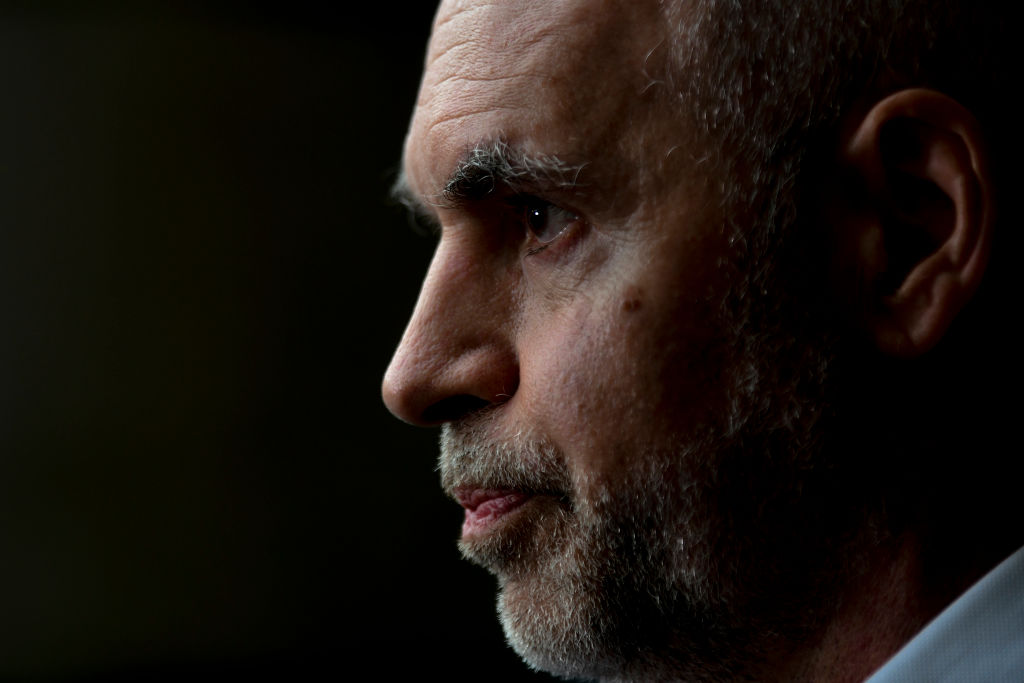

BUENOS AIRES – Last month, The Economist said Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, the mayor of Argentina’s capital city and a candidate in next year’s presidential election, lacks “pizzazz.” They meant it as a compliment.

Argentina’s politics are notoriously volatile, fueled by a partisan rivalry so deep and persistent it is known as the grieta or “fissure.” But the country’s moderates see things differently. They celebrate antigrieta candidates and their pragmatic positions, sometimes described as “Central Korea” (neither North or South) or as “neither River nor Boca,” the country’s two most popular soccer clubs.

Rodríguez Larreta, the two-term mayor of Buenos Aires, is firmly in the antigrieta camp. Earlier this month, he visited Washington, where he said he would build a diverse and durable coalition to end Argentina’s chronic political seesawing. He might have lacked pizzazz but his audiences, including investors, seemed to welcome his promise of bipartisanship, or at least his commitment to lower the political temperature by a few degrees.

In Argentina, there is skepticism that Rodríguez Larreta’s pragmatism will be compelling to voters accustomed to combative figures like Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, a former two-term president and now the country’s vice president.

But there is also evidence many Argentines think charisma is overrated. For years, polls have shown Rodríguez Larreta to be the country’s most popular political figure. Fernández de Kirchner, by contrast, is widely disliked. Last year, the mayor’s allies—including his vice mayor, Diego Santilli—scored important victories in the legislative primaries over candidates supported by his more conservative rival, Patricia Bullrich, president of Rodríguez Larreta’s Republican Proposal (PRO) party.

These days, partisanship is on pause in Buenos Aires, as Argentines join together to cheer on the national soccer team, many wearing the same Number 10 Lionel Messi jersey. “Vamos Argentina” placards outnumber the “Todos con Cristina” banners that first went up in August during the vice president’s corruption trial and proliferated after she survived an assassination attempt.

But even before the World Cup, there were signs that Argentines had tired of political warfare. In the Radical party (UCR)—the PRO’s partner in the opposition Juntos por el Cambio coalition— the most prominent figures are lawmaker Facundo Manes and Jujuy Governor Gerardo Morales, both moderates. In the governing party, the most powerful Peronist is moderate Finance Minister Sergio Massa. Outside the capital, the most influential Peronist is arguably Córdoba Governor Juan Schiaretti, an antigrieta icon. Historically, Peronism has been famous for its ideological flexibility. That remains true for many of its likely future leaders, such as San Juan Governor Sergio Uñac and former Salta Governor Juan Manuel Urtubey.

Fernández de Kirchner has not moved to the center. Nor has her son, Máximo Kirchner, a lawmaker and founder of the La Cámpora youth movement. Nor has her protégé, Buenos Aires Governor Axel Kicillof. Still, the vice president is cultivating a more moderate image for her ally Eduardo “Wado” de Pedro, the interior minister and a potential presidential candidate who recently visited the United States. She used the same strategy in 2019, when she chose a moderate Peronist, Alberto Fernández, to compete for the presidency.

It is possible that politics in Argentina will radicalize again—in line with the broader regional trend. The most recent elections in Peru, Chile and Colombia all pointed to a shrinking political center. In Argentina, a decade of economic stagnation and recurrent crisis have profoundly soured the public mood and eroded trust in public institutions and traditional political parties. Libertarian lawmaker Javier Milei is captivating independent voters with broadsides against the “political caste,” echoing slogans shouted by protestors during Argentina’s 2001-2002 economic collapse. Milei has strongly criticized Rodríguez Larreta, sometimes in vulgar terms.

Conditions are ripe for populist rage. Inflation is approaching 100% this year. Economic recovery has slowed. Hard currency reserves are low, prompting import restrictions. Protests are frequent, snarling downtown traffic. There are countless potential triggers for another economic or political crisis, such as a failure of Argentina’s program with the IMF or a rupture between Fernández de Kirchner and the president or finance minister. The situation is touch and go, with analysts debating whether or not the president will “land the plane” or see it crash and burn before he completes his term.

A crisis would expand support for polarizing candidates. “Don’t underestimate public anger,” pollster Alejandro Catterberg told AQ.

Even absent a breakdown, Rodríguez Larreta’s star could fade, opening the door for a more divisive figure. As Sergio Massa recently put it, “Today’s candidate is tomorrow’s corpse.” Juntos por el Cambio has not yet coalesced around Rodríguez Larreta; Bullrich is still jockeying for control of the coalition, and former President Mauricio Macri, who has become more conservative, is flirting with another presidential run.

But for now, Argentina’s moderates maintain robust support as the country heads towards the 2023 election. Almost half of Argentines approve of Massa’s pragmatic performance as finance minister, for example, compared to the 31% approval rating for the divisive Fernández de Kirchner, according to Poliarquía. For his part, Rodríguez Larreta is still widely considered the presidential frontrunner, seemingly buoyed by his pledges to build bridges across this country’s vast political and social divides.

—

Gedan is acting director at the Wilson Center’s Latin American Program.