Two candidates, Sergio Massa and Javier Milei, now chase Argentina’s presidency. While the contentious runoff on November 19 rivets most citizens, a crucial question hangs over the upcoming vote: Would either of them be able to solve the country’s worst crisis in more than two decades? While there’s no easy answer, a painful adjustment is unavoidable.

The last man standing will inherit a dystopian economy undermined by runaway inflation, a deepening recession, widespread poverty and failing fiscal and monetary policies. To make things worse, the central bank has almost no international reserves, while investors domestically and overseas are fed up with the story of a country oversold too many times in the recent past. The tale of hope no longer convinces, and in a challenging business environment, times call for action. And Argentina must act fast indeed once the election is sorted out.

To begin with, neither would have a majority in the legislature—especially not Milei. Massa’s Peronist coalition, Unión por la Patria, will have 34 of 72 seats in the Senate, with Milei’s libertarian party controlling eight. The Peronists will have 108 of 257 seats in the House, and Milei’s libertarians will hold 37. History shows that presidents without strong congressional support have tended to fare poorly in Latin America—many never even make it to their term’s end.

Complicating matters further, the most influential legislators from Massa’s party are from the leftist group, La Cámpora, led by Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and her son Máximo, a congressman. That will likely make it difficult for the centrist Massa to obtain his party’s support, let alone build broader coalitions, to pass the significant economic reforms that dire circumstances warrant.

Should Milei win the presidency, he would have to gain the support of lawmakers from the parties that did not make it to the runoff, mainly from Patricia Bullrich’s Juntos por el Cambio. That would make it difficult, if not unlikely, to pass any of his radical reforms, such as shutting down the central bank or dollarizing the economy.

