Correction appended below.

Given the way that some in Venezuela and in the international community have been talking about the country lately, you’d be forgiven for thinking that events were shaping up for the country to have a free and fair presidential election in 2024. “Maduro is 100% defeatable,” said Juan Guaidó in January, referring to 2024 election prospects.

Elections in 2024 represent the international consensus solution to Venezuela’s legitimacy crisis. But the fact is that for this to be a truly realistic goal, much more progress should have been made by this point. Nicolás Maduro should have reciprocated the relaxation of U.S. oil sanctions. Details, such as the date for the election, should have started to emerge from Norway-led talks between the opposition and Maduro’s representatives in Mexico City. As part of the humanitarian agreement reached between the sides, frozen Venezuelan funds abroad should be making their way into the country to fight child malnutrition and other aspects of the country’s humanitarian emergency. At the same time, a united opposition front should be organizing their primaries. But sadly, none of this has yet happened.

In fact, in many regards the opposite is taking place. Maduro has not conceded any political space since the U.S. granted a license to Chevron to resume limited energy operations in Venezuela. The talks in Mexico City have bogged down. Negotiations about crucial electoral reforms have not even begun. On top of this, the opposition is mired in one of the most divisive episodes of its history. For there to be a credible presidential election in 2024, 2023 must be the year when the political foundations for it are laid. Today, however, the prospect of such foundations appears far off, even as the country’s crisis persists unabated.

Negotiations between the government and opposition began in August 2022 and have so far yielded a humanitarian agreement to use frozen Venezuelan state funds abroad to pay for the United Nations agencies response to the country’s humanitarian emergency. But the accord is yet to be implemented, and the political portion of the negotiations has not yet started. Though minor reforms were made in time for regional elections in November 2021, much remains to be done in order for a future presidential election to be credible: According to a report by a European Union mission that monitored the regional elections, the last electoral process had severe structural shortcomings, among them the enforcement of laws punishing freedom of expression and voter rolls that undercount voters by a margin of millions.

Maduro, who is facing an investigation by the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity, controls every branch of power in the country, including the Electoral Commission. Electoral reforms depend entirely on him. International pressure and Maduro’s need for recognition can encourage him to follow through, but there are several obstacles that could complicate matters.

The U.S. government has already stated its willingness to re-intensify sanctions if there is no progress on Maduro’s side. “If there isn’t progress in the talks, or [if there’s] regression, we’ll just re-impose the sanctions,” said the White House’s Juan González on the AQ Podcast on January 9. But given changes in the global political and economic landscape, it may be difficult to follow through on ratcheting the pressure back upward.

Subscribe to the Americas Quarterly Podcast on Apple, Spotify, Google and Soundcloud

A new crop of left-wing leaders in Latin America is one part of the equation. Take Colombia, for example: Since taking office, new President Gustavo Petro has prioritized Colombia’s commercial relationship with Venezuela in his foreign policy. And Maduro is a guarantor of peace talks between Bogotá and the ELN—a priority for Petro’s administration—all of which makes firm pressure from Colombia less likely.

At the same time, a global energy crunch has increased the costs of sanctioning Venezuelan oil. President Macron of France, a traditional ally of the Venezuelan opposition (he welcomed Juan Guaidó as interim president to the Élysée Palace in 2020), said in June 2022 Venezuelan oil should enter the market.

Amid weakening international pressure, a still-acute domestic crisis

As real progress remains scarce in Mexico City and the international community’s capacity and willingness to put pressure Maduro falters, the structural challenges that have fueled Venezuela’s twin humanitarian and migration crisis persist.

Take, for example, the country’s continued lack of access to credit. “Credit has disappeared in Venezuela”, the journalist, Omar Lugo wrote in December 2022 in El Estímulo, the newspaper he runs. He is not exaggerating. Owing to Maduro’s lack of international recognition, his government is unable to access much-needed multilateral loans to deal with the country’s collapsing services infrastructure. Nor is he able to restructure the country’s sixty-billion-dollar debt with private creditors, effectively barring Venezuela from the financial markets and from attracting foreign direct investment.

