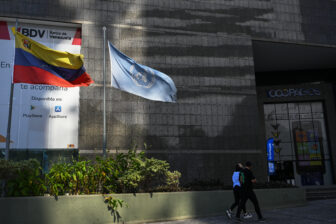

BOGOTÁ — Venezuela returned to the spotlight of global diplomacy as officials descended on New York this week for the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). Just days before, a UN fact-finding mission denounced Nicolás Maduro’s dictatorship for unprecedented repression and crimes against humanity in the wake of the July 28 election.

Many Latin American heads of state aggressively denounced the hegemonic regime ruling from Caracas in their UNGA addresses, while others took a far more conciliatory approach. Their sharply divided takes are just the latest evidence that Venezuela’s political crisis is set to become a powerful flashpoint in the region’s upcoming cycle of elections, exacerbating the intense polarization straining democratic systems throughout the hemisphere.

In his UNGA speech, Chile’s Gabriel Boric renewed his unequivocal denunciation of election fraud and human rights violations in Venezuela, calling the regime a “dictatorship that is trying to steal an election, that persecutes its opponents and is indifferent to the exile not of thousands, but of millions of its citizens.” And just after a federal court in Argentina ordered the arrest of Maduro and his Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello for alleged crimes against humanity committed against dissidents, President Javier Milei characterized Maduro’s government as a “bloody dictatorship.”

Guatemala’s President Bernardo Arévalo rejected Venezuela’s effort to “repress the aspirations of freedoms and justice” expressed through its elections, and the Dominican Republic’s Luis Abinader reaffirmed his call for Maduro to release a complete vote count. Speaking on Wednesday, Abinader added that “without the due transparency that any electoral process requires and without any documentary support, the crisis will only worsen.”

However, Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva didn’t mention Venezuela or his role as mediator in the current crisis in his speech, but on the sidelines of the UN event met with the French President Emmanuel Macron to review Venezuela’s situation. Colombia’s Gustavo Petro seemed to praise the country in a critique of global inequality, saying, “this richest 1% of humanity, the powerful global oligarchy, is who permits … economic blockades against rebellious countries that don’t fit within their control, like Cuba or like Venezuela.” However, in an interview with CNN, Petro urged to find a “political solution” to the ongoing crisis, while Maduro eyes formal inauguration on January 10.

While divisions over Venezuela are not new—Chavismo has been a lightning rod for political controversy since its emergence in the 1990s—the impasse over the July 28 election will likely make the debate increasingly contentious. And beyond rhetoric, Venezuela’s political crisis will create very concrete policy challenges for regional leaders.

Containing spillovers

Migration is the most immediate spillover effect of Maduro’s brutal wave of repression. The number of Venezuelans living abroad, already estimated at nearly 8 million, is likely to increase in the coming months as more people flee persecution. Governments throughout Latin America and the Caribbean are eager to avoid the social, humanitarian and political implications of a new wave of Venezuelan migrants—but they may not be able to.

Venezuela’s crisis will also likely empower organized armed groups as Maduro looks to shift the burden of repression from the armed forces to non-state actors such as the colectivos (pro-government gangs) and the National Liberation Army (ELN), a Colombian guerrilla group with longstanding ties to Chavismo. In the rest of the region, countries receiving Venezuelan migrants will face growing security risks linked to migration as gangs take advantage of migrant routes to enter new markets. These factors will only intensify anti-migration rhetoric in politics, as well as mano dura proposals to deal with it.

Meanwhile, international isolation—and an escalation of sanctions— will likely drive Maduro into a tighter embrace with China, Russia and Iran. In the past few months, Venezuela has taken steps to shore up ties with these governments to blunt the impact of a potential re-escalation of U.S. sanctions. For the U.S. and its allies, this scenario means not only the redirection of oil flows to geopolitical rivals but also growing Chinese and Russian military and intelligence influence in the Western Hemisphere.

These considerations all create incentives for the U.S., Brazil and Colombia to be pragmatic. These leading regional actors will aim to avoid a complete economic collapse and restrain the government’s repression, two factors that would contribute to a surge in emigration. This helps explain why the Biden administration has taken a cautious approach to new sanctions, as well as Lula and Petro’s strategy in their speeches before the UN. Brasília and Bogotá will prioritize maintaining relations with the Maduro government in hopes of securing cooperation on migration and security going forward.

A coordinated regional response

Divisions among countries have so far hobbled any regional response to Venezuela’s crisis. However, there is still time to correct course. The UNGA provides an opportunity for the region to speak with one voice, while also laying out a coherent and pragmatic strategy to deal with the regional spillover effects of the crisis.

This could constrain Maduro’s worst instincts, protect the opposition and its leaders, and help to mitigate repression, a key driver of migration. To do so, governments could make a joint declaration that establishes the illegitimacy of Maduro’s victory, document the numerous irregularities and violations of Venezuelan law, and reject the Supreme Tribunal of Justice’s decision to whitewash the election fraud.

Regardless of how the crisis evolves, regional cooperation will be essential to defending human rights within and outside Venezuela, as well as responding to migration challenges by attending to both migrants and receiving communities. Governments have a significant opportunity to take practical measures to facilitate information sharing, interoperability of systems for documenting migrants, and law enforcement coordination.

No external actor can bring about a democratic transition in Venezuela. But the region can still take steps to defend democracy—albeit symbolically and with a long-term view—while also working to mitigate both external and internal spillover effects.