This article has been updated.

MEXICO CITY — Mexico’s growing ties with China have raised concerns in the U.S. and Canada. These countries fear that Mexico could serve as a “backdoor” for Chinese goods entering the U.S. under USMCA’s preferential trade terms. And with President-elect Donald Trump preparing to return to the White House and a review of the USMCA next year, more scrutiny is coming.

Mexico’s trade relationship with China has placed it at the heart of North America’s simmering economic and geopolitical tensions. What is the actual state of China’s economic relationship with Mexico?

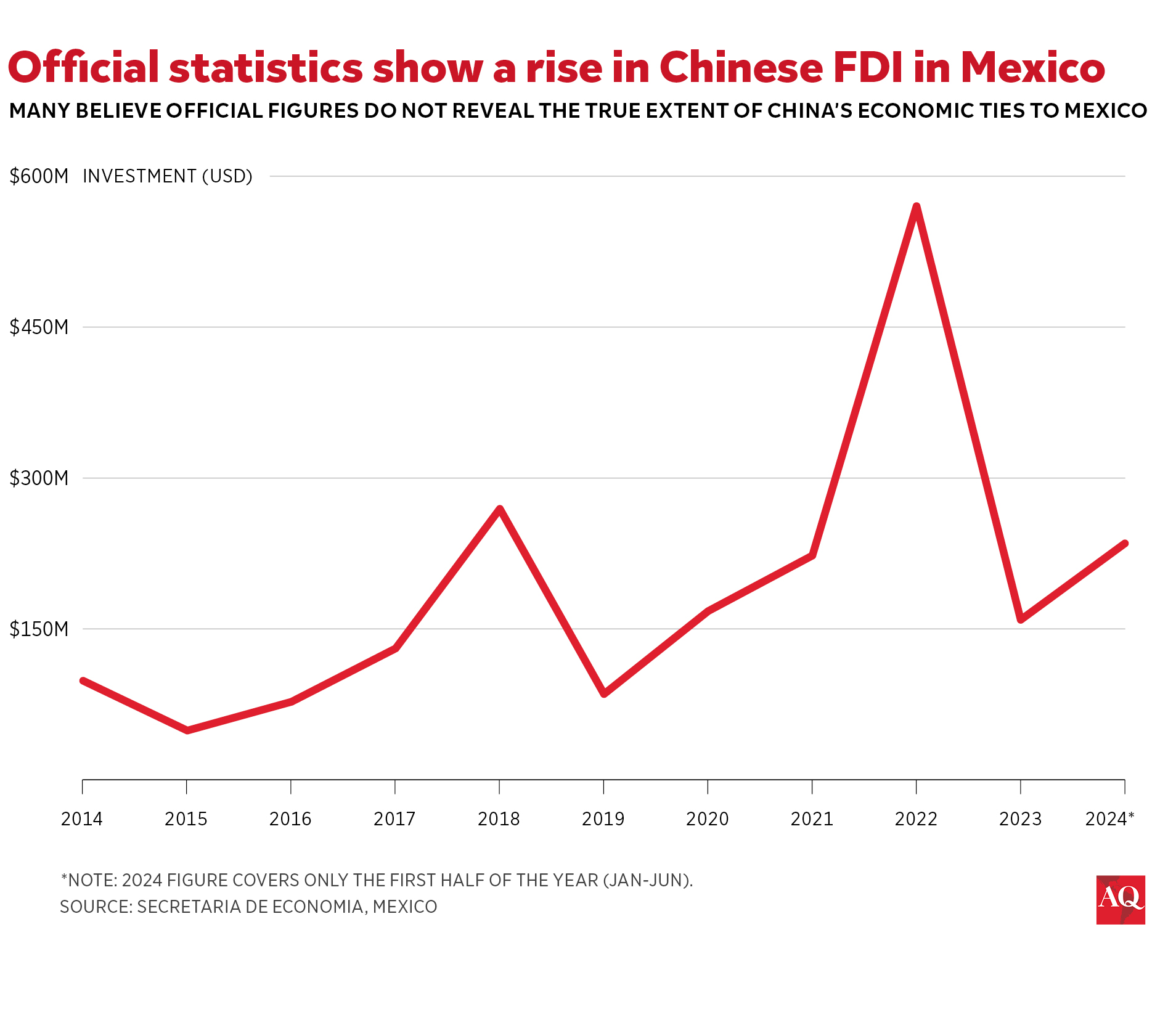

Over the past several years, Chinese companies have significantly expanded their presence in Mexico, using the country as a gateway to the North American market. Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Mexico has grown at an average rate of 50% since 2018. Last year, a remarkable 60% surge in shipments from China raised eyebrows, as did China’s rapid inroads into the Mexican car market, where it now sells a fifth of all new automobiles. Chinese state-owned enterprises are involved in infrastructure-building projects across the country, and China has provided considerable amounts of surveillance equipment.

There’s also reason to believe that the true extent of China’s economic ties to Mexico are not captured in official statistics. All of this makes for vulnerability for Mexico—but Claudia Sheinbaum’s administration can make the best of it by insisting on transparency in its relationship with China going forward.

Rising economic ties between China and Mexico

A recent Kearney report highlighted a striking 60% year-on-year surge in Chinese container shipments to Mexico between 2023 and 2024. Peter Sand, chief analyst at Xeneta, an Oslo-based firm specializing in air and sea freight market analysis, characterized this dynamic as the fastest-growing trade route in the world right now. This growing trade relationship is underscored by increased Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Mexico, which has seen nearly two thirds of its $2.48 billion total occurring since 2018.

