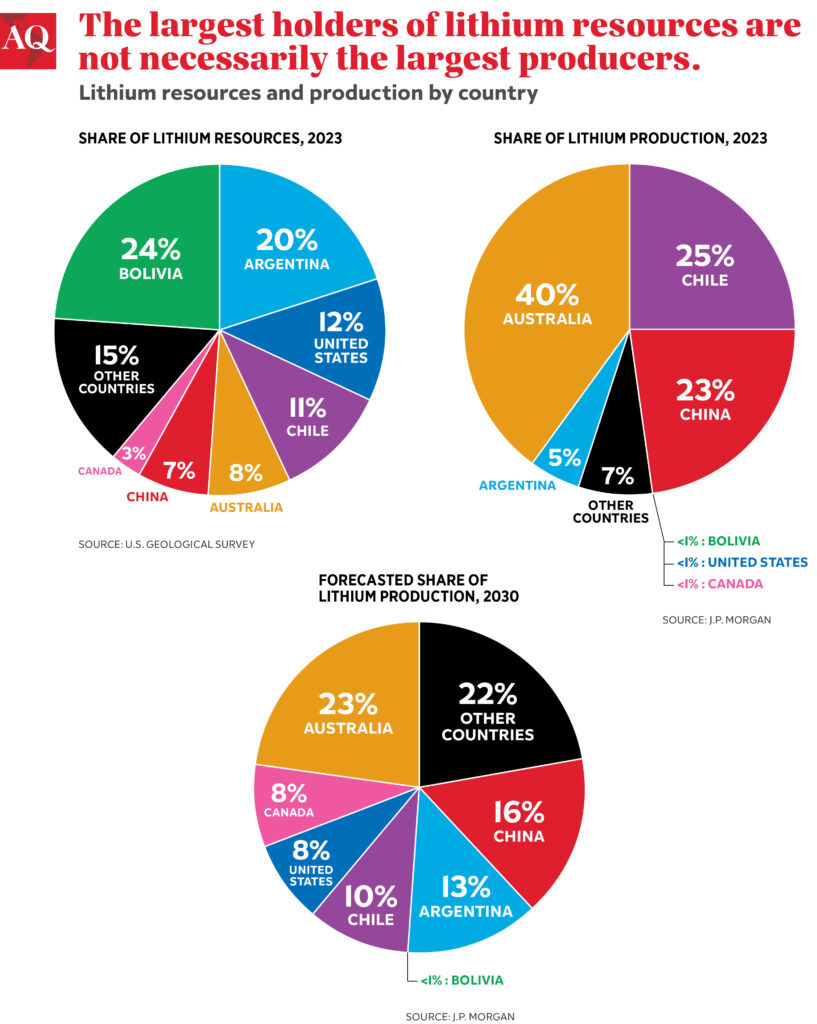

As the world’s second-largest producer of battery-grade lithium carbonate (LCE), a crucial part of electric car batteries, Chile has long outpaced Argentina and Bolivia in attracting investment to mine it. But a series of events is changing Latin America’s so-called “lithium triangle.”

With the world’s largest deposits, Bolivia has secured new multimillion-dollar investments, and Argentina’s lightly regulated lithium sector is roaring full speed ahead. In contrast, Chile has no new projects underway, and a planned overhaul of the industry under President Gabriel Boric, intended to expand state involvement, has yet to be finalized.

And a rapid-moving global competition is hanging over these three players. Production increases in Australia and Brazil, as well as discoveries in the U.S., have heightened pressure to secure new investments in a fast-expanding market. With alternative battery technologies already being developed, Argentina, Bolivia and Chile have a limited window of opportunity to capitalize on the stream of foreign capital heading towards the Andean salt flats before the path of least resistance shifts elsewhere, analysts told AQ.

“There are no new contracts for extraction” that have reached production stages since two existing contracts were finalized in Chile in the late 1970s, Thea Riofrancos, a professor of political science at Providence College, told AQ. Uncertainty surrounding Boric’s lithium strategy hasn’t helped Chile’s growth prospects, as no new investments have been announced since April, and pre-existing contracts remain uncertain. Meanwhile, global LCE demand is expected to increase by 25% annually over the next decade.

