SÃO PAULO—Though their ideologies are a world apart, U.S. President Donald Trump and Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva will now be forced to interact, as the respective leaders of the two largest economies in the Western Hemisphere. And even though Trump and Lula have very different stances on geopolitics and much else, pragmatism could push both to find ways to make the bilateral relationship at least functional, though likely with significant tensions and limitations.

Undoubtedly, the global ambitions of the expanding BRICS bloc of countries, China’s growing influence in Latin America, the approaches to the multilateral institutions and climate change will be central in defining the rapport between the two leaders. And Trump and Lula have mostly different vantage points on these matters. Lula sees himself as an eminent voice in the Global South and a beacon of multipolarity, while Trump covets a world where the U.S. plays the ultimate leading role.

As Lula has been adamant about expanding BRICS, its bank and global financial reach, Trump has warned against plans to de-dollarize the world. “The idea that the BRICS Countries are trying to move away from the Dollar while we stand by and watch is OVER,” Trump posted on X, weeks after winning the November election. He immediately added that “there is no chance that the BRICS will replace the U.S. Dollar in International Trade, and any Country that tries should wave goodbye to America.”

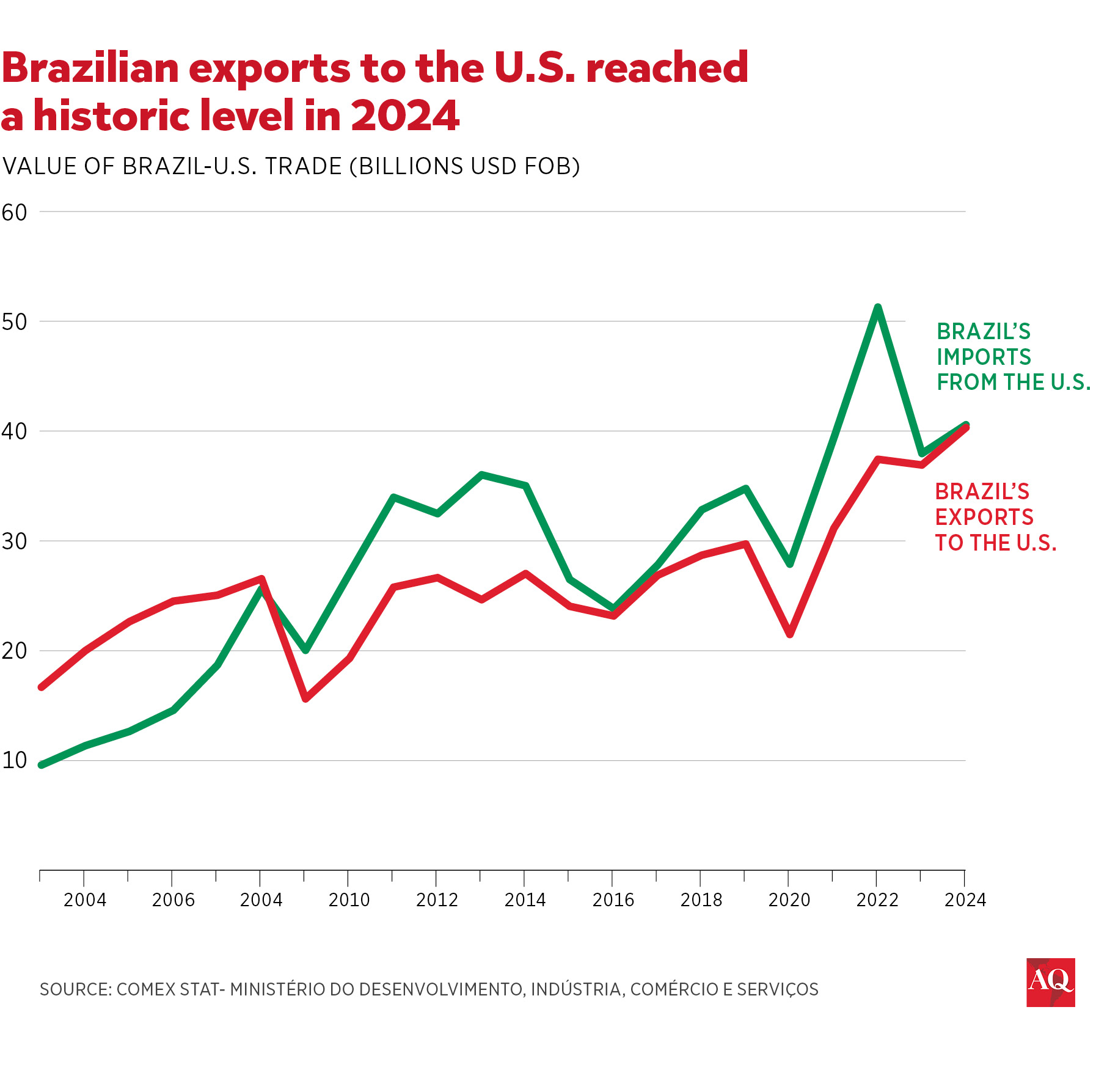

But Trump and Lula may align on favoring a quicker negotiated end to the war in Ukraine. And in any case it is facts that will most likely guide the relations between the two countries in this new era. The U.S. is Brazil’s second biggest trading partner after China, and their ties have grown steadily. Just last year, Brazil’s exports to the U.S. exceeded $40 billion, a historic level.

