This week, Latin American presidents gathered in Mexico for the inauguration of Claudia Sheinbaum. All those present hailed from the ideological left, including Cuba’s dictator and the democratically elected leaders of Guatemala, Colombia, Brazil, Chile and Honduras. On the same day, 4,500 miles away in Buenos Aires, Nayib Bukele and Javier Milei, the two celebrity leaders of the Latin American right, were standing on the balcony of the Casa Rosada waving to a crowd below.

These were two separate gatherings, happening in what might have been two separate worlds, at a time when Latin America’s left and right are for the most part not speaking to each other. When they do, it’s often on Elon Musk’s X – where just in 2024 we have seen presidents call each other “terrorists,” “communists,” “fascists” and “war criminals.”

The problem is more than just rhetoric. If we look at the biggest challenges facing Latin America, and indeed the world, almost all of them require collective action. Whether it’s organized crime, or climate change, or the need for more infrastructure, trade and economic growth, these are challenges that no one country can solve alone or in ideologically “pure” bubbles. And while it’s true that polarization is a big problem in the United States and throughout the West, it’s a particular diplomatic challenge in today’s Latin America: Argentina has difficult relations with Brazil and Colombia, Mexico shuns Peru and Ecuador… the list goes on.

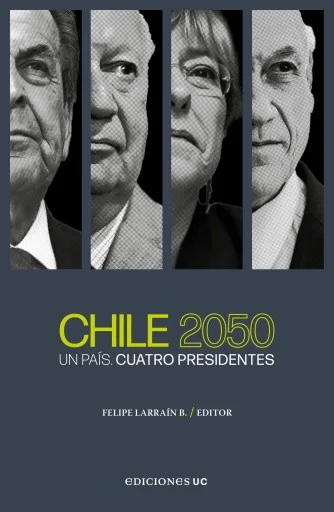

In that context, a new book published in Chile is like an oasis in the desert. The book brought together four Chilean former presidents from across the ideological spectrum: Eduardo Frei (1994-2000), Ricardo Lagos (2000-06), Michelle Bachelet (2006-10 and 2014-18), and Sebastián Piñera (2010-14 and 2018-22), who completed his contribution before his untimely death in February. The goal was to brainstorm long-term policy solutions for the next three decades, hence the title: Chile 2050: Un país. Cuatro presidentes.

The book is, in some ways, an attempt to reset the public debate and perhaps turn back the clock a bit following Chile’s mass protest movement of 2019, which set off a period of uncertainty – and these days, considerable pessimism about the country’s prospects. Long accustomed to being Latin America’s A-student, with its highest economic growth rates but also some of its best social indicators, Chile has struggled in recent years with a slow economy and a scary surge in organized crime. In the book, the presidents offer a variety of tried and true recipes, such as private-public partnerships to build infrastructure, as well as newer initiatives to seize on Chile’s still unrealized potential in green hydrogen and lithium.

Ediciones Universidad Católica & Clapes UC, Editor: Felipe Larraín B.

But the real value of the book is that it happened at all. Such a project would be unthinkable today in Brazil, Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, the U.S…. maybe everywhere in the region but Uruguay. What made Chile different? Among other factors, the careful preservation of those little norms and customs that make a republic: Bachelet and Piñera, the country’s first conservative president following the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, over the years held good-natured conversations in which they recognized their differences but also the other’s good faith and patriotism. Several of these chats were broadcast on television with an obvious civic objective. Chile may also be an example of the general rule that countries with the most recent experience in losing their democracy tend to value it the most.

That said, the book poses a challenge: How to keep the momentum going and ensure that it is more than a mere artifact of the culture of the 1990s and 2000s, like a greatest hits album by Shakira or La Ley. This actually seems less of a risk for Chile itself; President Gabriel Boric, age 38, clearly maintains the same republican spirit as his much older predecessors. But for the rest of us, the question lingers: How to build, or rebuild, a politics where left and right can speak to each other – both within and among countries?

Here, too, the book has value. We have seen time and again that, to overcome polarization and populism, it’s not enough to lecture voters that democracy is at risk. In today’s world that sounds fake, like politics as usual. The book focuses instead on real-life policies, on trade and taxes, recognizing that only through economic growth, social progress and overall well-being will citizens resist the siren call of more divisive, authoritarian leaders.

“Democracy must deliver,” Bachelet told a crowd in Washington on Wednesday at an event to launch the book at the Inter-American Development Bank. Frei and Piñera’s widow, Cecilia Morel, also spoke, as did Felipe Larraín, Piñera’s former finance minister who was instrumental in putting the whole endeavor together. (I also had the privilege of saying a few words.) There was spirited disagreement but no insults – and no cursing. In the Washington of October 2024, it was an oasis indeed.