Since Brazil co-founded the BRICS in 2009, Brazilian analysts and politicians have largely agreed that membership brought tangible benefits to the country—including closer ties to China. But as this year’s summit approaches, the costs are adding up. The meeting in Kazan, Russia, will occur as the invasion of Ukraine, more than halfway through its third year, continues to cloud Vladimir Putin’s reputation.

BRICS membership (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) helped solidify Brazil’s status as an emerging power, a narrative that has held up remarkably well despite economic stagnation during the last decade. It also guaranteed Brazilian leaders regular facetime with China’s political leadership and bureaucracy, which became the country’s top trading partner in 2009.

The countless intra-BRICS meetings on areas ranging from defense and health to education and the environment helped Brazil’s bureaucracy, largely ignorant about China until recently, adapt to a less Western-centric world. Perhaps most importantly, however—and often overlooked by Western analysts—is that Brazil found common cause with other BRICS members in seeking to actively shape the transition towards multipolarity, which they regard not only as inevitable but also desirable and a development that will help constrain Washington.

Meanwhile, the costs of BRICS membership were largely seen as negligible, so neither center-right president Michel Temer (2016-18) nor far-right president Jair Bolsonaro (2019-22) questioned Brazil’s membership. On the contrary, by the end of his government, Bolsonaro was a pariah in most of the West, but thanks to the BRICS grouping, he avoided complete diplomatic isolation. After all, it was only during encounters with fellow BRICS leaders that the former right-wing president could be sure not to face uncomfortable questions about his handling of the pandemic, deforestation or his unfounded allegations about electoral fraud.

Brazil hits a BRICS wall

Recent developments in the BRICS grouping, however, have the potential to undermine this relatively broad consensus in Brazil vis-à-vis the benefits of membership. Until last year, Brazil had, along with India, successfully prevented the bloc’s expansion, promoted by Beijing since 2017. Both Brasília and Delhi feared a loss of the grouping’s exclusivity and a loss of capacity to control intra-BRICS dynamics, having worked to fend off efforts by China and Russia to include anti-Western language in the summit declarations. Symbolizing the growing rift between an anti-Western bloc and another that opts for multi-alignment (or non-alignment), Russia often seeks to portray BRICS as a counterweight to the G7, while President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva likes to insist that BRICS is “not against anyone.”

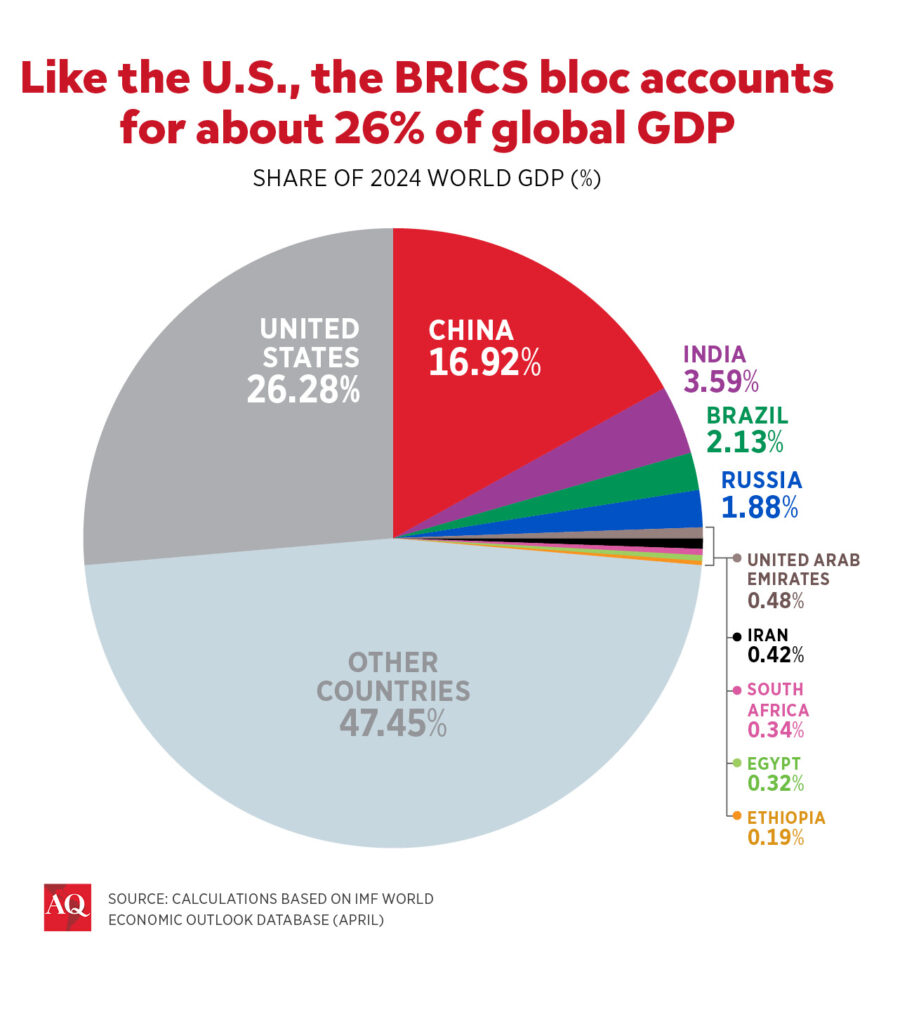

Yet during last year’s summit in South Africa, China ran out of patience and, with Russian support, not only pushed through expansion but also ignored Brazil’s request not to include explicitly anti-Western countries such as Iran. Due to Argentina’s decision to decline the invitation to join BRICS, democracies, which had held a 3-2 majority within the grouping until last year, are now in the minority after the accession of Iran, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Ethiopia. Saudi Arabia, which has also been invited, has yet to publicly announce whether it will join and is largely expected to wait until the upcoming U.S. elections. BRICS now increasingly looks like a pillar of a Sino-centric order Beijing seeks to establish rather than a grouping that is “not against anyone.”

The Russian equation

It does not come as a surprise that Russia’s president will use the upcoming summit in Kazan to show that the West has failed to isolate him on the world stage in the aftermath of the brutal invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. In the same way, the summit can be seen as a foreign policy win for Iran, a major supplier of drones used by Russia in Ukraine and which is currently involved in a tense stand-off in the Middle East. It is highly unlikely that Brazil and India (and, to a lesser degree, South Africa), which seek to craft a strategy of equidistance between the major centers of power and do not wish to downgrade their ties to the West, will be able to entirely avoid this BRICS summit’s strongly anti-Western narrative.

None of this will lead Brazil to abandon the grouping abruptly. Yet behind closed doors, it is now common to hear Brazilian diplomats express concern about Brazil’s diminishing capacity to control intra-BRICS dynamics and to use the outfit to its benefits. A similar apprehension is palpable in India, where the government does little to hide its discomfort with China’s growing dominance of the grouping. During last year’s summit, Narendra Modi had initially decided to participate only virtually, before changing his mind. A recent editorial in Valor Econômico, Brazil’s leading business daily, recognized the benefits BRICS membership had produced for Brazil, but warned that the grouping was “ceasing to be a source of opportunities and becoming a source of risk” if it became a club of largely authoritarian regimes with anti-Western positions.”

Next year, it will be Brazil’s turn to host the BRICS Summit, forcing the Lula government to decide whether to invite Putin, against whom the International Criminal Court, of which Brazil is a member, has issued an arrest warrant—a situation which leaves little space for fence-sitting. The time when BRICS membership had only upsides and virtually no downsides for Brazil seems to have come to an end.