This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on closing the gender gap | Ler em português | Leer en español

GUAXUPÉ, Brazil — She always dreamed big, maybe too big for this coffee and cattle town in the mountains of southeastern Brazil. So when she turned 18 and word came that a family friend in São Paulo needed a nanny, she jumped at the chance — and took the overnight bus south.

The years that followed were challenging, and for a while those dreams seemed to recede. She discovered a gift for taking care of children; but, cruelly, could not bear any of her own, miscarrying a dozen times before finally giving up. The monstrous city gave her opportunities, but some troubled times as well. When she got back on her feet and saved up a bit of cash, she opened a modest shop in her house, in what was meant to be the baby’s room, selling elaborate, bejeweled skirts she designed and stitched herself.

The house suffered from water outages and chronic mold, and the fabric would often rot before she could finish her work. Her husband, a part-time metalworker and something of a recluse, complained constantly about the people coming in and out. And so the shop soon closed, another link in a growing chain of unrealized ambitions. But it was never in her nature to be bitter; it was a shrug, a rueful laugh, and on to the next thing. “Fazer o quê, né?” What are you gonna do? Back to working as a nanny or maid, she decided — at least for a while.

And that was how Silvia first came into our lives, around the time of her 42nd birthday, in early 2014. Working for an American-Brazilian family like ours, with two young kids who enjoyed exotic meals like sesame chicken and Frito pie and shouted across the apartment at each other in a mix of English and Portuguese, could be unsettling. But Silvia fit in right away and — in an auspicious sign of things to come — she immediately taught herself enough English to navigate the cookbook we kept on the shelf, making careful notes in pencil next to the recipes and doing the imperial-to-metric conversions herself. Five days a week, our house echoed with Silvia’s sing-song voice, pealing laugh and the daily hiss of the pressure cooker, producing another batch of her delicious feijão.

One day, Silvia mentioned she had learned how to bake cakes while working briefly for a caterer, and had even sold a few to friends. Erica, my wife, asked if she might make one for our son’s birthday.

Of course, Silvia said.

Well, could it be a Batman cake?

Show me some pictures of what you want, Silvia replied, and I’ll do my best.

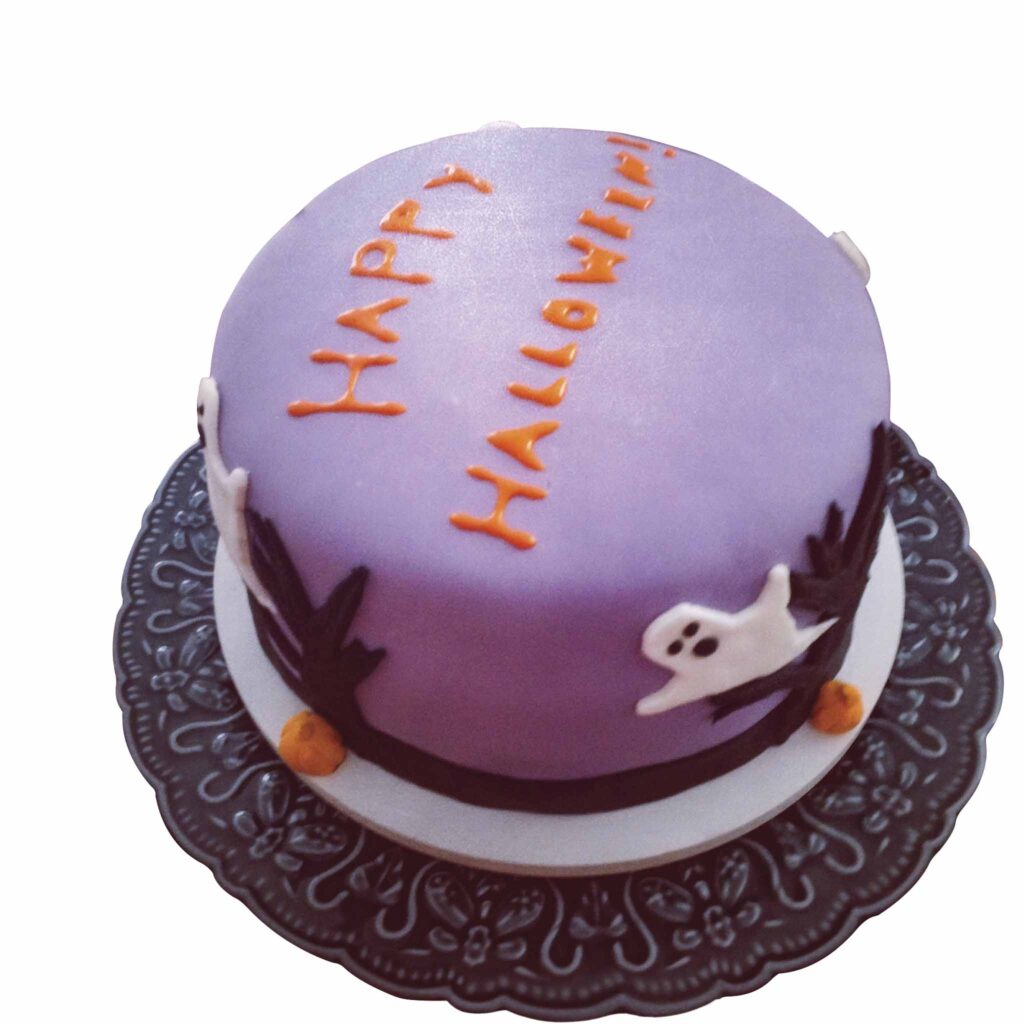

The final result was so sublime, so utterly perfect, that I heard Erica shout in delight — “Oh my god!” — from across the apartment. The cake featured a Batman logo and a dark, sinister skyline and, once we finally brought ourselves to cut it, we discovered it was delicious as well. It confirmed what we had already begun to suspect: We were in the presence of a true genius, someone blessed with God-given artistic talent and incredible craftsmanship.

