Ricardo Monreal likes to talk about the constituyente permanente, the legislative power to rewrite Mexico’s constitution. It’s a power that his Morena party is currently making full use of—and Monreal is at the head of the charge.

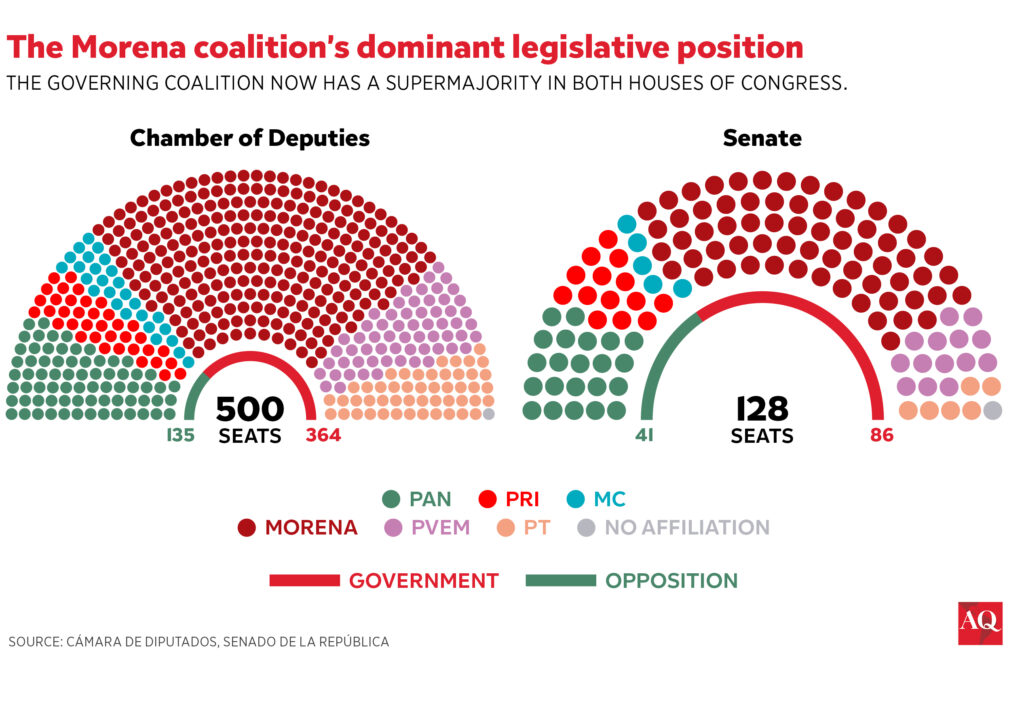

As leader of the Morena-led coalition in the country’s lower house, which has a dominant supermajority, Monreal is pushing through sweeping reforms that are shaking Mexico’s political system to its foundations. The lower house’s approval of a law on November 20 dissolving seven watchdog public bodies (it now goes to the Senate) is just one part of an agenda that includes revolutionizing the country’s judicial system and overhauling its energy regulatory system, among other changes.

“We’re reaffirming the supremacy … of the constituyente permanente,” Monreal, 64, said to the press last month as he proposed changes that would insulate Morena’s reforms from judicial challenges. “The population gave us this supermajority, and we’re going to use it—responsibly.”

The outline of the current reform agenda comes not from current President Claudia Sheinbaum but rather from her predecessor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), who set out a list of 20 reforms in February. It seemed like a wish list at the time, but since the June 2 elections brought Morena large majorities in both houses of Congress, it’s turned into a checklist that Morena has made clear it will complete.

Along with the president and his opposite number in the Senate, Adán Augusto López, Monreal is the public face of that legislative agenda, which he is shepherding through the lower house. The silver-tongued Zacatecan, who also teaches at UNAM, Mexico’s most prestigious university, seems to enjoy the spotlight, speaking fluently and extemporaneously to journalists and fellow legislators alike.

Throughout his long political career, which has included countless ups and downs, Monreal has proved himself a survivor again and again—including recently, when he offered a public apology after it emerged that he’d used a helicopter to get to Congress. President Sheinbaum singled him out for criticism in one of her daily news conferences. Using an expensive form of transportation seemed to clash with Morena’s embrace of austere economizing by public officials.

On social media, Monreal brushed off the criticism, posting a picture of himself climbing on a motorbike. “In emergencies, it’s important to be punctual,” he wrote, offering an oblique explanation for using the helicopter. “Today, things called for a motorcycle.”

