In Chile, three police officers have been killed in the line of duty in the space of one month. On March 12, Álex Salazar was run over by fleeing suspects. Two weeks later, suspected criminals shot and killed Rita Olivares Rayo. And on April 5, Daniel Palma was shot in the head during a traffic stop. Repeated tragedy has roiled the country’s politics, sparking public anger over rising crime—and many feel the government has not done enough.

Security issues have become a heavy burden for leftist president Gabriel Boric. Elected on a mandate to change Chile’s social and economic model, Boric has witnessed support for those changes largely evaporate as a constitutional reform process failed last September and crime has taken center stage. Now the government faces an adverse political environment that will test Boric’s ability to keep his fractious left-wing coalition together as he pivots towards a more tough-on-crime stance.

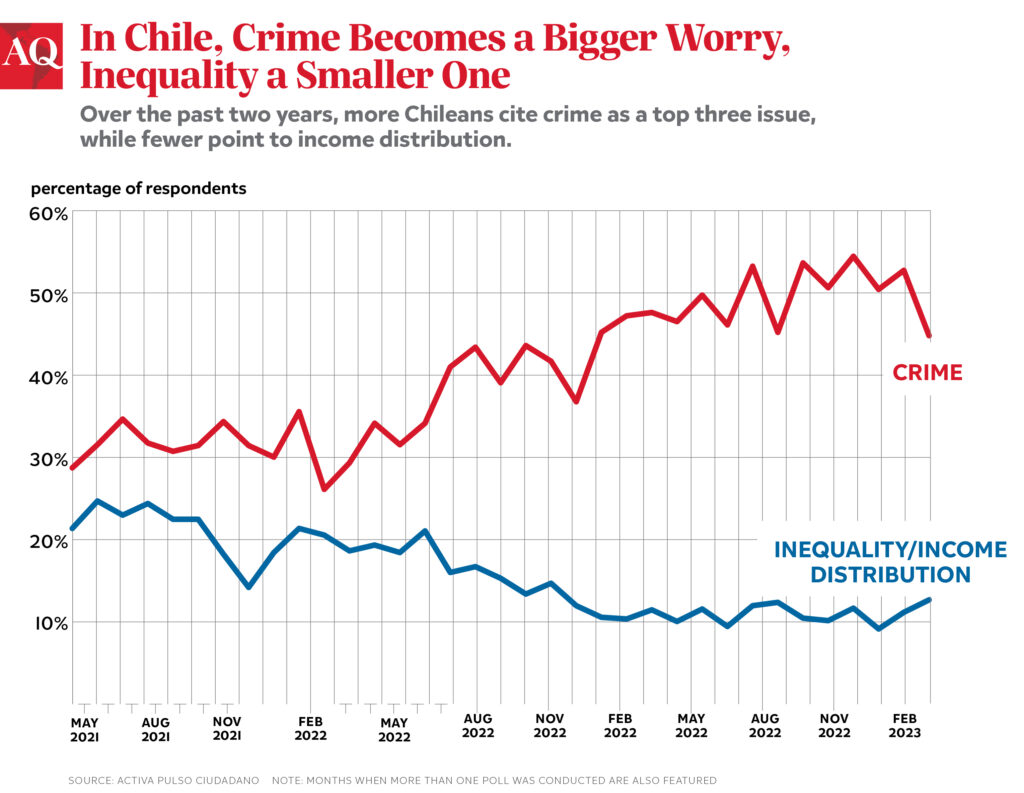

The steepness of the decline in Boric’s popularity is unprecedented in recent Chilean history and he has had one of the shortest honeymoons among recently elected Latin American presidents. The complicated security situation in Chile is an important reason for his falling approval—he must confront challenges such as ongoing violence in the Araucanía region by radical Mapuche groups and more crime in urban areas. Chile’s homicide rate increased by 32% year-over-year in 2022. In March. three-quarters of Chileans reported fearing becoming a victim of crime, according to local pollster Cadem.

Causes for the rise in crime include human trafficking, drug trafficking as well as theft of natural resources. Chile’s relative affluence makes it a tempting target for transnational crime syndicates, especially as a destination for migrants and narcotics. But criminals are also becoming more brazen—as last month’s police murders attest—forcing Boric to adapt quickly.

A steep learning curve

Chileans see crime as the most pressing issue facing the country. At the end of March, 71% said that crime should be the focus of the government’s policy efforts, up from 60% earlier in the month. Voters give the Boric administration poor marks on crime, with 69% saying that they disapprove of the government’s handling of crime and only 29% approving (mirroring Boric’s approval and disapproval ratings).

One reason for the poor public evaluation is Boric decision at the end of 2022 to pardon 13 convicted criminals, a decision that polls showed was rejected by the majority of Chileans and soured relations with the opposition, leading to the collapse of negotiations over new security laws. The move was seen as a concession to his left-wing base, which has been on the losing end of policy battles since the rejection of the proposed constitution in September.

After March’s police murders, the government has taken action expediting the passage of six laws that seek to expand police powers. Five of the six laws received broad legislative support, but the so-called Naín-Retamal law failed to get the support of Boric’s own party, Apruebo Dignidad. The law expands the scope of legitimate self-defense for police officers, but members of Boric’s party opposed the law, fearing it would enable excessive use of force by police. Nevertheless, the government supported the law and Boric announced that he would increase spending on security by $1.5 billion this year.

More tough choices lie ahead

Crime is likely to remain the most important issue facing the Boric administration as the underlying causes of rising crime will take concerted efforts to address and may take years to see concrete results. The opposition is also likely to keep a laser-like focus on crime as it is the government’s political weak spot.

The government’s chief critic is the popular mayor of Providencia, Evelyn Matthei, who is the frontrunner to be the presidential candidate for the right-of-center Chile Vamos coalition. She has focused on security issues as a main plank of her campaign and has criticized the government for not taking crime seriously enough, saying that they need to appoint a crime czar.

But there’s a risk Matthei’s tough-on-crime rhetoric may be insufficient to speak to voters frustrated with what they see as rampant insecurity. The success of Nayib Bukele in El Salvador to rapidly reduce homicides has proven to be an attractive model for political figures throughout the continent and Chile may not be an exception. Figures such as the far-right José Antonio Kast or right-wing populist Franco Parisi may leverage widespread angst about crime to propose more radical anti-crime policies. Bukele-style policies are unlikely to be rolled out in Chile owing to the country’s strong democratic institutions, but risks to due process rights could be high nonetheless.

In the meantime, Boric will have his hands full as he continues his move to the political center, introducing security policies that bolster the powers and resources of Chile’s police. Prior to becoming president, Boric opposed many of the reforms that would have empowered the security forces, but as president he has been forced to compromise.

Boric is adapting to the new reality around security in Chile. But his left-wing base, both congressional and popular, will likely remain hostile to his new policies. It may decide to abandon him, which could turn his administration into a lame duck—and torpedo the left’s electoral chances in 2024.

—

Saldías is a Latin America and Caribbean Analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit and received his PhD in Political Science from the University of Toronto.