No wonder Lula has avoided confrontation so far. While he didn’t call Trump personally to congratulate him on his victory, Lula used social media to set the tone of their expected relationship. “The world needs dialogue and joint work to have more peace, development, and prosperity. I wish the new government luck and success.”

But the prominent role of Elon Musk, a frequent critic of Brazil’s Supreme Court and Lula’s PT party, in the new Trump administration has drawn worries in Brazilian policy circles. With Trump back at the helm, the U.S.-Brazil relationship must find new convergence points—a difficult but feasible task.

Challenges

Brazilian diplomats identify several potential sources of tension in bilateral relations: geopolitical frictions, trade disputes, the complex dynamics between Trumpism and Bolsonarismo, and the big tech billionaires’ growing influence in the U.S. government.

Brazil’s ties to certain non-Western countries could be a flash point. In 2025, Brazil will preside over the BRICS group and will host the bloc’s summit. Meanwhile, the country’s relationship with China has been deepening, including a state visit from President Xi in 2024 during the G20, and the signing of several agreements between the two countries. This is a partnership that increasingly involves technology and areas of competition with the U.S.

In the commercial sphere, Trump’s protectionist measures could particularly impact Brazil’s agricultural and energy sectors, further eroding the multilateral trading system. Given Trump’s tendency to use tariffs as both economic and political leverage, combined with Brazil’s limited access to his inner circle, Brazilian officials expect significant challenges in negotiating favorable terms. Also, as Ricardo Zuniga, American diplomat and partner at Dinámica Americas, notes, Trump’s aggressive tariff policies can potentially damp global growth and spur inflation. This economic pressure could be particularly challenging for Brazil as it approaches its 2026 elections, potentially undermining Lula’s efforts to revitalize the economy.

The future of bilateral cooperation in other key areas remains uncertain. There’s cautious optimism on labor rights thanks to Trump’s surprising nomination of Lori Chavez-DeRemer, who has a union-linked background. But climate cooperation and defense partnerships face particularly grim prospects, with Brazilian diplomats especially concerned about how Trump’s climate denial stance might impact COP 30, scheduled to take place in Belém, Brazil, this year.

These concerns are amplified by the emerging composition of Trump’s diplomatic team. Marco Rubio, the new Secretary of State, is a seasoned observer of Latin American affairs and has criticized the PT government, specifically targeting Brazil’s deepening ties with China and the Brazilian Supreme Court’s handling of social media regulation, particularly Justice Alexandre de Moraes’s decision to temporarily suspend X in Brazil, which Rubio characterized as a concerning restriction on freedom of expression under Lula’s administration.

Bright spots

Nonetheless, there are opportunities for dialogue. Zuniga states that Brazil is a potential source of critical minerals and rare earths. Production is currently dominated by China, which is prepared to restrict its use as a form of pressure against the U.S. or in response to American export controls. Brazil’s industrial capacity makes the country a potential partner for other strategic supply chains, such as pharmaceuticals.

From an energy cooperation perspective, the U.S. should maintain its “all of the above” strategy, which focuses on fossil fuels while remaining open to alternative energy sources – this would enable dialogue with Brazil. According to Brazil Institute Director Bruna Santos, Brazil-U.S. cooperation on sustainable energy is already institutionally established, particularly in green hydrogen development.

On the war in Ukraine, both the Lula and Trump administrations are expected to support a diplomatic solution based on current battlefield conditions, favoring immediate negotiations over continued military escalation. This approach aligns with their shared preference for a swift resolution, even if it means Ukraine might need to negotiate from its present position rather than waiting to strengthen its military advantage. This convergence in diplomatic outlook could be further reinforced under the new administration, as suggested by Rubio’s recent vote against additional military aid to Ukraine.

In terms of regional policy, the Brazilian government believes that to contain China, the United States needs a positive agenda of investments and commercial openness. In this regard, Mauricio Claver-Carone, Trump’s envoy to the region and former IDB president, published an article in AQ in July 2024 advocating for a “prosperity diplomacy” as a policy for the Americas.

The pressing question is whether this perspective of strategic rapprochement and dialogue will prevail in bilateral relations. The uncertainty stems from the fact that within the Trump administration, there are groups with divergent views on how to approach Latin America, both from a general standpoint and in more sensitive cases such as the relationship with Venezuela, one tending more toward collaboration and the other, more heavy-handed demands.

In general, Trump’s foreign policy for his second term promises to be marked by the same transactional approach that characterized his first administration, always seeking to maximize return on American investment in its international relations, but now with more force, with teams that are guided by loyalty to the president. And the main component of Trump’s management of international relations will continue to be unpredictability, which makes it particularly challenging to anticipate the direction of relations with Brazil from 2025 onwards.

—

Magnotta is a Global Fellow at the Wilson Center Brazil Institute, a Senior Fellow at the Brazilian Center for International Relations and a professor of the International Relations Program at Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado in São Paulo.