The trade relationship between Mexico and China has experienced unprecedented growth. Over the last five years, Chinese exports to Mexico have increased by an annualized rate of 10.6%. In 2023, Mexico exported $8 billion worth of goods to China, primarily minerals and machinery, while importing $101.8 billion, resulting in a trade deficit of $93.8 billion.

Mexico’s industrial parks have become hubs for Chinese firms, including state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Over the past three years, the number of Chinese companies in these parks has doubled, particularly in sectors hit by U.S. tariffs, such as automotive, electronics, and consumer goods. Notably, Hofusan Industrial Park located in the bordering state of Nuevo León, hosts over 30 Chinese companies.

Illustrating China’s growing influence in critical sectors of Mexico’s economy, SOEs are also involved in the nation’s infrastructure projects, such as the Xochimilco-Taxqueña light rail system manufactured by China Railway Construction Corporation (CRCC), and upgrades to metro systems in Mexico City and Monterrey. Furthermore, two of Mexico’s three major airlines lease aircraft through CDB Aviation, an Irish subsidiary wholly owned by China Development Bank Financial Leasing Co.

Hardware and software concerns

Among the industries where China could expand its presence in Mexico, few are as strategically significant—or as politically sensitive—as the automotive sector. As a global leader in car manufacturing, Mexico produces 3.5 million vehicles annually, with three-quarters exported to the U.S.

In 2023, Chinese firms announced $2.72 billion in automotive investments, making up 72% of all Chinese FDI in Mexico that year. This increase is mainly driven by parts manufacturers, such as ZC Rubber, which unveiled a $600 million investment in 2024. Chinese automotive groups are investing over $1 billion at Alianza Industrial Park in Coahuila, 250 km from the U.S. border. In September, the Chinese electric car maker BYD denied reports of pausing plans for a Mexican plant.

Chinese automakers have established a strong foothold in the Mexican market, accounting for one-fifth of new cars sold in the country last year, a sharp rise from just 4% in 2020, in a market where 36 brands compete for the consumer’s favor. In 2023, Mexico became the second-largest importer of Chinese vehicles globally, trailing only Russia.

These trends have prompted distress in Washington about the security and economic implications of Chinese automotive dominance in the region.

During his campaign, Trump suggested imposing tariffs of 200% to 500% on vehicles imported from Mexico, stating, “I don’t want them hurting our car companies.” A key concern was the growing presence of Chinese investment and components in vehicles manufactured in Mexico and exported to the U.S. President Biden had previously proposed banning Chinese hardware and software in connected cars on U.S. roads—a move that would block Chinese-made vehicles from entering the U.S. via Mexico.

The digital economy is another area where Mexico’s relationship with China is under scrutiny. Notably, ten firms identified by the U.S. Department of Defense as linked to China’s military apparatus—including Huawei, Dahua and Hikvision—are active in Mexico.

Despite U.S. bans, Huawei has entrenched itself as a key player in the nation’s telecommunications sector, while Dahua and Hikvision supply surveillance equipment, including for public security in border states like Chihuahua and Coahuila. This has heightened tensions between Mexico and its northern neighbors, as Chinese penetration in critical sectors like technology and communications poses potential security risks.

A red wave below the surface

The official statistics on Chinese investment in Mexico may understate the true scale of economic engagement. Rhodium Group’s analysis suggests that Chinese direct investment could be over six times higher than reported by Mexican and Chinese authorities. Many investments are channeled through offshore hubs like Hong Kong, further complicating transparency. For instance, China Communications Construction Company Limited (CCCC), an SOE blacklisted by the World Bank for fraudulent practices, secured a contract for Mexico’s flagship infrastructure project, the Mayan Train, yet its investment does not appear in official records.

Another significant gap in information pertains not to Chinese investments but to Chinese loans in strategic projects. China Construction Bank has increasingly made inroads into strategic sectors in Mexico, such as aviation and infrastructure. However, data on these activities remains fragmented and largely inaccessible to the public.

Turning a challenge into an opportunity for President Sheinbaum

Sheinbaum’s administration has taken steps to reassure Mexico’s main trading partners, ending the country’s historical strategic ambiguity toward China. Mexico has tightened oversight of Chinese steel and aluminum exports and raised tariffs on imports from non-USMCA countries. Sheinbaum introduced Plan Mexico to boost domestic production of goods currently imported from China, and in a recent speech in Nuevo Laredo, she emphasized the USMCA’s role in countering economic competition from China.

However, Mexico must do more to reduce its trade deficit with China by promoting higher-value exports, and it must prioritize transparency in its economic ties with China. Stronger regulatory oversight, accurate reporting of foreign investments, and better alignment between federal and state governments on China could help ease U.S. and Canadian concerns. The country has an opportunity to position itself as a regional manufacturing hub, replacing China in supply chains and attracting investment from East and West. This requires a strategic focus on sectors like automotive and electronics, where Mexico already has a competitive edge.

The 2026 USMCA review will mark a critical juncture for Mexico’s trade strategy as it seeks to strengthen its position as a reliable partner to the U.S. and Canada. Navigating the complexities of its economic ties with China—including addressing transparency concerns—will demand a delicate balance. By aligning closely with North American priorities and leveraging growth opportunities, Mexico can effectively chart a course through the intertwined challenges of global trade and geopolitics.

This article was updated on January 16 to add 2023 Mexico -China trade data on the sixth paragraph.