A series of small miracles soon unfolded. In rapid succession, there was a cake with a blond girl sitting on her bed, green shamrock cookies with an edible elf, and — finally — an elaborate production with a train tunnel and airplanes that could only be described as our seven-year-old son’s wildest dream come to life.

People at our parties were rightly stunned, and word spread quickly. Silvia became an overnight sensation, selling cakes to the small anglophone expat community of São Paulo, with more business than she could possibly handle.

These were the best of times, for all of us. We spent long hours in the kitchen, swapping recipes and telling stories while watching Silvia obsessively labor over her creations and grow ever more ambitious in their scale and detail. She and Erica grew particularly close. Outside work, Silvia sometimes came with us to weekend piano recitals and soccer games and treated our children as if they were fully her own. But after only a year and a half together, in mid-2015 I received an offer for a fantastic job in New York. Our kids were reaching an age where we wanted them closer to family. It was time for the Winters to leave Brazil.

Breaking the news to Silvia was the hardest, and ended with all of us upset. Soon afterward, she took me aside and quietly asked, Can I come with you? I tried to explain that we could never afford help in the United States like we had in Brazil, that the economics were so dramatically different; that a visa would be impossible to get. It was the truth, but it sounded like a lie. She nodded with sad acceptance — Fazer o quê, né? — and began searching for a new job.

One afternoon, as we were packing our things, I asked Silvia if she had thought about making cakes full time, or even opening a shop. She smiled and said her sister and several friends had encouraged her to do so. But she couldn’t work out of her own home — that had failed once before — and she didn’t have money to do anything else. When I asked if she might consider applying for a loan at a bank, she threw her head back and laughed, like it was the funniest thing she’d ever heard.

“Ah, Senhor Brian, they’d never give money to somebody like me.”

And so Silvia found another job as a maid, with an expat family of friends around the corner. Even before we left, she seemed diminished somehow, like a light in her was going out. Her posts on Facebook tried to maintain a happy face: “Sad today, but we have to move forward! God in control alwaysssssssss!!!” On my return visits to Brazil for work, I often went to see her. She looked thin, gaunt. Once, I asked if she was still baking cakes. “Who has the time for that?” she shrugged. “Maybe one day.”

“She discovered this gift”

Years later, it remains incredibly difficult, perhaps impossible, for me to describe our relationship with Silvia. Certainly, there’s nothing in the modern U.S. experience that quite captures it. She was our employee, it’s true. She was also our friend — and somehow more than that, too. I have wondered if, in the long Brazilian tradition of domésticas and babás, maids and nannies, people come into your house and you spend long days together and share your lives and sometimes they become as much a part of your family as an aunt, cousin or sister. I know there are issues of class and power — “Senhor Brian” — and race and history wrapped up in all of this. Or … maybe it was actually none of these things. Maybe Silvia was just one of those magical souls who come into your life, and it was as simple as that. What I can say, without hesitation, is that the bond the five of us forged was greater than any label, or even our limited time in Brazil. We knew we had a relationship that would last forever.

So you can imagine our grief when, in 2017, we received word that Silvia had suddenly passed away. There were no details, only some cryptic posts from her friends and family on Facebook. Erica exchanged a few texts with her sister, Luciana, but didn’t learn much. We needed to know more.

Several months later, I made the five-hour drive from São Paulo to Guaxupé, Minas Gerais, and met her sister and mother at a churrascaria for lunch. The mood was bright and jovial; we were all happy to be talking again about Silvia. Over picanha and pasta, they laughed and told me how Silvia would take the overnight bus home just to attend family parties, dance until 2 a.m. and then go straight to the bus terminal and head back to São Paulo. I showed them some pictures of us together, and of her cakes. They oohed and aahed in delight.

“She discovered this talent, this gift, she didn’t know she had,” Luciana said. “She wanted to do something with it, maybe come back here. It would have been great, you know? But she couldn’t figure out how. … And then she ran out of time.”

Inevitably, the conversation turned to the end. They didn’t know much either. They said Silvia had gone into an urgent care facility on a Thursday morning, and died around 3 a.m. the next day. The cause, according to the death certificate: colon cancer. She was 45. “If she knew she was sick, she didn’t tell any of us,” Luciana said. “We had no idea.”

As we left the restaurant and lingered on the sidewalk outside, her mother, who had been so quiet, so stoic the whole time, took my hand in hers and gave it a reassuring pat. “Ela amava vocês,” she said with a big smile. “She loved you guys.” We loved her too, of course. But to this day, I still can’t shake the feeling that we failed Silvia; that we could have — should have — done more to try to help her. I play out countless alternate timelines in my mind in which we try to move heaven and earth to get her a U.S. visa; in which we rally our friends to put together a small loan with some starter capital for a shop. But that’s all gone now. The only thing left, I suppose, is to try to help create a world where factors like gender, race and class no longer prevent such magnificent talent from being fully realized. Where “somebody like me” is not a liability, but an asset.