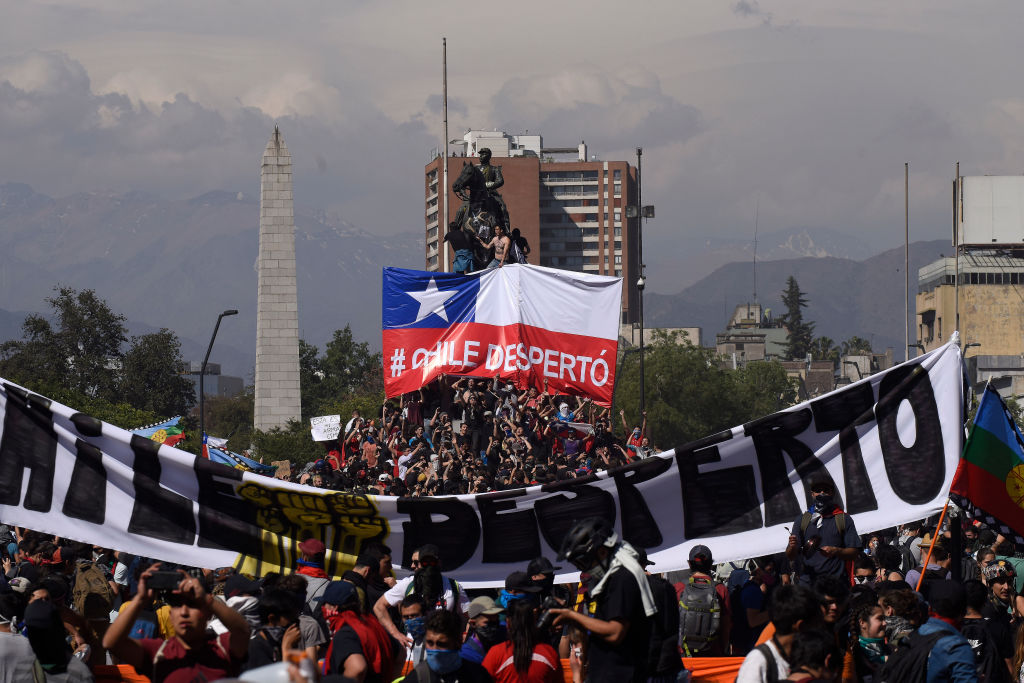

SANTIAGO — It is not an exaggeration to call the events of October 2019 in Chile a revolution, or at least an attempted one. The scale of the social and political changes demanded in large-scale protests against the status quo would have represented a transformation of the country on the level of the “social revolutions” that theorist Theda Skocpol discusses in a renowned 1979 book.

And those changes might have materialized, had the first constitutional proposal been approved in September 2022. But that did not occur. The Chilean people twice rejected extreme constitutional proposals, the second one emerging from the right—and as a result, it’s easy to think that Chile is back to where it started.

But even failed revolutions do not quite lead back to their starting point. That seems to be the case in Chile. A process that has yet to conclude was set in motion, but the country is in a very different place. Five years on, it is worth asking what happened to the October Revolution.

History may provide models for our understanding. Alexis de Tocqueville saw the French Revolution as the consequence, in part, of the failure of France’s political system to catch up to social changes: namely, the rise of a new middle class, the bourgeoisie. But perhaps the lesson of the French Revolution is not that revolutions inevitably turn against themselves but rather that they become processes with uncertain outcomes.

A political off-ramp

In Chile, after the explosion of October 2019, events conspired to extinguish the flame. Roughly a month in, and in the face of mounting violence, former President Sebastián Piñera concluded that the country needed a political off-ramp. He asked the political parties to come together to negotiate a constitutional proposal, which was achieved on November 15, 2019. This channeled much of the energy away from the street and towards the negotiating table. As COVID-19 made continued protest impossible, the country carried out the terms of the November 15 agreement. As we now know, it all came to nothing.

Three years of constitutional negotiation, conventions, and referendums led to two disappointing proposals, one more extreme than the other. The voters’ rejection not only dashed hopes for progress on the constitutional issue, it derailed the governing program for the new Gabriel Boric administration, which was convinced that a new charter would open an institutional path towards a new economic, political, and social model for Chile. The rejection led many to conclude that, unlike the popular protest slogan of “Chile has changed,” the country, in fact, remained pretty much the same and that the demands made on the streets no longer mattered.

But this is also the wrong conclusion. Lost in the violence and heady revolutionary rhetoric were real social problems and economic challenges: a segregated educational system, inadequate pensions, and the high cost of essential products. Like the French Revolution, Chile’s October Revolution was, at its core, the consequence of a political system that was too blind to see how much society had evolved and too inflexible to evolve with it. The fact that these demands were later hijacked by organized groups who had long called for constitutional change, or that President Piñera thought that the October Revolution had been orchestrated by the Maduro regime, hid the importance of the original series of demands. Indeed, looking back, it is not hard to see how economic stagnation led to an explosion.

