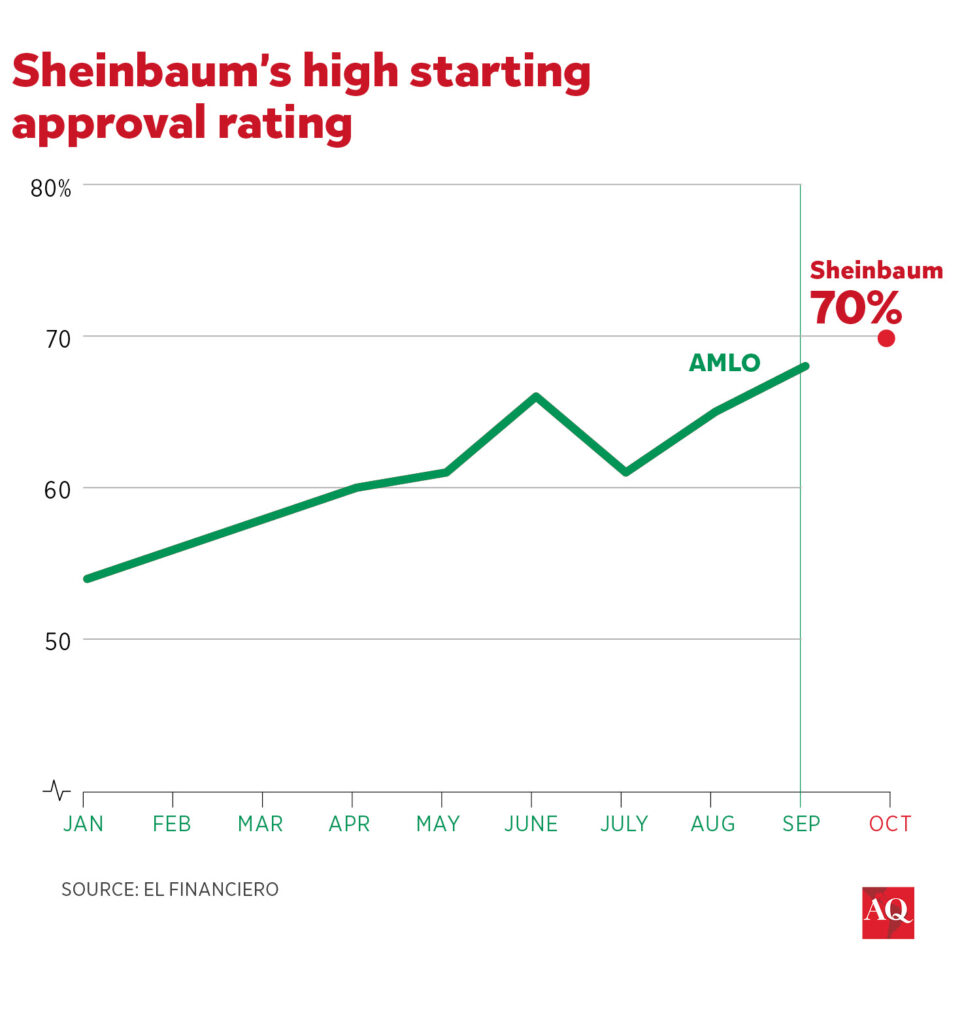

It’s been a month since Claudia Sheinbaum made history, becoming Mexico’s first female president in a landslide victory, after she promised to deliver “continuity with change” in comparison to her predecessor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

So far, we’ve seen far more continuity than change—although the full contours of Sheinbaum’s administration are still coming into view. Sheinbaum seems committed to proceeding with the transformation of Mexico’s political system that AMLO began. She has preserved AMLO’s anti-pluralistic rhetoric and his penchant for handing more power to the military. And it’s not clear how much emphasis her own signature policies—on the environment, for example—will receive.

Opposition parties, political analysts, the business sector, U.S. policy makers, and even some groups within Morena hoped that Claudia Sheinbaum would water down some of the constitutional reforms that AMLO proposed in February—especially the overhaul of the country’s judicial system, making all federal judgeships into elective positions. Those hopes have evaporated.

Instead, Sheinbaum has doubled down on the judicial reform, supporting a bill proposed by Morena lawmakers that states that constitutional amendments cannot be challenged in courts, and questioning the authority of the Supreme Court judges to evaluate the reform’s constitutionality.

