This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on transnational organized crime

A long time has passed since Christopher Columbus, Hernan Cortés and Francisco Pizarro arrived in the New World, and it seems like there is little that we don’t know about their historic voyages from Spain. They came, they saw, they conquered, killing hundreds of thousands of locals, plundering unimaginable amounts of gold, silver and jewels, and transforming the region in almost every possible way.

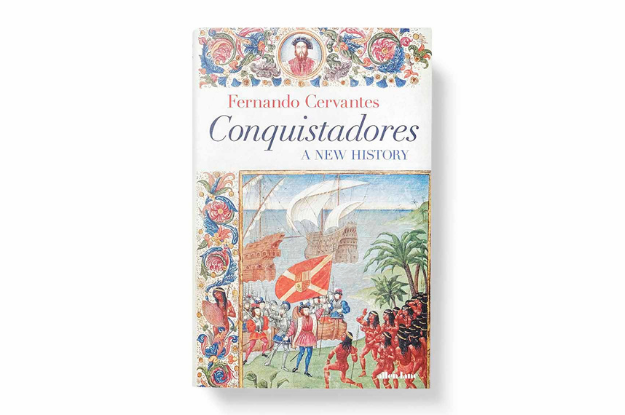

Conquistadores: A New History by Fernando Cervantes is billed as a “reframing” of the conquests and comes as the world vociferously reviews all kinds of long-standing narratives that were penned by the victors.

But this book by one of the world’s leading authorities on the intellectual and religious history of early modern Spain and Spanish America is not a revisionist history.

Cervantes has written about the atrocities meted out by the conquistadors for decades and his key argument here is that any discussion of the conquistadors’ actions must be set in the context of their own time, not in ours. The conquistadors were products of their environment, where great glory and riches came to those daring enough to hit the high seas and discover new worlds.

The Mexican historian explains the background to those voyages and his total command of the details is the key to the book’s success. The basics are well known: Columbus touching land in the Caribbean while searching for a westward route to Asia; Cortés striking out unauthorized for Mexico and seizing Tenochtitlán, then one of the biggest cities in the world; and Pizarro’s brutal domination of the Incas and the sacking of Peru.

Most of what we know about these conquests comes from the Spaniards’ own telling: Some of the details were written down after the fact and much else came in self-serving missives to the Spanish crown designed to impress the court and inflate the deeds and the loyalty of those reporting them. There is no comparable version of events from the side of the Mexica or Incas.

Cervantes judiciously lays out the narratives we do have and helps steer the reader toward the most likely version of events. He frequently questions the official versions and paints rounded pictures of the conquerors, the vanquished indigenous leaders, and the worlds they inhabited in the late 15th and early 16th centuries.

The book is excellent in describing the rich and sophisticated worlds they encountered. Cervantes’ description of Tenochtitlán and the battles to control it are vivid, and the portraits of Moctezuma, Atawallpa, and the power struggles that proceeded the fall of the Inca empire are equally fantastic.

Cusco, for example, was described to Spanish king Charles V as “the greatest and most splendid of all the cities ever seen in the Indies. … [S]o beautiful and graced with so many fine buildings that even in Spain it would certainly stand out.”

The booty taken from Peru was phenomenal: 26,000 pounds of silver and more than 13,000 pounds of 22.5 carat gold in the first four months alone.

“Exploring for its own sake was all very well, but what the monarchs really needed was cash,” Cervantes writes as he balances out the conquests’ religious, commercial and imperial motives.

The book is weighty — there are detailed descriptions of the Taíno people’s creation myths, the origins of the Spanish inquisition, and Bartolomé de las Casas’ powerful moral opposition to the conquests — but it is rarely slow or dull.

In fact, it reads like both an adventure story and a travelogue, with Cervantes an enthralling guide.

If there are quibbles, they are over the slightly uneven pace. There is a heavy accent on the early expeditions in the Caribbean and Mexico. Pizarro’s conquest of Peru is given less space and the pages devoted to Hernando de Soto’s fruitless traipse around the southern U.S. in search of gold are uneventful in comparison. There is little mention of the conquests of Colombia, Chile, Bolivia or Paraguay and nothing about the Portuguese conquest of Brazil, which is a shame, as a comparison would have made for interesting reading.

But those are minor grumbles. Conquistadores is a tour de force and should be welcomed by anyone interested in Latin American history.

__

Downie has lived and worked in Latin America for almost 30 years, reporting from more than a dozen countries. He is the author of Doctor Sócrates: Footballer, Philosopher, Legend, a biography of the Brazilian footballer and political activist. He currently divides his time between the U.K. and Brazil.