As Chile treads water…

That doesn’t necessarily mean Chilean production won’t resume growing after the regulatory framework is finalized. “Investors have wanted to invest in Chile and faced barriers to entry, and this could remove some of those barriers,” Riofrancos said, referring to Chile’s lack of investment in new lithium projects even before the lithium strategy’s announcement.

And don’t count out Chile’s two existing plants: Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile (SQM) and Albemarle, the miners that respectively operate the two plants, are scheduled to increase production in Salar de Atacama between 140,000 to 180,000 tons LCE by 2030, according to Jose Hofer, a former analyst at Chile’s Ministry of Mining and business intelligence manager at SQM. Still, Hofer stressed that the scope of that expansion depends on the results of ongoing contract negotiations between SQM and Codelco, Chile’s state-owned copper company.

…Argentina swims ahead

While many parts of the Argentine economy are seen as domains where government intervention is frequent and heavy-handed—for example, its highly regulated labor market and a bewildering array of exchange rates—when it comes to the decentralized, provincially-regulated lithium sector, it’s a different story.

In contrast to the centralized strategies of Chile and Bolivia, Argentina’s lithium resources belong to the provinces. They—not the federal government—collect a 3% royalty tax for lithium mining (compared to a 40% ceiling in Chile and 45% in Bolivia), and the corporate environment is relatively free of state oversight for foreign mining companies, attracting a diverse array of investors to Jujuy, Salta and Catamarca provinces.

Last year, Argentina produced 33,000 tons of LCE, ranking second in the region and fourth globally. A third mine became operational in June, two other projects are slated for completion next year, and three are under construction. The country has 41 other early-stage projects slated for completion beyond 2025.

According to government data and estimates from miners, Argentina’s national lithium production is projected to increase five-fold by the end of 2025, equating to a boost of around 1% of the current gross domestic product. “Argentina will definitely be capable of bringing capacity above 200,000 tons LCE by 2032-2035,” Hofer said.

Hanging over the future of Argentina’s lithium sector is the societal impact of mining the metal. “The expansion of these lithium plants will surely provoke some kind of displacement or conflict,” said Ernesto Picco, an author and researcher at Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero. Picco noted that “the environmental impact of lithium extraction still hasn’t been fully measured.” Provincial regulation of lithium miners is like “the law of the jungle,” with limited communication channels between corporations and local communities.

Already, a social response is beginning to emerge: for example, in the Tercer Malón de la Paz, a protest that made headlines this August as demonstrators in Buenos Aires demanded enhanced community consultation and a broader commitment to water rights for Indigenous communities in Jujuy province.

What about Bolivia?

Despite possessing the world’s most extensive confirmed lithium resources, Bolivia, the triangle’s third vertex, has so far been incapable of extracting them since the industry was nationalized in 2009—and output reached only 600 tons of LCE last year from a pilot project. However, this dynamic may be changing: Two recently signed projects worth $1.4 billion each, between the state-run Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos (YLB) and Chinese and Russian companies, aim to collectively produce 100,000 tons of LCE per year by the end of 2025 at the massive Uyuni and Coipasa salt flats.

Known for having the most technically complex deposits, lithium projects in Bolivia must overcome spiraling costs, insufficient infrastructure, and a local skilled labor deficit—on top of a new requirement to use a novel technology completely untested at scale.

As such, experts are skeptical. “There’s no way” these projects will meet their production targets, said Chris Berry, founder and president of House Mountain Partners, a consultancy firm. “This is going to take years. I would be surprised if that happened before 2027 or 2029.”

What comes next?

With Chile’s lithium sector stalling and Bolivia’s prospects uncertain, all eyes are on Argentina—and whether its boom brings prosperity and international relevance or social upheaval that derails the industry. Either way, Argentina’s fate will serve as an indicator to other lithium-rich countries in the region with high hopes for the future.

It’s still unclear whether the lithium industry will become part of Latin America’s long history of fraught relationships with an abundance of mineral resources. But it appears that Argentina will have the next chance to write a chapter.

__

Quinn is a new energy reporter at International Business Times UK and a former editorial assistant at AQ