Macroeconomic pain

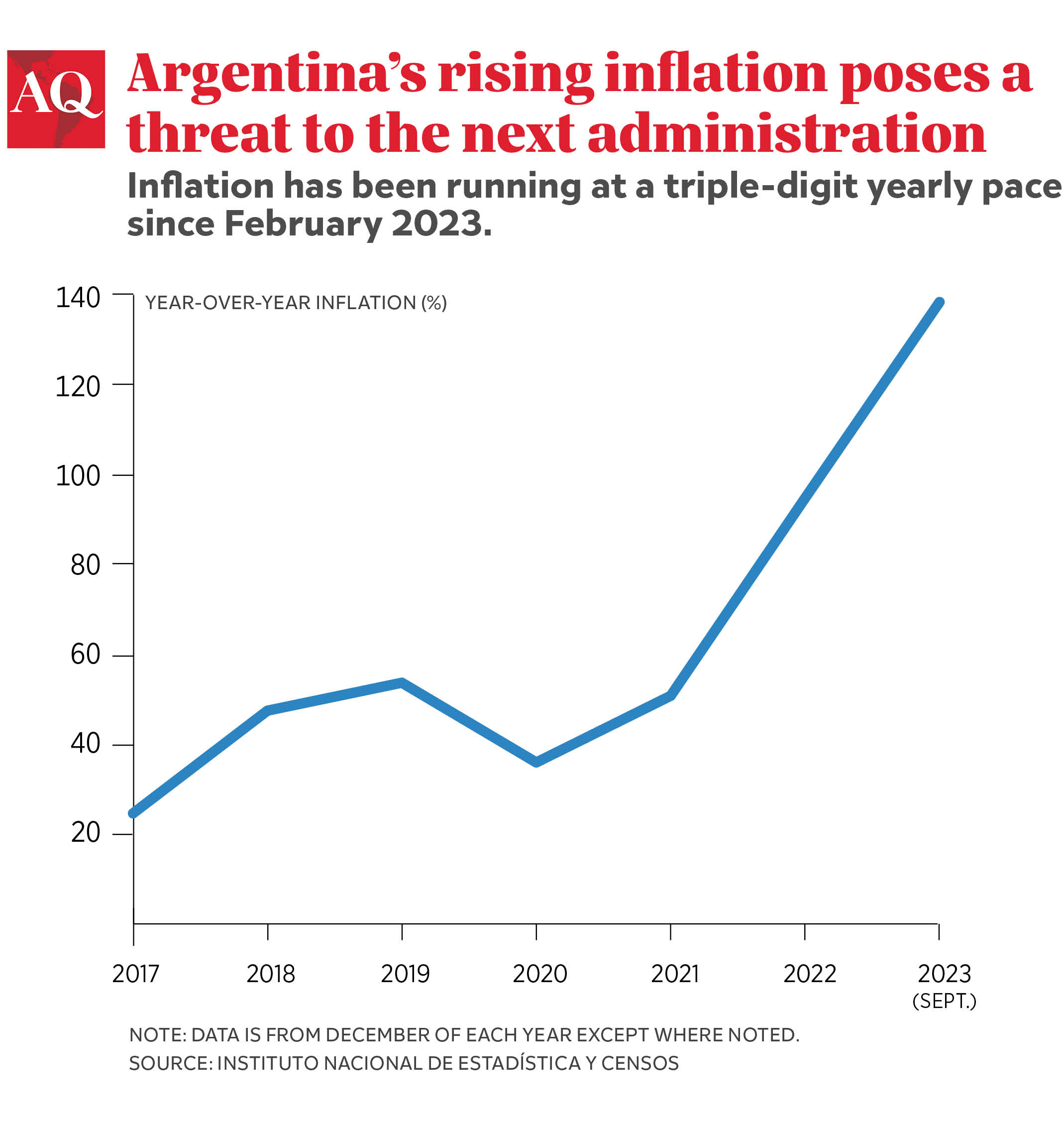

Inflation will likely keep running at a triple-digit yearly pace, as it has been since February. In August and September, annualized monthly inflation accelerated to beyond 300%, by far the fastest rate in over three decades. In simple terms, Argentina could slide into hyperinflation at any moment—an existential threat to the incoming government.

Bad as they are, the inflation statistics do not capture the underlying, potentially explosive economic pressures. Heavy-handed government interventions have kept prices of food and energy, benchmark interest rates, and the official exchange rate substantially below market-clearing levels.

The economy is distorted by massive subsidies to consumers of fuel, electricity, natural gas, water and mass transit; heavy taxes and periodic caps applied to food exports like soybeans and beef; longstanding controls on supermarket prices; and rationed access to foreign currencies at a multiplicity of exchange rates.

Chances are that unpopular but necessary corrective measures will be needed soon, likely pushing inflation higher still in the short term. It is estimated that energy prices would have to be doubled overnight and adjusted in line with inflation after that, for them to reattain their pre-pandemic levels.