Although investment and other macroeconomic indicators fell after the October Revolution, stagnation had set in around 2010, when trust in government collapsed. A few years later, student protests, and President Michelle Bachelet’s measures to respond to them—including higher taxes and education reform—resulted in a noticeable drop in growth and investment. The “Latin American Puma” of the early 2000s had been tamed, with GDP growth struggling to return to annual expansion rates of 3%, much less than the 5-7% of the boom years.

But amazingly, the idea set in that this did not matter. For some on Chile’s new left, global trade was a dark corporate plot, and degrowth seemed like an attractive option. Gabriel Boric dreamed of Chile becoming the place where neoliberalism came to die. Much of this hubris has been diminished by the weight of government, but the internal tensions between the Communist Party and other government partners, or the administration’s most recent proposal to transform higher education, show that there are elements within Boric’s administration that hope to use the 16 months it has left to leave a revolutionary mark.

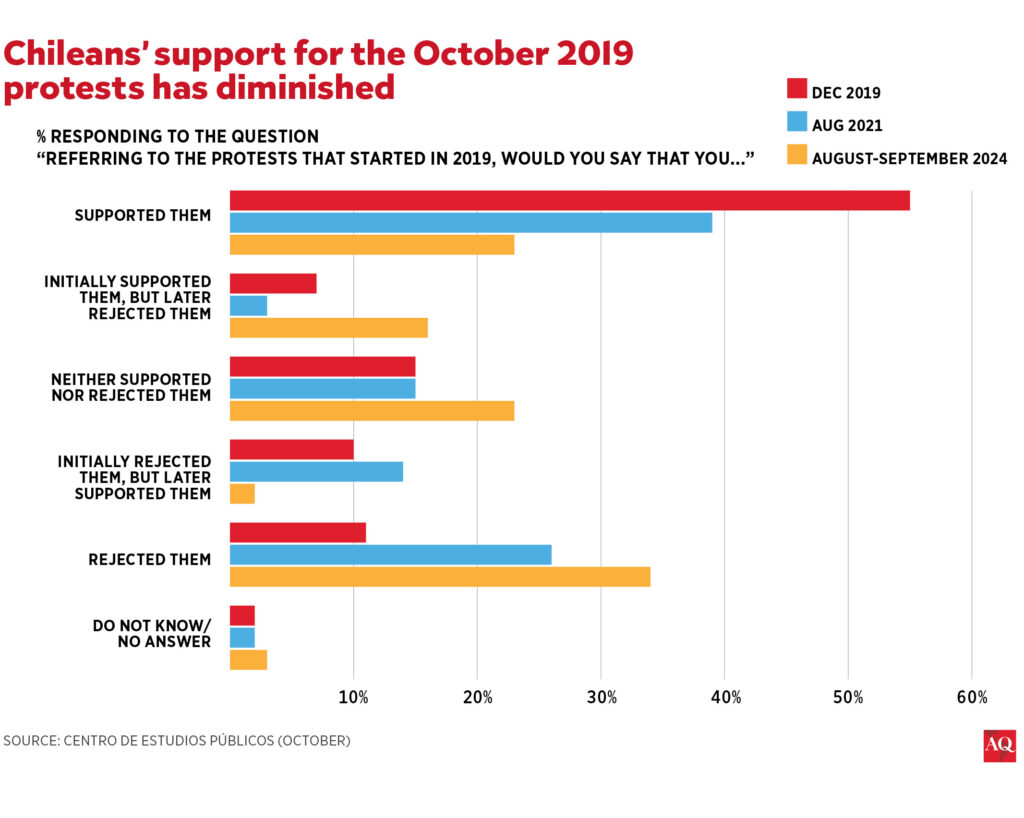

Where does all of this leave Chile now? According to a recent Centro de Estudios Públicos poll, only 17% of those asked said that the October Revolution had been a positive influence on Chilean society. Even more amazingly, 23% claim to have supported the protests, whereas at the time, 55% were in favor. In other words, not only have Chileans reconsidered in hindsight, but they have also conveniently forgotten what their stance on the protests was in the first place. Today, crime and drug gangs are the primary concern, and as a result, people clamor for more police, not for defunding them, less violence, and not using violence to justify political objectives.

Five years after the October Revolution, even though the basic social problems remain, they’ve been overtaken by more basic worries about public safety. In October 2019, Chile thought it was about to become Scandinavia, but today, many appear to be looking more toward El Salvador as a model.