SANTIAGO — Last week, Chile’s Congress broke a decade-long impasse and approved a pension reform, a flashpoint in Chilean politics. The green light represents a legislative victory for President Gabriel Boric in the last full year of his administration. However, while Boric can claim that his government will leave a meaningful legacy, he’s giving up a central point in his reform agenda: the elimination of the Pension Fund Administrators (AFPs).

The approved reform differs significantly from the government’s initial proposal submitted in November 2022, which sought to repeal the system created by the military dictatorship in 1981. It was an ambitious, complete overhaul of the system, difficult to pass in its original form. The proposal sought to abolish the AFPs and establish a more prominent role for the state in managing social security contributions. The opposition raised complaints about the proposal’s scope, labor costs, and long-term sustainability.

However, the parties came to terms, pressed by Chile’s political and economic limitations. Overcoming legislative gridlock in today’s increasingly fragmented and polarized political climate required compromises from both sides. Two previous administrations attempted and failed to deliver a reform of this kind.

Since Chile became the first country to implement an individual capitalization system, pensions have remained at the core of political disagreements. Due to the significant number of workers who do not make regular contributions and a retirement age (65 for men and 60 for women) that has remained unchanged for nearly a century, a large segment of the population has received low pensions. These tensions fueled the large-scale No+AFP protest movement almost a decade ago and the push for massive pension fund withdrawals during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The new reform is intended to correct the current imbalances. Once Boric signs it into law, the mandatory contribution rate will gradually rise from 10% to 16% of the worker’s salary, pensions for women will improve, and the commissions charged by AFPs eventually will be reduced. And the Boric administration is likely to tout this achievement ahead of November’s general elections.

While pensions will improve, with changes set to take effect for most Chileans next year, the reform carries a high fiscal cost. Chile faces a challenging economic outlook, and the reform undoubtedly is a step in the right direction. However, it makes clear that Chile will need to take additional measures to improve the well-being of its citizens.

The path to consensus

While there had long been broad consensus on the need to increase the contribution rate from 10% to 16%, the government’s initial stance was that this additional 6% should go to a pay-as-you-go system. The opposition insisted that the full six points should be allocated to the existing capitalization system. However, there was some agreement on the need for changes in the industry, aiming to increase competition among administrators to reduce management fees, which led to high profits for the AFPs.

