 26 years. He was a 2012 Knight Fellow at Stanford University.