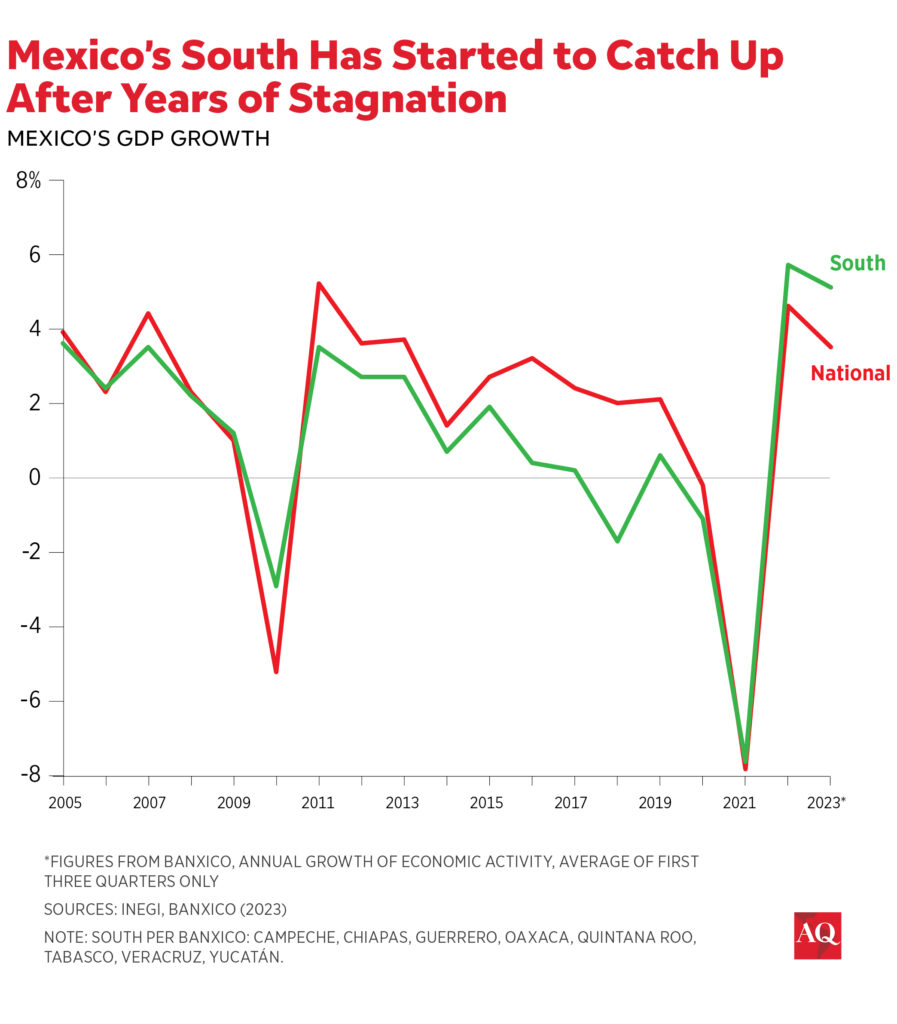

On the back of rising public investment, two southern states put up the best growth numbers in Mexico last year, signaling what may be a historic shift: The country’s south is expanding faster than the north.

This shouldn’t be a surprise; the much smaller southern economies have more room to grow. Yet the fact has grabbed national headlines because the south had been mired in remarkably stubborn stagnation for decades.

Leading the scoreboard, the state of Oaxaca averaged more than 10% year-over-year growth through the first three quarters of last year. Over the same period, the south averaged 4.9%, far outpacing the north (2.7%) and the country as a whole (3.47%), according to Banxico, Mexico’s central bank. If this trend holds when official 2023 data is released, it will mark the third consecutive year that Mexico’s north has been outpaced by the south, which Banxico defines as Campeche, Chiapas, Guerrero, Oaxaca, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, Veracruz and Yucatán.

But Oaxaca’s rapid rise and the new prominence of the south are due almost entirely to massive federally-funded infrastructure projects. “This is not sustainable,” said Sofía Ramírez Aguilar, the director of México, ¿cómo vamos?, a Mexico City-based think tank monitoring socio-economic development. These investments will pay off only if the new infrastructure leads to strong private investment in other sectors, like manufacturing and logistics, she told AQ.

Even though this hasn’t happened yet, the ruling Morena party seems committed to pushing big bets on infrastructure, even after President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO)—who is from the southern state of Tabasco and has made investment there a key priority—leaves office in September.