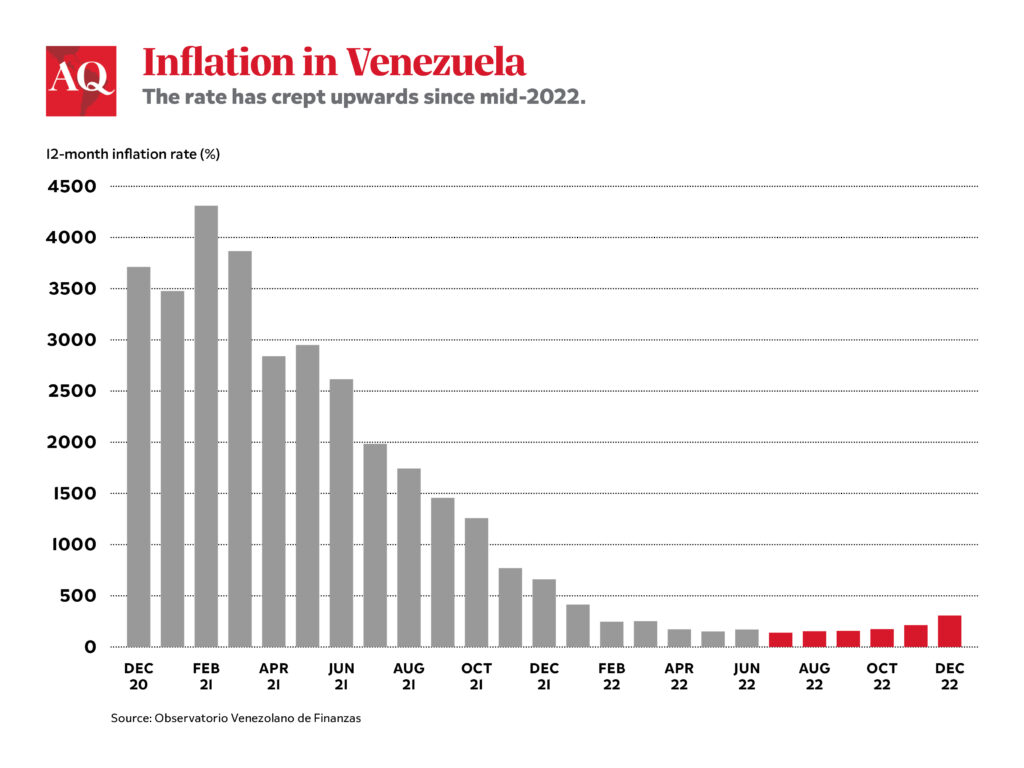

This lack of access to dollars makes it impossible for Maduro’s government to sustain growth in the country’s de facto dollarized economy. A precarious stability achieved in recent years is threatening to give way again. According to several experts’ estimates, last year ended with accumulated inflation close to 300 percent, and there are already talks about a return to hyperinflation, thanks to a rapid appreciation of the U.S. dollar against an increasingly worthless bolívar.

A woeful economic situation should make for fertile political ground for the opposition. But rather than connecting with disenfranchised citizens and channeling dissatisfaction towards an electoral outcome, the leaders of the opposition have been busy accusing each other of treason and corruption after the dissolution of the interim government. One side, led by Juan Guaidó and leaders of his Voluntad Popular party, argues the move was unconstitutional and akin to political suicide—while the other side, led by Julio Borges, a former foreign minister in the interim government, and a collection of other parties, argues it was a necessary move to end a corrupt bureaucracy that lost track of its objective. The decisions that led to the dissolution were reached in Zoom meetings that were not open to the public and never fully explained. This infighting has distracted the opposition leaders from organizing their primaries, for which there are no clear plans yet, and has provided international allies with the perfect excuse for the lack of progress in Mexico City.

Maduro, for his part, has maintained his characteristically repressive rule. More than 100 radio stations (an accessible source of information in a country where internet connections are often poor quality and expensive) were closed last year. There are currently around 240 political prisoners in the country, including elected officials and well-known civil society leaders.

Despite all these challenges, there is still no better opportunity to restore Venezuela’s democracy and legitimacy than the possibility of a presidential election in 2024. But Venezuelans deserve an election that meets international standards, and time is running out to lay the groundwork necessary for an election that meets these standards. Absent serious progress in the near term, Venezuela’s upcoming electoral process will lack credibility, not only for international observers, but for Venezuelan voters, who may refuse to participate in yet another unfree and unfair election. And the stakes are high: A failure to make 2024 elections a success will only deepen one of the worst migration and humanitarian crisis in the region’s history.

This article has been updated to give the correct title of Omar Lugo’s publication.