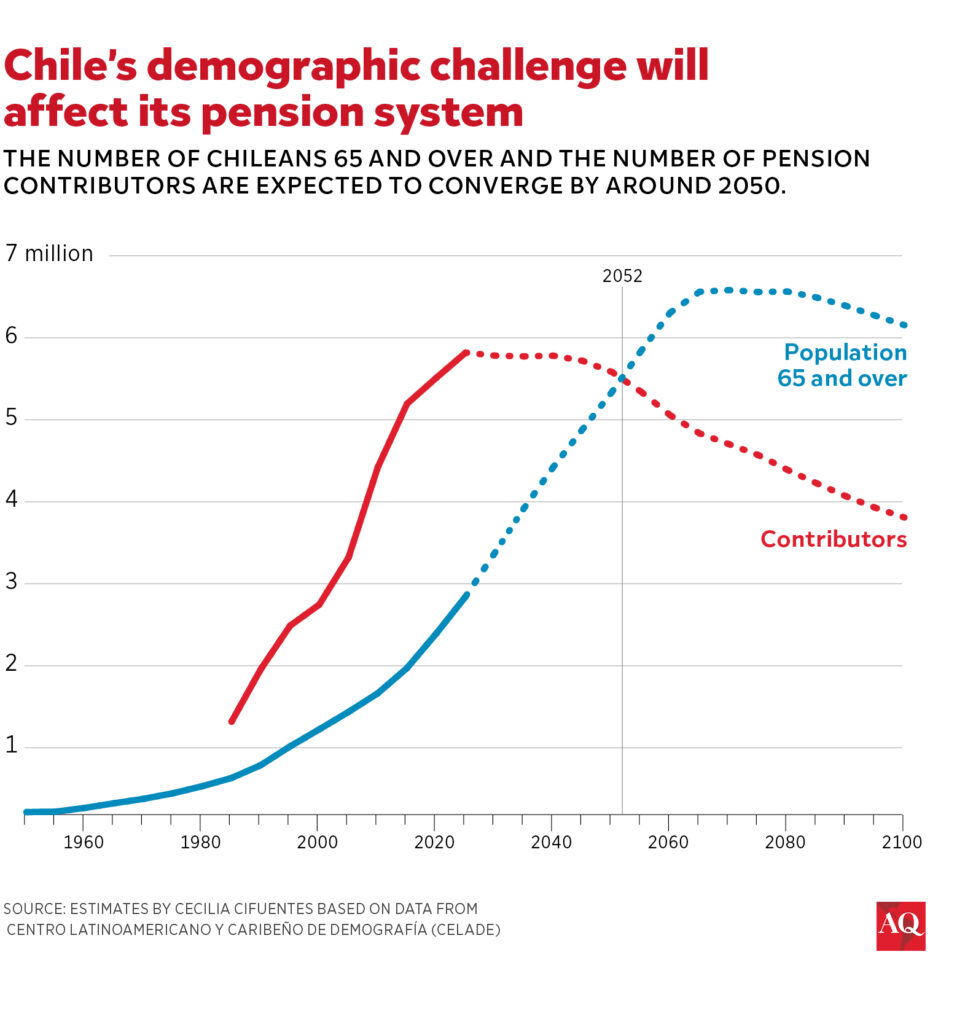

Studies on the impact of the Universal Guaranteed Pension (PGU), which started to be paid in 2022 and more than tripled the state’s contribution to social security through its solidarity pillar, showed that replacement rates for the vast majority of retirees were very high, exceeding 70%. These analyses, including those conducted by the government, noted that future replacement rates would be lower due to Chile’s aging population. This indicated that establishing a pay-as-you-go system was not only financially unsustainable due to demographic trends, but also intergenerationally unfair.

Following the reform, the system will remain essentially one of individual capitalization, and private entities such as AFPs will continue managing workers’ savings. The opposition had to accept a greater role for the state in the system, through the creation of the Autonomous Social Protection Fund.

What the reform entails

The pension reform increases the contribution rate by seven percentage points, which will be paid by employers. To mitigate the impact on labor costs, this increase will be implemented over a period of nine to 11 years, depending on the fiscal situation. Of this increase, 4.5 percentage points will go directly to current capitalization accounts managed by the AFPs, adding to the existing 10%.

To improve current pensions, contributors will allocate 1.5 percentage points to a loan to a State Protection Fund, which has a government guarantee and whose financial management will be auctioned to private entities. This loan will be recorded in individual savings accounts and repaid upon retirement in 20 years. Finally, there will be a 1% contribution dedicated to improving women’s pensions, with an adjustment for their longer life expectancy compared to men.

These benefits will only be distributed to individuals who have contributed for at least 10 years in the case of women and 20 years for men. Additionally, the benefit for women due to longer life expectancy will be granted only if they retire at the same age as men, at 65 years old. In this way, while new benefits were created to improve current pensions, incentives were also established to increase contributions. This is particularly important because the main cause of low pensions is Chile’s roughly 27% informal employment rate.

AFPs will continue to exist in a very similar form and will manage a significantly larger amount of resources. Today, the AFPs manage $185 billion, an amount that is expected to grow by approximately 70% over the next decade following the reform. However, the AFP industry’s barriers to entry will be reduced, investment policies will be modernized, and it will be mandated that every two years, 10% of affiliates’ stock will be auctioned to the administrator that offers the lowest fees. Affiliates included in the auctioned stock will be free to reject the change of administrator at any time. Additionally, rewards and penalties will be established for administrators based on the returns they achieve.

The risks

Ultimately, the agreement improves current and future pensions while creating incentives to increase contributions. However, the reform’s fiscal cost is high (1.7% of GDP, or $5 billion annually) mainly due to the state’s role as an employer. Approximately 13% of total employment in Chile is in the public sector.

Moreover, in an economy struggling to grow at just 2% per year, the increase in labor costs is challenging for businesses to take on, potentially resulting in a negative effect on formal employment. In 2024, unemployment stood at 8.5%, more than one percentage point higher than the pre-pandemic level in 2019.

If the reform is enacted in March, a small group of retirees would see an improvement in their pensions by September, while the vast majority would experience an increase in 2026, after the presidential and legislative elections in November. Even though the final version of the reform aligns more closely with right-wing principles, this sector showed a higher degree of divisiveness during the approval process, whereas the left embraced it as a step toward the social security model they advocate despite its modest scope. In any case, the reform’s political effects are likely to fade in the next few months.

Politics aside, the reform has resulted in a new technical consensus: Chile must achieve higher growth rates, essential for sustainably providing greater social protection.