Oaxaca shows this strategy’s potential and limits, as well as its staying power within Morena’s ranks. The state’s gaudy growth numbers are based on the Tehuantepec Interoceanic Corridor—an overland shipping route from Oaxaca to Veracruz intended to compete with the Panama Canal—which is under construction and projected to cost around $3 billion. Oaxaca is also benefiting from a port overhaul, a major new highway, and a $3 billion coking plant at the Salina Cruz refinery by Petróleos Mexicanos, the state-owned oil company, among other government investments.

Its neighbors are receiving similar largesse; the Dos Bocas refinery in Tabasco is slated to cost over $16 billion, and the Maya Train stretching 1,500 kilometers across five southern states will cost over $28 billion.

AMLO’s administration is counting all this as a victory. “Thanks to the efforts undertaken in favor of the development of the southern states, economic growth in these states is twice as high as the average observed under the two previous administrations,” Mexico’s Finance Minister Rogelio Ramírez de la O said before the Senate in late September.

Uncertain bets

The private investment necessary to support sustainable growth hasn’t yet materialized, so it’s still possible the federal projects will become “white elephants,” said Karla González, associate director of sovereign and international public finance at S&P Global Ratings, using an expression that has become common in Mexico for infrastructure projects that turn out more costly than beneficial. AMLO’s presidency has seen several premature inaugurations of significant projects that “are functional, but not super complete,” she said. Mexico City’s controversial Felipe Ángeles airport, inaugurated in 2022, fits this description.

Even so, “Oaxaca seems headed in the right direction,” Ramírez Aguilar said. The poverty rate in the state—over 58.4% in 2022, compared to 36.3% country-wide—is falling modestly, as it is across the south. Unemployment is also falling, and incomes are rising due to AMLO’s minimum wage increases and the infrastructure construction boom tightening the labor market.

AMLO and his acolytes—including Oaxaca’s Governor Salomón Jara—credit this partly to cuts to unwieldy social programs in favor of expanded cash transfers, which 14 million families nationwide now receive. This is generating locally-driven private investment in the south. According to a December report from Mexico’s central bank, more low-income families have greater spending power, so construction firms, for example, have invested more in building low-income housing.

To build on this progress, at least six “special development zones” along the Tehuantepec Corridor route are being built in the state, each of which aims to attract a different industry. They still lack a formal tax framework and will need private sector partners willing to offer training to overcome the severe shortage of skilled labor in the region, said González of S&P. Despite these shortcomings, a Danish investment firm inked a memorandum of understanding to develop a $10 billion green hydrogen project in Oaxaca, precisely the type of investment the Corridor seeks to attract.

An enduring agenda

Governor Jara seems eager to maintain AMLO’s policies—and style—after the president’s term ends in September. In Jara’s first year in office, he visited over 370 municipalities, attempting the kind of peripatetic calendar that AMLO used to raise his profile and portray himself as close to the people. Jara, like AMLO, also says he has cracked down on corruption and emphasizes that his administration is keeping spending tight. “We received a government in ruins, very indebted, full of phantom employees, and deeply affected by corruption,” he said in a November speech marking the first year of his term.

Oaxaca’s relatively conservative public financing has earned the state a boost in its economic outlook and creditworthiness over the past few years, said Matthew Walter, a Moody’s analyst based in Mexico City. Moody’s Local México currently gives the state an A-.mx stable rating, noting its liquidity and decreasing debt.

In December, AMLO traveled to Oaxaca to promote the state’s success. He gave a speech from Salina Cruz, a port that the Corridor seeks to connect to Coatzacoalcos, in Veracruz. Jara had the first seat behind him. AMLO told the audience that his administration doubled the federal government’s public spending, from 500 billion pesos to over 1 trillion—a key pillar of his “Fourth Transformation” agenda.

“I’m confident that Oaxaca will continue the same policies,” AMLO said, “that will grow thanks to all the projects … They’ll get bigger and others that are needed will get done,” he said.

Moody’s estimates that a whopping 89% of Oaxaca’s operational revenue comes from the federal government, but this spigot likely won’t be turned off any time soon. Morena’s presidential candidate and the frontrunner in the 2024 race, Claudia Sheinbaum, has Gerardo Esquivel on her team, “one of the major proponents of infrastructure investment as a motor for growth,” Ramírez Aguilar said. “He has a very clear vision of investing in logistics infrastructure in a way that has cross-cutting benefits across industries.”

Morena seems poised to continue to push more of the same big bets. And even if Sheinbaum loses the presidential race, the Tehuantepec Corridor is promising enough that it will “very likely continue regardless of who is in charge,” González said.