This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on food security in Latin America

In his memoirs, the iconic Mexican President Benito Juárez sums up his time living in exile in New Orleans in two terse sentences, primarily outlining the length of his stay (18 months). Accounts from contemporaries give us a few details: a job rolling cigars, meetings with other revolutionaries. But those months, from December 1853 to June 1855, are, for the most part, a lacuna in Juárez’s otherwise well-documented life. Into that lacuna steps Yuri Herrera, one of Mexico’s most venerated writers, with his new novel, Season of the Swamp.

Juárez’s rise from orphan child from a Zapotec family in Oaxaca, to law student, to progressive reformer politician is the stuff of Mexican national myth. It’s akin to the log-splitting origins of his contemporary, Abraham Lincoln—but Juárez has the added distinction of being Mexico’s first and, to this day, only Indigenous president. Herrera’s Juárez is far from a bootstrapping hero—instead, he’s an overwhelmed exile, in shock at his abrupt departure from the country he had been working to liberate from conservative usurpers.

This Juárez floats from scene to scene, not so much acting as being acted upon, by scammers, co-revolutionaries and policemen—an observer of the cruelties of life in an antebellum slave-trading city. He has almost no direct dialogue, only elliptically recounted conversations and silent musings. Time passes in fits and starts of dissociation.

Season of the Swamp

Yuri Herrera

Translated by Lisa Dillman

Graywolf Press

Hardcover

160 pages

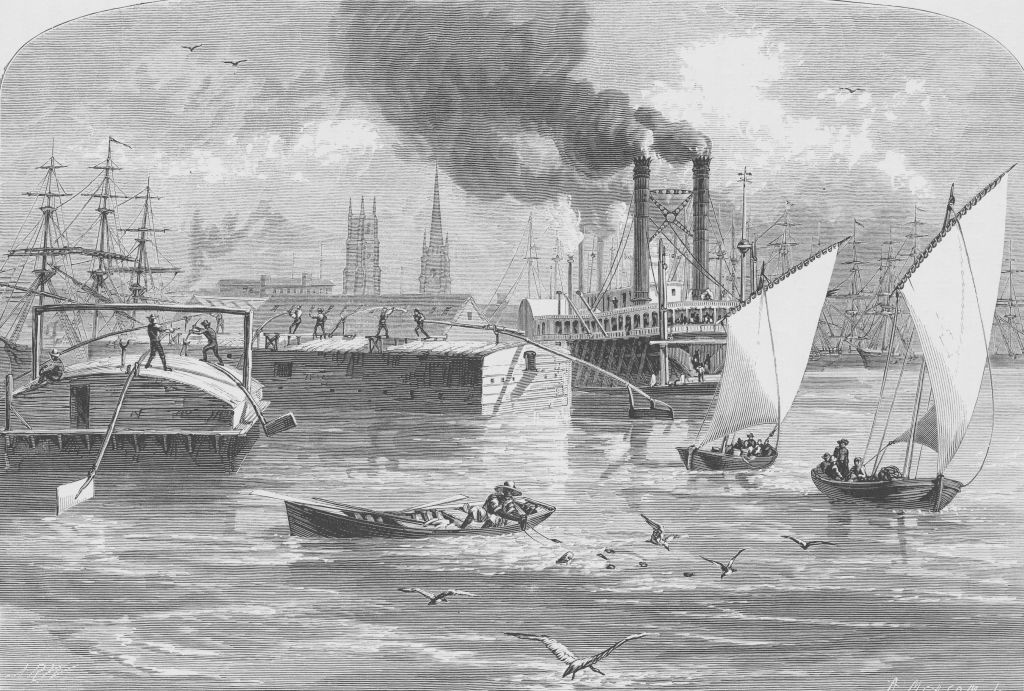

Early on, the narrator of the book sums up Juárez’s entire Louisiana sojourn as he passes through customs: “His reception on disembarking from the packet boat had been a foretaste of all that was to come: waiting and waiting and not knowing words and not being seen and learning the secret names of things.”

Twinned helplessness and shame dog Júarez. He is 47 years old, a former judge and governor, dazzlingly well-educated. He is also in exile, imprisoned and deported by longtime political rival Antonio López de Santa Anna to a country where he does not speak the language, relying on the financial support of his wife, watching the politics of his nation slide into conservatism, with no clear way forward, just meetings with fellow revolutionaries. The swamp in the title refers not only to the physical geography of New Orleans, but to the spiritual geographies of exile.

Like any good novel of spangled, chaotic New Orleans, Season of the Swamp is a picaresque, complete with bear fights and brothels and absinthe and arson. There’s a fever dream where Juárez’s friend and anticlerical reformer Melchor Ocampo kills a pair of French vampires, not with stakes to the heart but with workers’ nails, picked up from a railroad. Lisa Dillman, Herrera’s longstanding translator, transmits the playfulness of the original, complete with typographic flourishes and anachronistic slang, long a signature of their collaborations (and beautifully explicated in Dillman’s own essays on translating Herrera).

Beneath the absurdities, this is a novel of Benito Juárez’s political formation. The book is studded with racial violence—violence by police, by runaway-slave catchers, even by those simply trying to get by. Early on, Juárez also befriends Thisbee, a Black coffee shop owner who helps enslaved people find their way to freedom. Their conversations make up the emotional and moral center of the book. With her, Juárez can be himself, and Thisbee shares his outrage at injustice. But where Juárez is passive, Thisbee is all activity, using her home and coffee shop to help people escape enslavement. By the time Juárez is back on a boat home, to a country that has successfully deposed the tyrant that exiled him, his watching and waiting has transformed into a sense of purpose to help shepherd Mexico into a more just future.

—

Oliva is an essayist and embroiderer based in Chicago