Mexico’s current political situation offers Monreal an opportunity for quick redemption from this public tongue-lashing. On November 15, President Sheinbaum sent to Congress a $460 billion budget proposal for 2025 to rein in public spending with sizable cuts in defense, security, health, education, and environmental areas. Monreal’s job is to help get it approved without major hiccups by the end of the year. Following the controversy surrounding the proposed reductions, he said the budget would need a “major surgery.”

There’s little doubt he’ll succeed. Under Monreal’s watch, Morena’s reforms have marched relentlessly through Congress, casting aside criticism from opposition politicians and concern from investors and onlookers abroad. In the face of criticism from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the government coalition has shored up a major overhaul of the judiciary. The coalition is also considering folding Mexico’s autonomous state organizations into other government departments, overhauling energy policy, and other subjects.

From Zacatecas to Mexico City

Monreal is from the state of Zacatecas, where he first entered politics in the 1970s with the once mighty Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI). After turning left and joining forces with AMLO, a leading figure in the left-wing PRD at the time, Monreal won the Zacatecas governorship in 1998, launching his career. Politicians and analysts, whether friendly to Monreal or otherwise, frequently testify to his rhetorical abilities and raw political skill.

“He became one of López Obrador’s most important political operators,” said Mexico City-based political analyst Carlos Bravo. “He’s a todo terreno, [he is] a territorial operator as well as a parliamentary operator, and he’s very, very tough.”

Monreal has long had his eyes on the role of Mexico City mayor, often a launching pad for Mexico’s presidency—but it has proved elusive. He lost a bid to become Morena’s candidate for the mayorship to Claudia Sheinbaum in 2018 and subsequently came in a distant fourth in Morena’s internal poll to decide the 2024 presidential nominee (Sheinbaum came in first).

Monreal’s current role in the lower house is a consolation prize for losing that internal contest—but many think he still has his sights set on a bigger role, and that he still thinks the road runs through Mexico’s capital.

Over the past several years, Monreal has remained active in Mexico City’s hard-fought municipal politics and has been involved in one way or another in several municipal-level contests that have seen internal divisions within Morena spark unexpected alliances with opposition forces.

There has long been speculation that Monreal threw operational support behind opposition politician Sandra Cuevas for the borough mayorship in Mexico City’s central Cuauhtémoc district in 2021—a post that Monreal himself held from 2015-17—in a bid to spike the presidential chances of rival Claudia Sheinbaum. The 2021 municipal elections, in which Morena lost ground in the capital, its stronghold, were indeed a blow to Sheinbaum’s ambitions—but she weathered it successfully.

Other forces within Morena seem to have returned the favor against Monreal this year, backing an opposition candidate who defeated Monreal’s daughter, Caty Monreal, in her race for the same Cuauhtémoc mayorship. For some analysts, that saga sums up Monreal’s somewhat troublesome place at the heart of Morena’s leadership.

“Some factions of [Monreal’s] political party joined the opposition [in Cuauhtémoc],” said Brenda Estefan, a professor at IPADE Business School in Mexico City and a columnist at Reforma. “He’s seen within Morena as a mal necesario. They need to have him but a lot of them are not on good terms with him.”

Even Monreal’s relationship with AMLO seems to have passed through rocky phases, with the then-president at one point suspending their regular meetings while Monreal was head of the Morena delegation in the Senate. The fact that Monreal is still around—and was given such a powerful position in the lower house—testifies to his political resilience.

Monreal in San Lázaro

Monreal’s current position has several advantages. His power to hand out coveted legislative positions lends him significant influence among lawmakers within the Morena coalition. It doesn’t come with major risks, allowing him to bide time, perhaps contemplating another future bid for the Mexico City mayorship—and doesn’t require the kind of aggressive vote-gathering tactics that Monreal’s counterpart, Adán Augusto López, has had to employ in the Senate. It associates him closely with the reform program—which, though controversial abroad, appears popular among Mexicans.

A final perk of the job for Monreal may be knowing that he’s creating headaches for his old rival, Claudia Sheinbaum, by pushing forward Morena’s legislative program. In Congress, Monreal doesn’t have to deal with the international fallout of the reform agenda, but Sheinbaum must. Her own distinctive political agenda seems so far partially overshadowed by the effort to carry out and defend her predecessor’s program.

“He’s a very [large] thorn in Claudia’s side,” said Bravo.