This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on A (Relatively) Bullish Case for Latin America

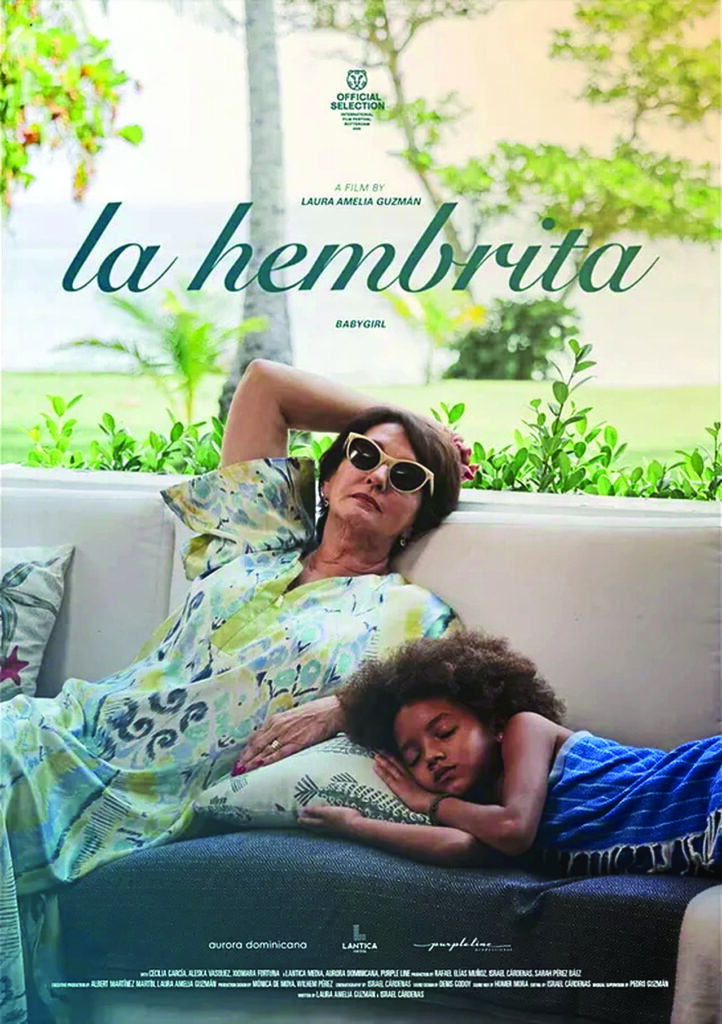

A skinny black girl sits in a bathtub, while a snobby-looking white woman—bejeweled, with red nails and makeup fresh out of the salon—washes her coiled hair. The girl seems happy and at ease, and so does her older companion.

This unlikely pair animates Laura Amelia Guzmán’s first feature film, Babygirl (originally titled La hembrita), a sophisticated and subtle study of class and race tensions in the Dominican Republic. In the film, Guzmán avoids the temptation to indict her characters. Instead, she constructs a narrative that strongly favors ambiguity, showing just how interconnected are the worlds of rich and poor, black and white.

Contrasts still abound in Babygirl. Dominique, a middle-aged socialite, longingly awaits the birth of her first grandchild to a son who lives abroad. As she prepares for her trip to Canada, her longtime live-in maid, Carmen, begins to look after her own granddaughter, Yanet. A few days later, under circumstances never fully explained, Carmen disappears, leaving her granddaughter behind.

Babygirl

(La Hembrita)

Directed by Laura Amelia Guzmán

Screenplay by Israel Cárdenas and

Laura Amelia Guzmán

Distributed by Aurora Dominicana

and Lantica Media

Starring Cecilia García,

Aleska Vásquez and

Xiomara Fortuna

Dominican Republic

What follows is the development of a tender, if at times compromised, bond. Dominique tends to Yanet as though she were part of her family. She indulges her with shopping, takes her swimming, even casually calls her her granddaughter in front of strangers. These displays of affection mirror earlier ones that took place between Dominique’s two sons and Carmen. A series of asides reveals Carmen essentially raised these boys and feels they are, to some degree, hers too. When the sons call their mom, they always ask to speak with Carmen too.

Such an arrangement is no anomaly in Latin America and the Caribbean. Up to 18 million people are believed to be employed as domestic workers in the region. The vast majority, 93%, are women. Many are of African descent and most are informally hired. Last year, the Dominican government took steps to protect these workers’ rights with a minimum wage, insurance and pensions. As poverty declines and the middle classes expand, more initiatives of this kind are sure to arise.

Yet in Guzmán’s Babygirl, there is a cruel asymmetry between the matriarch and her servant: Dominique knows so little about Carmen’s life, she can’t restore Yanet to her family. (“I don’t know where they live. I have no leads, I’m on my own,” she explains to a friend.) But Carmen is intimately acquainted with Dominique’s social life, her every idiosyncrasy. So why is Dominique so eager to take responsibility for Yanet?

Guzmán has said she sought to navigate the “emotional-moral conflicts that arise when class divides give way to matters of conscience and responsibility.” Dominique is a woman beholden to the money-earning men in her life, namely her husband and two sons. Throughout Babygirl, we see her ignoring radio and TV announcements possibly implicating her family in corruption. In the face of her own powerlessness, Yanet seems to allow Dominique to shoulder accountability.

In this sense, Babygirl embodies a longstanding Latin American dynamic. Nearly 200 years ago, a 41-year-old Simón Bolívar wrote a letter to his sister, asking her to treat the enslaved Afro-Venezuelan woman who had raised him “as though she were my mother.” Babygirl belongs to a lineage of contemporary films, including Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma and Lucrecia Martel’s middle-class dramas, that wrestle with these social relations unabashedly.

Despite its disparity, the relationship between Dominique and Yanet bears genuine love—and requires sacrifice from Dominique, in the form of rebukes from family and friends. But she continues to benefit from the wealth of her husband and sons, regardless of its possibly questionable origin. Even if Yanet were to absolve Dominique of her class sins, they would both still be left in a profoundly unequal country, full of precarity for the many and prosperity for the few.

—

Alvarado is a writer and former assistant editor at The Atlantic