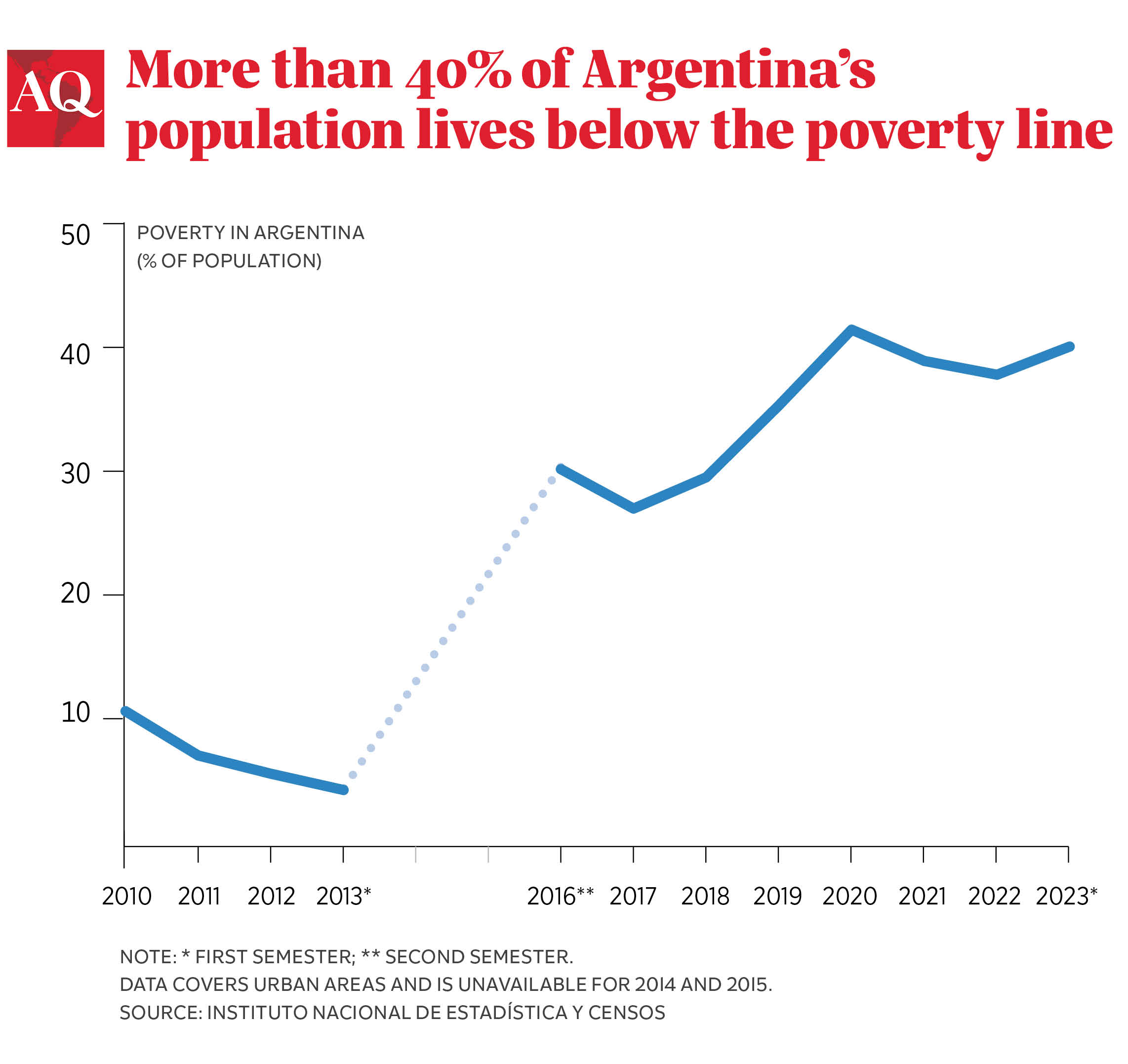

Economic activity as measured by real gross domestic product will shrink by an estimated 3% this year, with per capita income likely to fall to nearly 15 percent below the level in 2011, the prior peak. The result: more than 40% of the population lives below the poverty line. That number was less than 7% more than a decade ago. At least half the population depends on benefits from government-funded supplemental income and job programs, and it is estimated that 6 out of every 10 Argentine children under the age of 18 live in households classified as poor. Absent these welfare programs, the extent of poverty would be greater still.

While the unemployment rate has remained relatively low and stable at around 7%, the job market has suffered over the past decade. Vacancies are primarily available in small, unproductive firms that operate “off the books”; thus, they offer neither employee benefits nor make employment-related contributions to pensions.

It is estimated that, since the end of 2016, three out of every four job openings filled have landed applicants into mostly low-paid positions in Argentina’s large underground economy. Without the growth of informal, non-compliant work arrangements, the unemployment and poverty rates would be much higher.

A weakened central bank

Argentina’s accelerating and increasingly disruptive inflation has been fueled by fiscal deficits primarily financed by borrowing from the country’s central bank, the BCRA, given the absence of better alternatives.

The fiscal roots of high inflation were planted in early 2020 when the newly inaugurated government of President Alberto Fernández hiked public spending and ran a substantial budgetary deficit—the equivalent of almost 9% of GDP—to protect vulnerable households and firms from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Unfortunately, that fiscal largesse took place while the government defaulted on its obligations to domestic and international investors, which meant that the authorities had little choice but to fund the outsized deficit primarily with loans from the BCRA.

While Argentina’s fiscal deficits have since averaged a more modest 4% annually of GDP during 2021-23, the government’s failure to repair relations with and instill renewed confidence among institutional investors and lenders has cemented a damaging dependence on continuous BCRA inflationary financing.

The central bank has tried hard to minimize its harmful impact by aggressively selling bills (LELIQs), thereby mopping up many unwanted, newly printed pesos the government has spent. Yet after four years of funding the government via interest-free loans while placing with the banking system a colossal amount of LELIQs paying skyrocketing interest rates, the BCRA has rightly spawned concerns that it might drive itself into insolvency and/or that it could default on the LELIQs—triggering a systemic financial crisis.

A related and more pressing problem is that the BCRA is not only overstretched in terms of LELIQ liabilities, but it is also woefully short of international—mostly U.S. dollar—reserve assets. Said foreign-currency reserves have fallen from $41 billion at the start of the year to around $25 billion. Once various short-term BCRA liabilities are netted out, the largest of which is money owed to the People’s Bank of China, reserves drop to near zero.

But here, too, the paltry foreign currency reserves in the BCRA’s vault do not tell the whole story. The authorities have significantly tightened importers’ access to dollars by requiring them to rely on short-term borrowing from their suppliers and subsidiaries abroad. As a result, instead of the BCRA’s foreign-currency reserves dropping an extra $16 billion between the start of 2022 and mid-2023, Argentine importers’ short-term indebtedness has ballooned by that amount—with prospects for repayment in doubt.

Restrictions imposed on the repatriation of profits and dividends by foreign-owned companies operating in Argentina have worked in the same manner: they have spared the BCRA upwards of $10 billion in losses of foreign-currency reserves—but at the expense of keeping the earnings of foreign investors trapped.

While miracles happen, and regardless of whether Massa or Milei triumphs at the polls, the odds are stacked against either of them being able to deliver on the campaign promises they are making.