“I am the one who is going to govern,” declared Claudia Sheinbaum, Mexico’s president-elect, shortly before her June election victory. But the question remains as to just how she will govern, and how she might distinguish herself from talismanic incumbent Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO). A first key test will be the secondary regulations of the recently approved judicial reform that are soon to be discussed and begin their implementation this year.

Given her background as a scientist focused on energy and the environment, Sheinbaum is often described as a technocrat. Many of her policy proposals reflect this, and it seems that her government will be more pragmatic and less steeped in populism than AMLO’s. At the same time, her close relationship with AMLO and her enduring support for some of his more troubling policies such as judicial reform suggest her government will take shape as a new blend—one that could be deemed “techno-populist.”

What does that mean exactly? This hybrid style of governing will attempt to maintain the popular social programs and jingoistic postures that characterized AMLO’s government. But to fund continued spending on welfare and infrastructure, Sheinbaum will diverge from AMLO’s handling of the economy, betting on a renewed relationship with the private sector to boost growth. Whereas AMLO pushed more state and less market, Sheinbaum is likely to push both, more state and more market. That is not as much of a contradiction as it may initially seem.

The science and tech sectors, for example, which were neglected under AMLO, will feel this change almost immediately. Sheinbaum plans to create a Ministry for Science, Humanities, Technology and Innovation headed by a top scientist, whereas AMLO dismantled the Conahcyt, a similar institution. And Sheinbaum seems determined to treat energy differently. AMLO poured almost $70 billion into state-owned oil behemoth Pemex and constrained renewables development, while Sheinbaum plans to use a form of public-private partnerships (PPPs), probably under a different name, to boost green technology. In April, she unveiled a $13.6 billion investment proposal for solar, wind and hydroelectric projects and the expansion of the electrical grid.

Sheinbaum also seeks to use partnerships with the private sector to digitize key areas of government, including customs, taxes and health care. The plan to roll out single digital medical records and online medical appointments for individuals, for example, demonstrates faith in a focus on efficiency. Overall, it’s an approach that may result in opportunities for both large companies operating in Mexico as well as smaller ones.

Still, it’s unclear whether these kinds of moves will outweigh her Morena party’s penchant for undemocratic power grabs, and the accumulated years that AMLO spent undermining independent institutions and the basic checks and balances that ensure the rule of law. AMLO will leave office extremely popular, with over 70% approval, and cast a long shadow. Meanwhile, Sheinbaum can claim one of the strongest mandates in modern history after winning the highest vote count ever in Mexico, although not as high as the “over-representation” that gave her a bulky number of deputies. Perhaps more importantly, she will inherit expanded presidential powers as well as a new supermajority in both chambers of the legislature—not to mention unprecedented influence over the justice system in the wake of this month’s massive judicial reform, AMLO’s latest effort to tighten Morena’s grip on every branch of the state with, in this case, Claudia Sheinbaum’s support.

Sheinbaum’s next steps

How far and how fast she hopes to go in executing her agenda will become clearer when next year’s budget is presented on November 15. Despite the broad powers Sheinbaum will have, she will be constrained by the results of her predecessor’s fiscal decisions. AMLO ran up the deficit from 2.1% in 2018 to an estimated 5.9% at the close of 2024, the highest level in over 30 years. Over that period, he increased cash handouts from $8 billion to $30 billion—it is no coincidence that this record high occurred during an election year. He also increased the minimum wage by 150% through presidential decree instead of productivity improvements, and showered billions on the Dos Bocas refinery, which cost more than double original estimates, and the Maya Train, itself already 250% over budget.

