This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Uruguay

The word “monster” can be traced back to the Latin verb monstrare, meaning “to show.” The monsters in our stories often illustrate something about our societies: For example, the story of Dracula became a hit just as the germ theory of disease began to catch on, explaining how a bite could be infectious. In their own dark way, the monsters and myths that populate Mariana Enríquez’s gloriously creepy masterpiece, Our Share of Night, illuminate the history and present of Enríquez’s native Argentina.

The novel centers around a father, Juan, and his son, Gaspar, who are on the run from a powerful occultist group, the Order. At a motel on their first night on the road, they’re confronted by what Juan calls an “echo”: the ghost of a woman, pregnant, drowned and despondent. Juan is used to seeing this kind of apparition, but Gaspar isn’t. As Juan teaches his son to dispel the ghost, he reflects on what it means in 1981 in Argentina to be visited by the dead: “It was always like that in a massacre, the effect like screams in a cave—they remained for a while until time put an end to them.”

Enríquez’s novel finds fruitful overlap between the horrors of the supernatural and the horrors of history. Take, for example, the Order that is in pursuit of Juan and Gaspar. It’s a multinational occultist organization that worships a shadowy, evil god, the Darkness—and in Argentina, it’s led by the Bradford family. Their ancestors arrived from Britain in the 1870s and made a fortune from land won during the Conquest of the Desert, a genocidal campaign against Argentina’s Indigenous people. From there, their wealth and power, both occult and political, was built on the backs of others: those who work in their mate plantations, the desaparecidos sacrificed in their occult rituals, and Juan himself, whose spiritual powers allow him alone to communicate with their god.

Father and son are now on the run. Juan’s wife, a Bradford herself, is dead, and the Order is looking for Gaspar to see if he shares his father’s gifts. We follow Gaspar from the age of six to his 20s, skipping forward and flashing back to his parents’ courtship in a novel as sprawling as it is tensely paced.

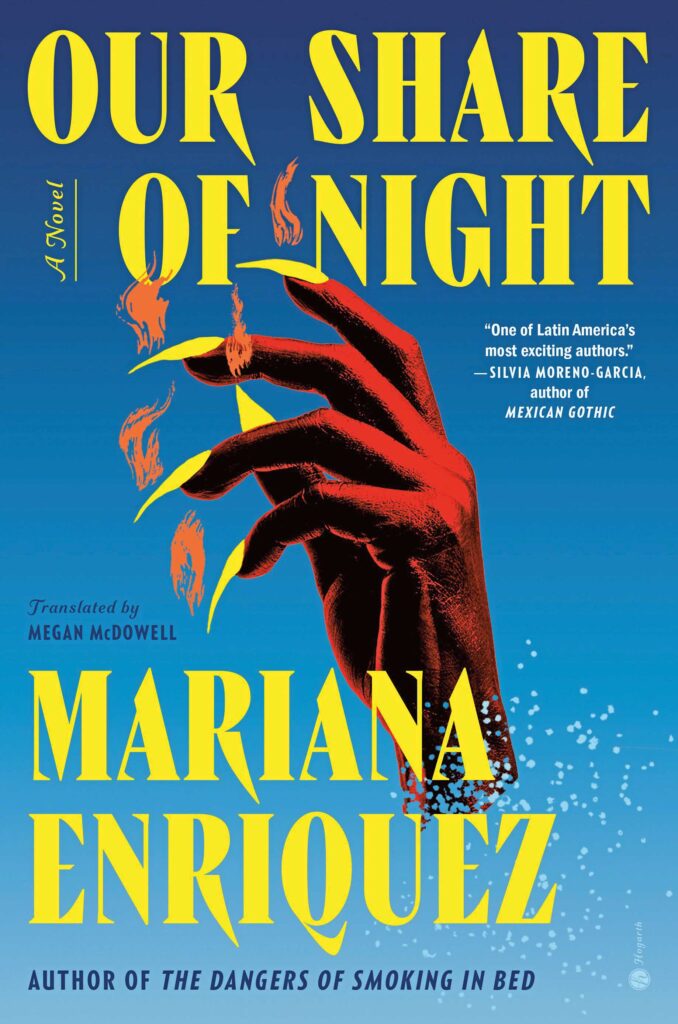

Our Share of the Night

by Mariana Enriquez

Translated by Megan McDowell

Hogarth

Hardcover

608 pages

Enríquez, working again with her longtime translator, Megan McDowell, uses Argentina’s history, full of tumult, gaps and mysteries, as the scaffolding for her dark and mysterious world. How else to think about the thousands of desaparecidos in Argentina’s history if not as sacrifices to a darkness that ate them whole? The book’s world grows from the sense that some evils are too large to come from simple human greed and ambition—but it in the end it undermines this notion.

The novel highlights, as much through real-world events as through magical ones, that power and evil often grow from the same root. The beauty and sadness of Enríquez’s book, however, comes from the relationship between father and son, which illustrates how the disempowered are often drawn into complicity and collaboration in order to survive. Juan hates his position as medium for the Bradfords but also recognizes that the medical care and privileges they grant him have kept him and his son alive.

Just as Dracula reflected our nascent understanding of germs, Enríquez’s monsters point at the problems of Argentina’s history and present. The Bradford family’s empire reflects how Argentina’s natural resources have benefited only a slim proportion of its population. The Bradfords use their financial wealth to protect and enhance their supernatural powers—just as the politically powerful in Argentina continue to widen the gap between rich and poor.

—

Oliva is an essayist and embroiderer. Her book, Rivermouth: A Chronicle of Language, Faith and Migration, is forthcoming from Astra House in June.