This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on the education crisis

Juan Gabriel Vásquez’s latest novel, Volver la vista atrás, begins innocuously enough: Sergio Cabrera, a Colombian filmmaker, is being honored in Barcelona with a retrospective of his career. He’s also having a family reunion. Seeing his wife and his two children for the first time in a while, he’s hoping for a second chance. Maybe, he thinks, his life could resume its normal course. Then, an unexpected phone call brings the news that his father has died.

Cabrera finds himself undergoing a more personal kind of retrospective, reckoning with his relationship with family and the influence of a radical left-wing father. The book’s title, which translates literally as “look back,” is borrowed from a poem, “Caminante,” by Spanish modernist Antonio Machado, which describes life as walking down a path whose steps we can never retrace.

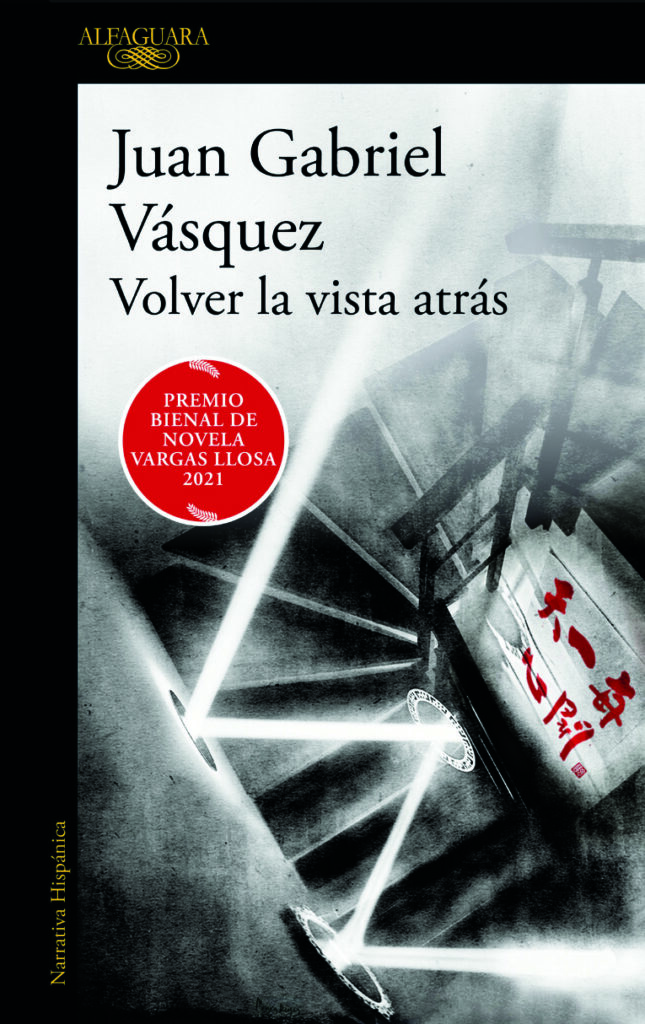

Volver la vista atrás

by Juan Gabriel Vásquez

Alfaguara

Paperback

416 pages

It’s this “look back” that provides the narrative structure of Vásquez’s phenomenal novel. Volver la vista atrás immerses the reader in the lives of three generations of Cabreras, real people whose stories Vásquez remakes into fiction. As the crushing weight of the 20th century’s political violence falls on their private, intimate lives, the paths they will never set foot on again remain indelible in their memories.

Threatened by Nationalist rebels under General Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War, Sergio Cabrera’s grandfather flees with his family to the Dominican Republic. But there, another ferocious dictatorship looms: that of the merciless Rafael Leonidas Trujillo. They flee again, spending brief periods on the Haitian border and ending up in Colombia in 1945. There, Sergio’s father Fausto hears for the first time about the Communist Party, the guerrillas of the Eastern Plains and the revolution that was about to kick-start 50 years of bloodshed.

Struggles between right and left in Colombia mirror the unstable political landscape of Spain before the Civil War. “You’re not old enough to remember,” Sergio’s uncle Felipe tells him, “But that’s how it was. That’s exactly how it was.” As Fausto commits himself to the life of a revolutionary, young Sergio and his sister Marianella are caught up in a swirl of communist fervor that takes the family to Maoist China.

Abandoned by his parents, who return to Colombia to join the struggle there, Sergio grows up amid the ferment of the Cultural Revolution. Forced to follow his father’s commands to prepare for the revolution, he joins the Red Army. At 19, finally returning to a Colombia racked by violent repression and far-left insurgency, Sergio becomes a guerrilla fighter in the Popular Liberation Army (EPL). In the jungle, he must survive punishing marches, hunger and disease before he can earn the chance to get away – and become the distinguished filmmaker he is at the book’s outset.

Vásquez’s novel is an indelible portrait of the extremes of conviction, a deep probe into the mysterious origins of the fanaticism to which we are all susceptible. Why write a novel about a real-life person, and not a biography? The author’s own words best describe his reasons for navigating the murky waters between fact and fiction. Upon receiving the Mario Vargas Llosa 2021 Biennial Novel Prize, Vásquez thanked Sergio and Marianella Cabrera, not only his subjects but his personal friends, “for the trust with which they placed in my hands their memories, their documents, their lives, so that I could reimagine them through the novel, (the form) we human beings have invented to narrate the world.”

—

Del Valle is a lawyer and writer based in Berlin