A long to-do list

And it doesn’t seem like Sheinbaum will stop there. She has promised that she’ll make sure all of the 18 proposed constitutional amendments will be passed by Congress. Some have already been approved, like the judicial reform or a move to formalize AMLO’s decision to place the National Guard, a policing body he created, under the authority of the military. Others, such as the dissolution of autonomous government bodies, will likely be approved in the upcoming months.

The judicial reform gives the (currently Morena-dominated) executive and legislative branches two-thirds of the say over candidates for judicial positions, meaning the coalition has power to impose candidates that will align with their interests.

Add to the mix the ongoing bid to dissolve Mexico’s autonomous institutions, and you get a transformation of Mexico’s political regime. The reform to dissolve autonomous bodies would mean that the National Institute for Transparency, which is currently independent, would come under the control of the executive branch, while the National Electoral Institute’s independence and powers would be significantly reduced. The final wording of this bill will have to be studied carefully, but it appears that Mexico will have a more opaque government, with less accountability, and greater capacity to intervene in elections.

Another line of continuity is Sheinbaum’s attitude towards political opposition and criticism. In her rhetoric—as in AMLO’s—opposition parties are not the legitimate representatives of a considerable portion of the electorate; instead, they represent the interests of a malicious minority that aims to stop progressive change through illegitimate means. Similarly, analysts and journalists with critical stances are targeted in Sheinbaum’s mañaneras (the morning press conferences she inherited from AMLO), labelled as members of the “oligarchic” opposition.

This strategy encourages political polarization—and has proved quite successful in electoral terms. Under AMLO, it helped Morena strengthen its internal cohesion and maintain a mobilized and energized electoral base. No one should be surprised that President Sheinbaum is preserving it.

But with a Morena-led supermajority in both houses of Congress and the self-congratulatory tone that both the president and lawmakers exhibit when they announce any new reform, a significant risk emerges. If the ruling coalition keeps ignoring valid critiques, then it becomes hard for them to correct mistakes, detect weaknesses in their policies, and include alternative perspectives in their decision-making processes.

Rhetoric and the military

The rhetoric on human rights is another important continuity between AMLO and Sheinbaum: They portray human rights as an obstacle for political change, used in the past by elites to push neoliberal policies, and instrumentalized in the present by foreign-influenced organizations to stop allegedly progressive policies, such as the building of the Maya Train or the judicial reform.

That rhetoric, added to growing militarization, is dangerous in a country as violent as Mexico. President Sheinbaum has shown several signs that she will not only continue, but perhaps even intensify, AMLO’s militaristic policies. Just two days after taking the oath as president, Sheinbaum made a speech before the Army, calling Mexico’s armed forces “humanist, visionary and exemplary.”

Sheinbaum is making clear in public appearances that the armed forces will be a central piece in her government. She has confirmed that she will keep using the army for a wide range of tasks, including construction and administration of infrastructure projects. Meanwhile, the toll for human rights of this militarization has already begun to add up. Just a day after starting her government, the Army fired on a van carrying migrants, killing six of them and wounding others.

The Sheinbaum administration has ratcheted up the level of force used by the military against criminal groups—for example, in the Army’s killing of 19 suspected members of the Sinaloa Cartel on October 23. Sheinbaum and her security secretary, Omar García Harfuch, have committed to improving the use of intelligence and coordination between civil and military authorities to launch “strategic strikes” against the most violent criminal groups. They even sent a bill to Congress to reinforce these points. And García Harfuch has announced that the Mexican state will deploy specific regional strategies to contain violence in the most problematic states, such as Chiapas, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Michoacán, and Sinaloa.

The result of these policies is yet to be seen, but there’s a remarkable resemblance to the much-criticized security strategy of President Felipe Calderón (2006-2012), a major proponent of the War on Drugs.

There are crucial issues on which Sheinbaum’s agenda differs from AMLO’s—like her environmental projects, extending school hours in the public education system, a more structured and realist vision for the public health system, or the creation of “regional development poles.” But it’s not yet clear how much of emphasis these will have in Sheinbaum’s government, especially with her first few months devoted to enacting the complicated judicial reform and dealing with the violence crisis.

AMLO’s leadership was so strong, and his shadow is so large, that any changes Sheinbaum makes will likely be gradual, discreet, and quiet. It would be unrealistic to expect her to make a sharp break from a political figure as charismatic and popular as AMLO—even more so considering that both of them come from the same political movement and share the same causes. But judging by her first month in office, hers will be a government of significantly more continuity than change. For human rights, representative democracy, and a plural and open public sphere, this is not necessarily good news.