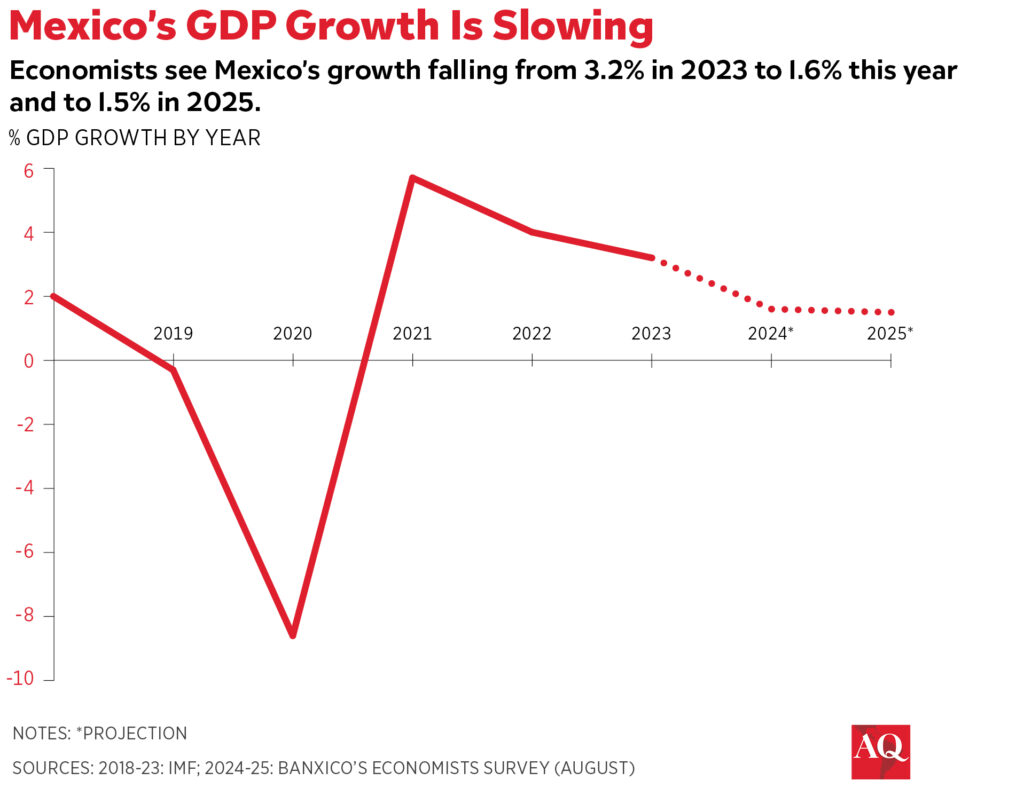

Unsurprisingly, growth is slowing; Mexico’s Central Bank lowered its 2024 forecast to 1.5% and next year’s to 1.2%. Sheinbaum knows that she can only continue to spend as promised on welfare and infrastructure by growing the economy, especially as she has seemingly ruled out raising taxes.

On the positive side, Mexico’s broader debt-to-GDP ratio of 50% is—for now—relatively sustainable. And Sheinbaum may be able to relieve some fiscal pressure by a much-needed change of course on Pemex. If it is forced to focus on profitability and Sheinbaum can reduce the government largesse flowing into it, this will provide some breathing room.

But to make meaningful gains, Sheinbaum will have to repair the government’s relationship with the private sector and encourage private growth and investment. And she will have to do that sooner than later. This will require her to attempt to assuage concern over the recently approved judicial reform, which has spooked domestic and international investors who seek stability and certainty and are uncomfortable with a judiciary full of government loyalists.

As always, the devil is in the details of implementation. Justified enormous concern may ebb somewhat if Morena manages to implement the reform gradually and carefully, particularly in relation to features such as independence, career and selection of judges. Regardless, the potential long-term consequences of the reform will loom over the credit ratings of its sovereign debt and the 2026 renegotiation of Mexico’s USMCA trade agreement with the U.S. and Canada, likely hurting Mexico’s standing.

The Sheinbaum sexenio won’t be entirely populist or entirely technocratic. Instead, her “techno-populism” hybrid is likely to mean much more state, more market and more technology all at once. She aims to expand social programs, fund infrastructure, and maintain Morena’s popularity, paying for it by boosting growth, improving private sector confidence, and making government more efficient.

There is ample room for Sheinbaum to make the next administration more technocratic and more efficient. But even if such improvements materialize, it’s unclear whether they can overcome the weight of a state bereft of meaningful checks and balances and a severely questioned new framework for the rule of law.