In recent weeks, Argentina’s government and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) announced a preliminary agreement for a new program – the 23rd in the country’s long history with the multilateral lender. Unfortunately, the details provided so far are underwhelming, with policy commitments and reforms nowhere near what Argentina needs to improve its economic prospects, suggesting the country may remain stuck in its loop of low growth and instability.

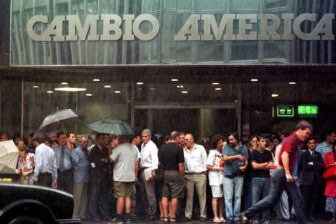

Following the IMF announcement, and a restructuring of its debt with private sector creditors in August 2020, Argentina will have addressed the dire external debt service situation it faced at the end of 2019. However, the economy has continued to deteriorate. Inflation remains at around 50%, the fourth-highest in the world behind Venezuela, Zimbabwe and Sudan. GDP per capita is significantly below the level observed in 2010, sovereign debt prices signal another default may be expected, and the country is running out of international reserves even during a year in which soy prices – its main export – are significantly above their historical average. It is clear that Argentina’s society has struggled for decades to establish a political consensus on the role of the state, how to distribute income and wealth and how to set a tax system that efficiently funds government’s activities to accomplish these goals.

Argentina’s latest crossroads came after the government struggled to make a $700 million payment to the IMF due in late January, a legacy from its previous 2018 deal with the lender (I retired in 2021 as the Fund’s director for the Western Hemisphere). The Extended Fund Facility (EFF) program now in the works will allow Argentina to refinance that payment to the Fund while the program remains on track as Argentina completes the quarterly reviews. In principle, through this mechanism, the IMF provides long-term (longer than the traditional standby facility) financial support to address the member country’s balance of payments pressures while it implements the deep structural changes needed to address the shortcomings of the economy. The question is whether the program supports a feasible long-term strategy that would provide a clear shot of exiting decades of stagnation and instability.

Central to explaining Argentina’s equilibrium of low growth and financial instability is the size of the state. Public expenditure is above 40% of GDP, one of the highest levels in the Americas, with a negligible investment component and there is no social agreement on how to fund it. Furthermore, Argentina’s access to foreign savings is seriously compromised which has resulted in a very low investment rate. Argentina needs to reduce public expenditures to increase public and domestic savings, which would in turn allow for an increase in investment. In addition, the inconsistency between an ambitious welfare state and the lack of a social agreement on how to finance it, has led to macroeconomic instability, a variety of controls that hinder private sector activity, and a lack of predictability of regulatory policy. Together these elements conform a lethal economic status quo of chronic instability and negative income per capita growth.

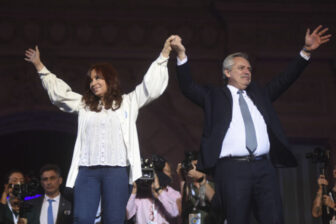

But the announced program does little to address these problems. The macroeconomic policy targets of the program are very weak, there is negligible strengthening of macroeconomic institutions, and a structural reform agenda is completely absent. In short, the current program implicitly accepts that solving Argentina’s socioeconomic puzzle is impossible, and settles for the minimum conditions to avoid descending into the abyss. The program clearly reflects President Alberto Fernández´s view that high indebtedness is at the center of Argentina’s problems – and not the most accepted view among mainstream economists, that debt and inflation are actually the symptoms of much deeper structural issues in the country. The program is also the product of a president who prefers blaming past administrations and commenting on the pitfalls of capitalism, rather than doing the job for which he was elected – undertaking necessary policies to set Argentina on the course of stable and inclusive growth. The IMF faced a complex situation in deciding which course of action to take. It is evident that Argentina was not in a position to service its debt with the Fund in the next few years, and that the current political equilibrium does not allow for a broad political agreement that lays the foundation for a healthy recovery.

In deciding what route to take, the Fund must have assessed the impact of each option on Argentina’s society and on the reputation and credibility of the IMF. Although letting Argentina fall into arrears might have been tempting in terms of consistently applying the Fund’s policies, it would have contributed to significantly worse outcomes for Argentine society. The unpalatable alternative was accepting a program that significantly reduces the probability of a financial explosion in the short run, but will not contribute to putting the country on course to exit decades of instability and stagnation. This option has important costs as the probability of the program going off-track is high, and it will generate moral hazard as other countries will demand similar treatment in their engagements with the multilateral. However, trying to influence policymaking in Argentina with an IMF program and providing financial support so that Argentina remains current on their financial obligations will reduce the probability of significantly worse outcomes for the country in the next two years and will support a better economic outcome for Argentina’s society. Regardless of the direction chosen, the IMF would continue to be a hostage of Argentina’s unresolved distributional conflicts and political polarization.

It seems that, in the end, the IMF decided not to become the odious collector that punishes Argentina for not being able to repay their debt, nor the ogre that imposes tough medicine. By agreeing to this very weak EFF under the logic of the achieving the “possible program” and not the “right program” the IMF is putting its reputation on the line behind the authorities’ economic agenda while it waits for the 24th program with Argentina. The least they should expect is for President Fernández to own the program, to implement it impeccably and to clearly explain to the population of Argentina why this is the best course of action to avoid yet another full-blown financial crisis.