When I was in Bogotá in early 2023, I spoke to a young senator called Miguel Uribe Turbay. I hadn’t met him before, and I came away impressed by a politician whose life had been marked when he was just four by the murder of his mother, Diana Turbay, following her kidnap by Pablo Escobar’s henchmen. An articulate conservative, but not extreme, I thought Miguel Uribe had a future.

But that future was brutally snuffed out when he was gunned down in April as he began his presidential campaign. Instantly, my mind, like that of many Colombians, went back to 1989, when three presidential candidates and several senior officials were murdered on their campaign trails on the orders of Escobar or his peers.

Then, when narco-guerrillas of the Estado Mayor Central exploded a truck bomb outside an airbase and brought down a Blackhawk helicopter with a drone in August, killing a total of 19 people, it recalled the period at the turn of this century when FARC guerrillas staged large-scale attacks on towns and military garrisons, threatening to turn Colombia into a failed state.

Fortunately, Colombia is not as bad as it was then, nor as it was in 1989. But the latest events are a warning that it is going backwards fast. Security is deteriorating in large parts of the country, illegal armed groups are growing, and security forces are weaker than they were a decade ago. What makes this even more galling is that, not so long ago, things seemed to be going well.

A squandered opportunity

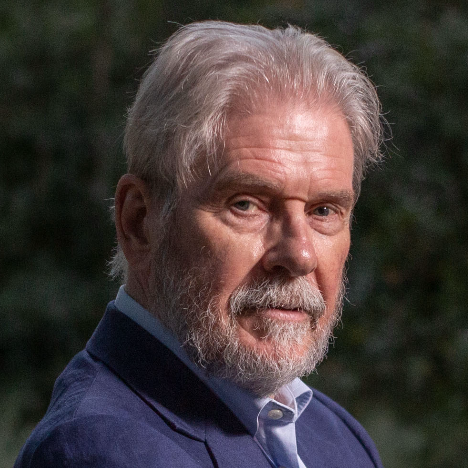

During Álvaro Uribe’s (no relation to Miguel) presidency from 2002 to 2010, Colombia built up its security forces. Uribe turned a conscript army into a semi-professional one. He expanded a large helicopter fleet, essential for military operations in a country of impossible geography. He stationed police in all 1,100 municipalities. By strengthening the state, he persuaded some 30,000 right-wing paramilitaries to disarm (some of whom ended up in jail). He slashed coca cultivation and thus the income of many armed outlaws. During that period, the murder rate fell from 69 per 100,000 people in 2002 to 26 by 2016.

There were blemishes, especially the “false positives”: Over 6,400 civilians, mostly young, were murdered by the army and passed off as guerillas. Álvaro Uribe was later accused by the left of having ties to paramilitary groups, and in July was convicted of witness tampering in a related investigation. (He is appealing the conviction and denies wrongdoing.)

Even so, Uribe’s strategy enabled his successor, Juan Manuel Santos, to negotiate an agreement in 2016 under which the much-weakened FARC demobilized and disarmed. It was a historic achievement that offered a blueprint for the state to occupy the third of the country it didn’t control and open it up for economic development.

Yet the politicians squandered the opportunity. Uribe had myopically campaigned against the agreement, and Santos allowed coca cultivation to boom in his last two years in office. The next president, Iván Duque, a protégé of Uribe, did the minimum to implement the agreement while politicizing the armed forces.

Petro comes to power

And then in 2022 came Gustavo Petro, a populist leftist whose formative political experience was as a clandestine political organizer for M-19, a nationalist guerrilla movement. Petro offered to remake the country when what it needed was incremental reform and better administration. Brushing aside the 2016 agreement, he promised “total peace,” offering to negotiate with the remaining armed groups: the ELN guerrillas; two splinters from the FARC; the Clan del Golfo, a successor to the paramilitaries; and other smaller outfits. These groups derive their income from organized crime. To many analysts, “total peace” was at best naïve and at worst a bid to co-opt criminal allies.

Petro offered unconditional ceasefires at the start rather than the conclusion of talks. Three years on, the illegal armed groups have grown. According to think tank Fundación Core, by the end of 2024 the Clan del Golfo operated in 238 municipalities, up from 200 in 2022. It has also doubled in strength since 2018 and now has over 7,500 operatives. The ELN has grown, too, and is now making lethal use of drones. In January it killed more than 80 members of a rival group in a large-scale operation in Catatumbo, on the Venezuelan border, that forced 20,000 civilians to flee. The FARC dissident outfits have mushroomed to four, their members doubling on Petro’s watch to almost 8,000. According to Fundación Ideas para la Paz, another think tank, the year to July 2025 saw the highest level of armed conflict since 2010, with 295 attacks on the security forces.

While illegal armed groups are stronger, the armed forces are weaker. Their headcount has fallen from a peak of 242,000 in 2012 to 181,000. Their operational capacity has shriveled much more. Military spending has increased under Petro, but much has gone on increasing the stipend paid to conscripts—a politically popular move. Meanwhile, two-fifths of the military helicopter fleet is grounded for lack of spares or maintenance, and, according to military analyst Eduardo Pizarro of Contexto, security forces no longer have the capacity to stage two airborne operations at the same time.

A chaotic landscape

Petro’s security policy is confused. His first defense minister, Iván Velásquez, was a human-rights prosecutor with no military experience whose first action was to purge almost 50 army and police commanders. He told me he was implementing Petro’s instruction to cleanse corruption and abuse. Critics argue he cleared out decades of experience and knowledge. Police intelligence has been gutted. Now, in the wake of the latest attacks, Petro has decided that the groups he has been negotiating with are terrorist organizations that should be pursued internationally.

Meanwhile, Colombia’s political climate has deteriorated in parallel with security. The sentencing of Álvaro Uribe in the witness tampering case to 12 years’ imprisonment, which he is appealing, has further polarized the campaign for next year’s presidential election.

And Petro has not given up on trying to force a constituent assembly—the last thing Colombia needs. Rather, the country needs to relearn the lessons of its past success. It is not too late. But only a muscular and intelligent security strategy can lay lasting foundations for peace and the rule of law.